If you look at a advertising from a modern lens manufacturer you will notice that most lenses have offer a lens diagram outlining what the internal design of the lens is, and whether there are special lens elements in it. For most people what’s inside a lens is of little interest, as long as the lens does what it’s suppose to do, however it is a little interesting only because many modern lenses are quite complex inside. What often separates modern digital lenses from vintage film ones is the internal mechanics. While film lenses, and some less-expensive digital lenses had mechanical means of focusing, digital lenses are often auto-focusing, requiring small motors to drive the focusing mechanism. Some manufacturers also produce lenses that have image stabilization mechanisms inside. So there can be a lot going on inside a lens beyond the optical system.

So what features are associated with a modern lens? There are two types of modern digital lens per se. One is bristling with electronics, to deal with apertures, focusing and perhaps stabilization; the other is manual, in such that both focusing and aperture control and done by hand. Why manual? Because it allows lenses to be made in an expensive manner. Fully coupling a lens to a digital camera, which requires electronics, is an expensive venture.

First are the things that have always been on the outside of a lens, namely the aperture ring and focus ring. Now it should be mentioned that some lens makers, e.g. Sigma, produce lenses that are only auto-focus, and as such they don’t offer any sort of manual focus, because there is no focus ring and no ‘manual/auto’ switch. In addition to these are a bunch of features on the outside of a lens that won’t exist on analog lenses. These are usually features specific lens manufacturers have decided would be good for users.

- focus range limiter (Sony) − saves time by limiting the focusing range, some are user specified range.

- aperture click switch (Sony) − allows the aperture ring clicks to be engaged or not (smooth)

- aperture/iris lock (Sony) − prevents unwanted exposure changes while shooting.

- zoom rotation selection switch (Sony) − change zoom direction to match user preferences.

- focus mode (Sony, Sigma) − switch between manual and auto focus

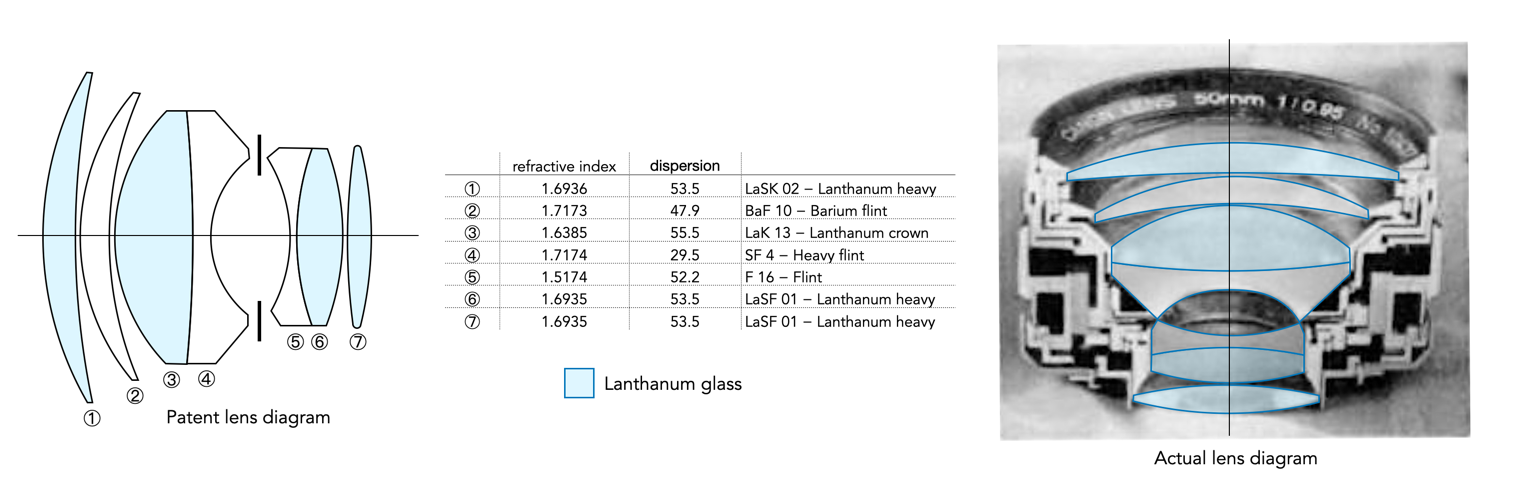

The next component, and perhaps one of the more interesting is the characteristics of the internal lens elements. Lens element diagrams have been a staple of lens brochures since the 1930s. They illustrate the shape of the lens elements, and how they are positioned inside the lens. The difference between digital and analog lenses is that it was very rare to describe the type of glass used for specific elements in vintage lenses. Now things are different. I honestly don’t know why the glass functionality has become so interesting for manufacturers to include, but there you have it.

Consider Figure 2, which shows the elements inside a Sigma 35mm f/1.4 DG DN lens. The diagram highlights four different types of glass lenses: one type is the aspherical (2 elements), and the remaining types are various forms of low dispersion lens (4 lenses in total). This can be a bit bewildering to the average user − what is the difference between “F” low (FLD), extraordinary low (ELD), and special low dispersion (SLD) glass? It’s almost like worrying about the physics behind an SLR sensor. Oh, by the way, FLD means the glass has optical characteristics that mimic flourite (which is low dispersion).

Every manufacturer has its own potpourri of element glass types, it isn’t only restricted to low dispersion. For example Sony’s lenses use the XA Extreme Aspherical (XA) for high resolution and bokeh; Advanced Aspherical Lens (AA) and ED Aspherical Lens (ED Aspherical) made from Extra-Low Dispersion glass.

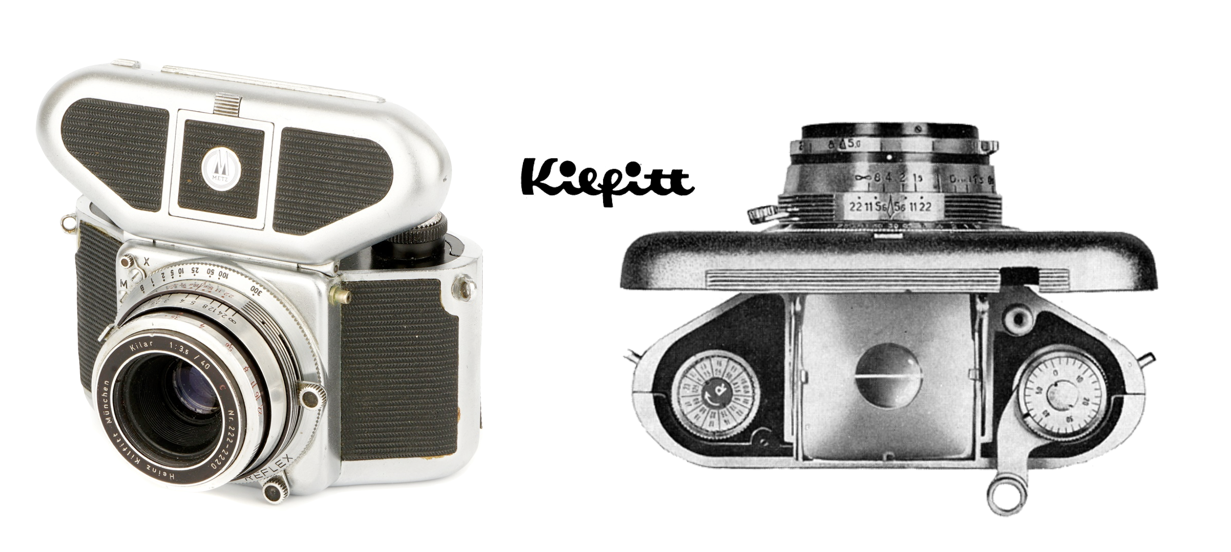

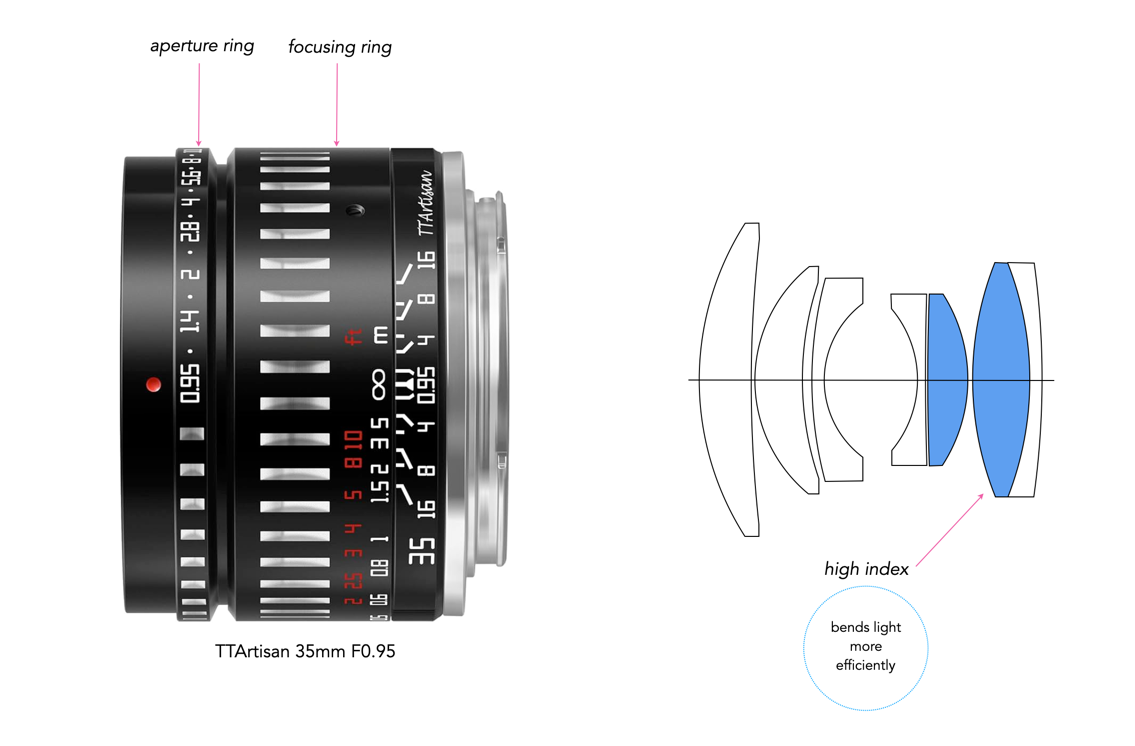

The simpler digital lens designs (and also the cheapest) are those that are manual, and really aren’t that different from their predecessors externally, except for perhaps interesting aesthetics. Internally there are no motors, but they often still have lens diagrams associated with them, albeit simpler, as they are simpler lenses. Consider the TTArtisans 35mm f/0.95 shown in Figure 3. The style of the outside somewhat mimics the “striped” German lenses of the 1960s. The only external artifacts are the aperture and focusing ring. Internally, the lens has two ‘high index’ lenses, to allow for the fast f/0.95 aperture.

There is also some interest in the type of motor driving the focusing mechanism. Why this is important I don’t really know. The Sigma lens above has a ‘Hyper-Sonic Motor’ (HSM), which is just a piezoelectric motor powered by ultrasonic vibrations (note not hypersonic, as in super fast). Every manufacturer has their own name for this. Canon calls it Ultrasonic Motor (USM), and Nikon Silent Wave Motor (SWM).

Finally some lenses also have built-in image stabilization, based on some form of optical stabilization. The technology uses internal gyro sensors to detect camera shake (pitch & yaw) and shifts lens elements in real-time to counteract it. Each manufacturer has their own name for Fuji OIS (Optical Image Stabilization), e.g. Sigma OS (Optical Stabilization), Tamron VC (Vibration Compensation), Sony OSS (Optical SteadyShot), Nikon VR (Vibration Reduction).

There is a lot of technology in a modern digital lens, but we shouldn’t let the tech overwhelm the aesthetic characteristics of a lens, because the image it helps produce is what really counts.

P.S. I will be covering the basics of aspherical and low-dispersion lenses in a future post.