Descriptions of camera gear, regardless of the website aren’t always as truthful as they could be. People use a number of terms to mask the true condition of an item. Some unfortunately do it not knowing any better, perhaps because they don’t sell many cameras or lenses. As usual, stick with sellers that have good feedback, and test the things they sell. A listing that doesn’t really describe the functionality of the lens or camera is one to be avoided, even if it does seem inexpensive (unless it is so cheap you are willing to spin the wheel). Beware that sometimes terms are used to gloss over the fact that there are issues. For instance with lenses sometimes the issues with the optics are fully described, but focusing ability, and aperture control are ignored.

Now on to some of the terms used. Note that many of these terms can be quite subjective.

“Mint”

A term used to theoretically describe a camera or lens that is 100% like the day it left the factory, i.e. pristine or unblemished. The reality is that very few cameras or lenses are pristine. Sometimes the term is used in a roundabout way to describe the cosmetic appearance of a camera or lens with little regard to functionality. Does not guarantee a camera functions, or has even been tested. (See previous post)

“Near mint”

A term used to describe a camera or lens that is close to mint, but not quite. Often used to rate an item in terms of appearance, e.g. minimal scratches, rather than function. Does not guarantee a camera has been tested. Traditionally it describes something that looks as if it was just taken out of the box, or has been handled with extreme care. The definition can be subjective, often causing tension between buyers (expecting perfection) and sellers (who may allow minor defects).

“Minimal traces of use”

This usually implies a camera hasn’t been used that much. But how can one really guarantee how much a 50-year old camera has or hasn’t been used. A camera could look in pristine condition cosmetically, and have been used to take thousands of photos. Unlike a digital camera, there is no way to gauge shutter activations on a film camera.

“Signs of use” / “signs of wear”

Most cameras will show some signs of use. This is a catch-all term used to say that cosmetically it won’t be perfect. Perhaps a few scuffs and scratches, perhaps peeling leatherette, or a bit dirty. It obviously means that camera has been used, and is in fair or good condition. It usually says very little about the condition of the internal components.

“As is”

This means you get it in the state it currently is, with all its faults, known or unknown. It’s a bit superfluous because that’s the same state most things are bought in. Read between the lines and this implies that it has not been tested, and likely has something wrong with it. It’s a catch-all for “buyer-beware”.

“Beautiful”

Terms like beautiful are often used to describe the overall quality of an item, especially with optics. It is such a subjective term that it is pretty meaningless. If describing a lens, then it is better to use terms that relate directly to whether or not it has defects, e.g. the presence of haze, fungus, scratches, dust. I think it is okay when being used to describe a lens whose design is aesthetically pleasing.

“It works properly”

But does it? Unless the camera has been tested using film, it is impossible to say it works properly. A cursory review of a camera may determine that things “work”, but are the shutter speeds accurate? Does the shutter work properly? Are there any light leaks? The same with lenses, which can be tested easily by attaching to a mirrorless system and actually taking photos.

“CLA’d” / “overhauled”

Supposedly the camera/lens has been serviced, CLA means “Clean, lube and adjust”. It is a comprehensive maintenance service performed on cameras (and lenses) to restore them to proper working order. Often there is very little evidence of this, e.g. a description of what was actually performed during the service. If the camera/lens seems too cheap this is a red flag, because a CLA can cost C$150-400.

“Rare”

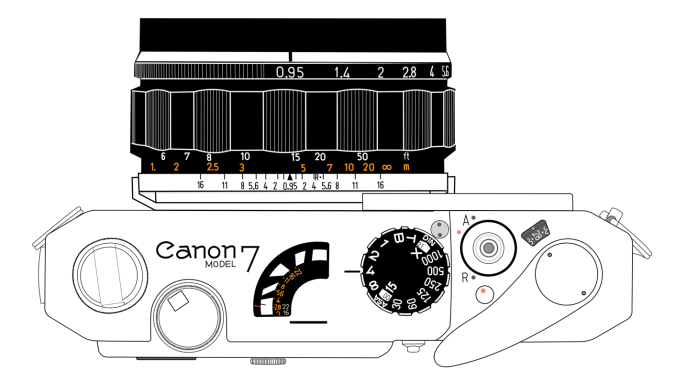

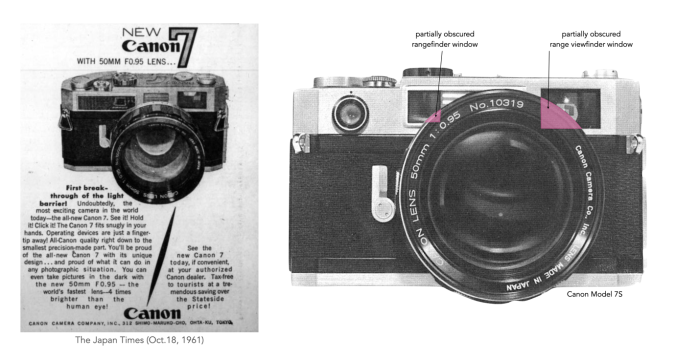

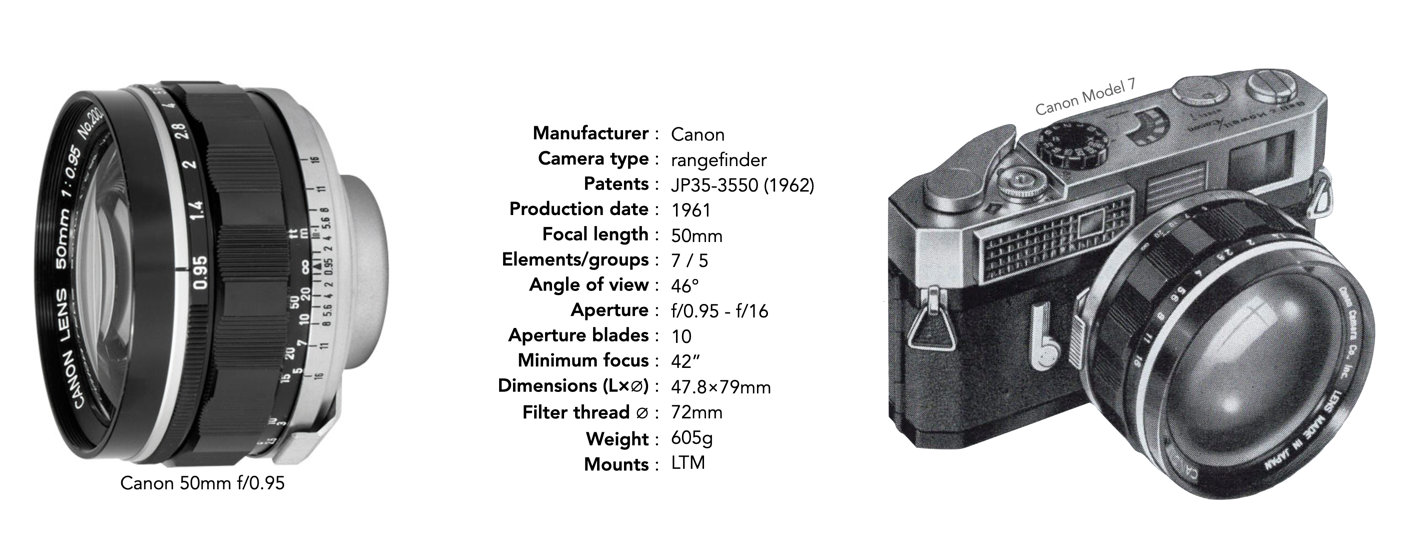

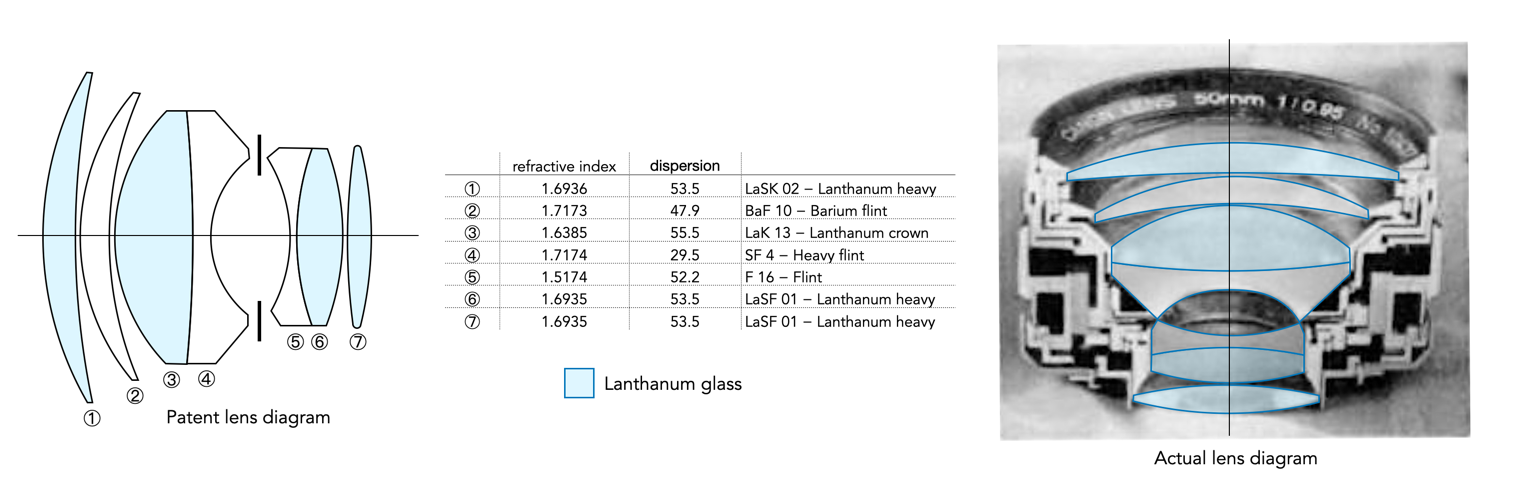

When something is “rare” it means there are very few of them, or at least very few for sale. The term is a quite overused in the photographic realm. For example the Canon “dream” lens, the 50mm f/0.95 could be considered somewhat uncommon, because only 20,000 were produced in comparison to some (a more common lenses may have had a few hundred thousand produced). Yet they are sometimes marked as “rare” which they are not, there are a lot for sale − what they are is expensive, but expensive does not necessarily equal rare. The Meyer Optik Domiron 50mm f/2 on the other hand is a rare lens − produced for about 6 months and prized for its “swirly bokeh”.

“Not tested”

This may be code for defective. Cosmetically the camera may look fine, however functionality has not been investigated at all. Buy at your own risk. It could be a hidden gem for a good price, or something that sits on a shelf.

“For parts” / “repair”

Exactly as it presents, “for parts” means that the item has some sort of defect that prevents its use. Basically another code for defective. For a camera this might mean a defective shutter, for a lens an aperture mechanism that is stuck. It of course can be used as a donor camera to fix a camera. As very few people are likely to use it for parts, except perhaps easy to access external things, these are bought to sit on a shelf, or pull-apart for fun.

Exaggerated ratings

There a certain places which tend to exaggerate ratings, and use the term “mint”, and “near mint” a lot. There is no standardization in ratings, and some are verging on ridiculous. One I have seen had the following system for appearance: brand new (100%), like new (99%), top-mint (97-98%), mint (95-96%), near mint (93-94%), excellent (91-92%), very good (89-90%), and “for parts” (80-85%). There are also some with ratings such as Exc+ to Exc+++++, implying five levels of excellent between “near mint” and “for parts”, which is also ridiculous.

The terms used to describe a lens or camera are only good if used in context. I guess we can be somewhat lucky that people don’t use the terms “epic”, or “mythical” in their descriptions. However some people do use the term “legendary” which I think is okay to use with lenses, but only if they are truly legendary. What does a good condition description look like? Here is one for a Praktina IIa:

“Good overall condition. Some signs of wear are present. The shutter fires, but the speeds do not appear to be accurate. The shutter curtain coating is cracked and no longer light-tight. The lens’s aperture and focus rings function correctly. The lens is free of scratches, delamination, and fungus. There is some haze inside the lens. Bayonet mount lens (specifically for Praktina cameras).”