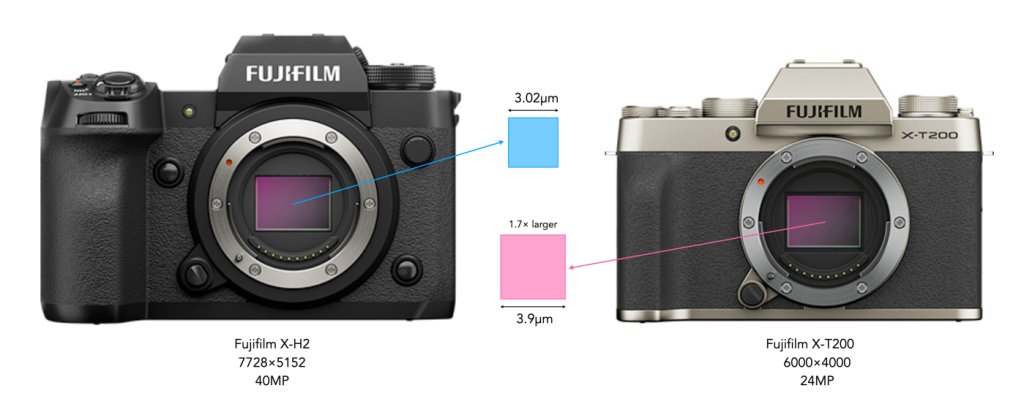

For years we have seen the gradual creep of increased photosites on sensors (images have pixels, sensors have photosites – pixels don’t really have a dimension, whereas photosites do). The question is, how many photosites is too many photosites (within the physical constraints of a sensor)? It doesn’t matter the type of sensor, they have all become more congested – Micro-Four-Thirds has crept up to 25MP (Panasonic DC-GH6), APS-C to 40MP (Fuji X-T5), and full-frame to 60MP (Sony A7R-V).

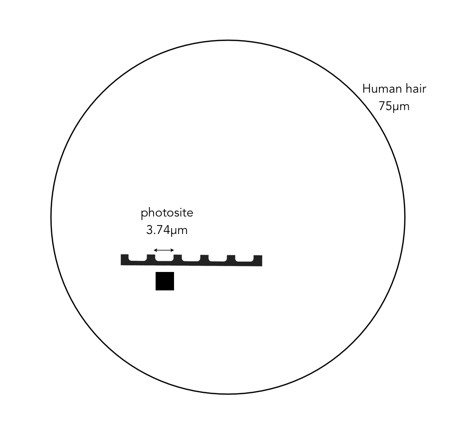

Manufacturers have been cramming more photosites into their sensors for years now, while the sensors themselves haven’t grown any larger. When the first Four Thirds (FT) sensor camera, the Olympus E1, appeared in 2005 it had 2560×1920 photosites (5MP). The latest rendition of the FT sensor, on the 2023 Panasonic Lumix DC-G9 II has 5776×4336 photosites (25MP), on the same sized sensor. So what this means of course is that ultimately photosites get smaller. For example the photosite pitch has changed from 6.89μm to 3μm, which doesn’t seem terrible, until you calculate the area of a photosite: 47.47μm2 to 9μm2, which is quite a disparity (pitch is not really the best indicator when comparing photosites, area is better, because it provides an indication of light gathering area). Yes, its five times more photosites, but each photosite is only 16% the area of the original.

Are smaller photosites a good thing? Many would argue that it doesn’t matter, but at some point there will be some diminishing returns. Part of the problem is the notion that more pixels in an image means better quality. But image quality is an amalgam of many differing things beyond sensor and photosite size including the type of sensor, the file type (JPEG vs. RAW), the photographers knowledge, and above all the quality of a lens. Regardless of how many megapixels there are in an image – if a lens is of poor optical quality, it will nearly always manifest in a lower-quality image.

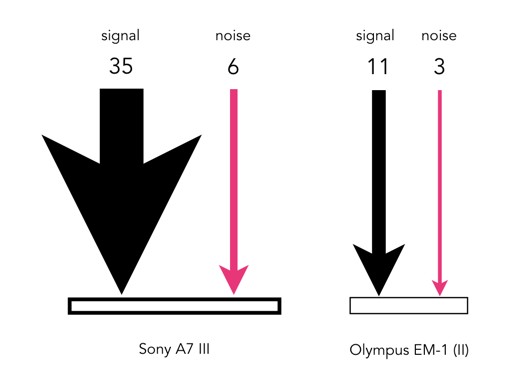

However when something is reduced in size, there are always potential side-effects. Small photosites might be more susceptible to things like noise because despite algorithmic means of noise suppression, it is impossible to eliminate it completely. Larger pixels also collect more light, and as a result are better at averaging out errant information. If you have two different sized sensors with the same amount of photosites, then the larger sensor will arguably deliver better image quality. The question is whether or not photosites are just getting too small on some of these sensors? When will MFT or APS-C reach the point where adding more photosites is counterproductive?

Some manufacturers like Fuji have circumvented this issue by introducing new larger sensor medium format cameras like the GFX 50S II (44×33mm, 51MP) which has a photosite size of 5.3µm – more resolution, but not at the expense of photosite size. Larger sensors typically have larger photosites, resulting in more light being captured and a better dynamic range. These cameras and their lenses are obviously more expensive, but they are designed for people that need high resolution images. The reality is that the average photographer doesn’t need sensors with more photosites – the images produced are just too large and unwieldy for most applications.

The reality is, that cramming more photosites into any of these sensors does not really make any sense. It is possible that the pixel increase is just a smokescreen for the fact that there is little else in the way of camera/sensor innovations. I mean there are the stacked sensors, but their development has been slow – the Foveon X3 has shown little use beyond those found in Sigma cameras (they haven’t really taken off, probably due in part to the cost). Other stacked CMOS sensors are in development, but again it is slow. So to keep people buying cameras, companies need to cram in more photosites, i.e. more megapixels. Other things haven’t changed much either, I mean aperture is aperture right? For example autofocus algorithms haven’t taken a major step forward, and the usability hasn’t done much of anything (except perhaps catering to video shooters). Let’s face it, the race for megapixels is over. Like really over. Yet every new generation of cameras seems to increase the number slightly.