Sometimes we view a poster or picture from afar and are amazed at the level of detail, or the crispness of the features, yet viewed from up close this just isn’t the case. Is this a trick of the eye? It has to do with the resolving power of the eye.

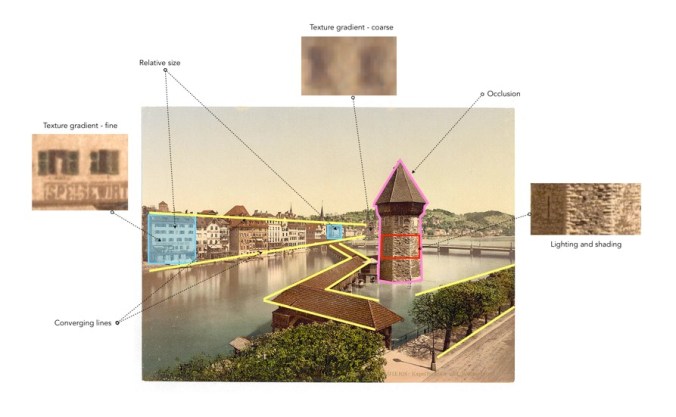

Images, whether they are analog photographs, digital prints, or paintings, can contain many different things. There are geometric patterns, shapes, colours – everything needed in order to perceive the contents of the image (or in the case of some abstract art, not perceive it). Now as we have mentioned before, the sharpest resolution in the human eye occurs in the fovea, which represents about 1% of the eyes visual field – not exactly a lot. The rest of the visual field until the peripheral vision has progressively less ability to discern sharpness. Of course the human visual system does form a picture, because the brain is able to use visual memory to form a mental model of the world as you move around.

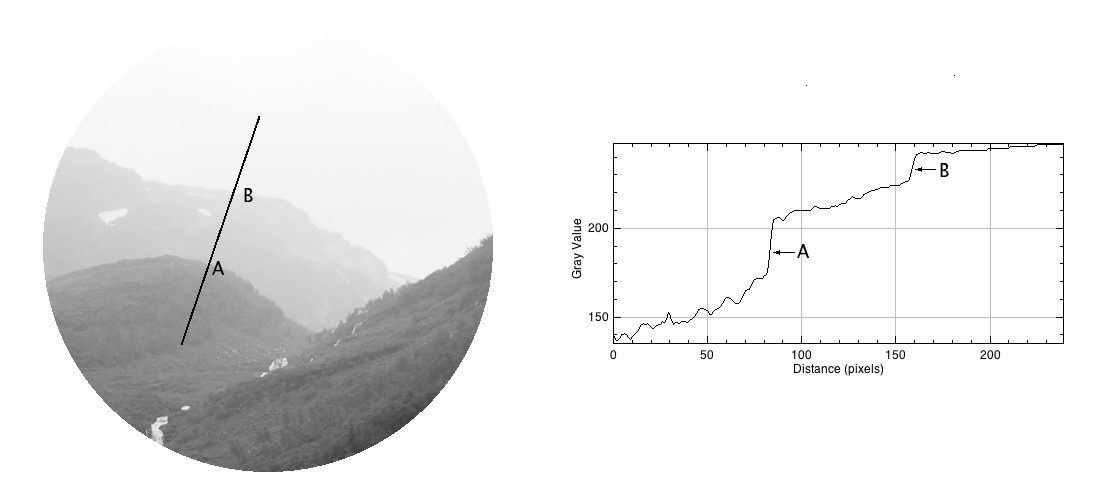

Image resolution plays a role in our perception of images. The human eye is only able to resolve a certain amount of resolution based on viewing distance. There is actually an equation used to calculate this: 2/(0.000291×distance(inches)). A normal human eye (i.e. 20-20 vision) can distinguish patterns of alternating black and white lines with a feature size as small as one minute of an arc, i.e. 1/60 degree or π/(60*180) = 0.000291 radians.

So if a poster were viewed from a distance of 6 feet, the resolution capable of being resolved by the eye is 95 PPI. That’s why the poster in Fig.1, comprised of various separate photographs stitched together (digitally) to form a large image, appears crisp from that distance. It could be printed at 100 DPI, and still look good from that distance. Up close though it is a different story, as many of the edge features are quiet soft, and lack the sharpness expected from the “distant” viewing. The reality it that the poster could be printed at 300 DPI, but viewed from the same distance of 6 feet, it is unlikely the human eye could discern any more detail. It would only be useful if the viewer comes closer, however coming closer then means you may not be able to view the entire scene. Billboards offer another a good example. Billboards are viewed from anywhere from 500-2500 feet away. At 573ft, the human eye can discern 1.0 PPI, at 2500ft it would be 0.23 PPI (it would take 16 in2 to represent 1 pixel). So the images used for billboards don’t need to have a very high resolution.

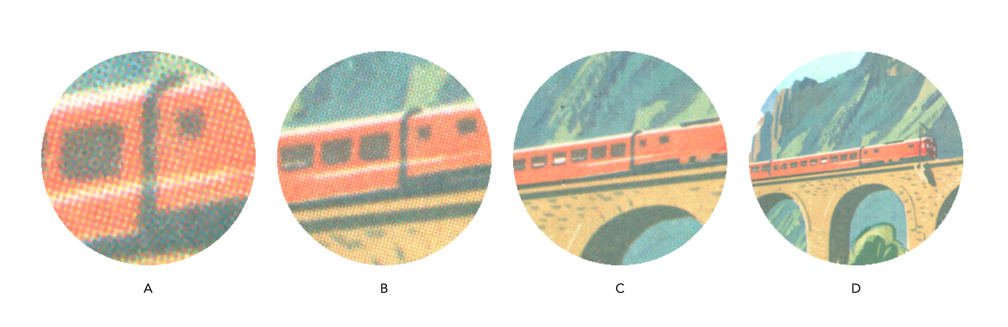

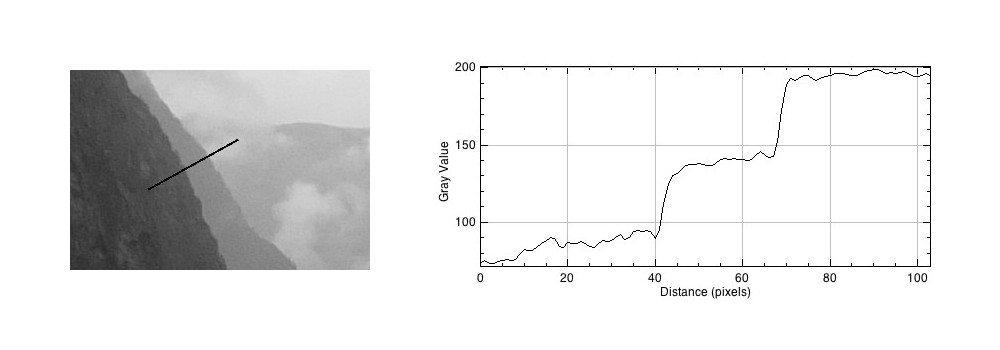

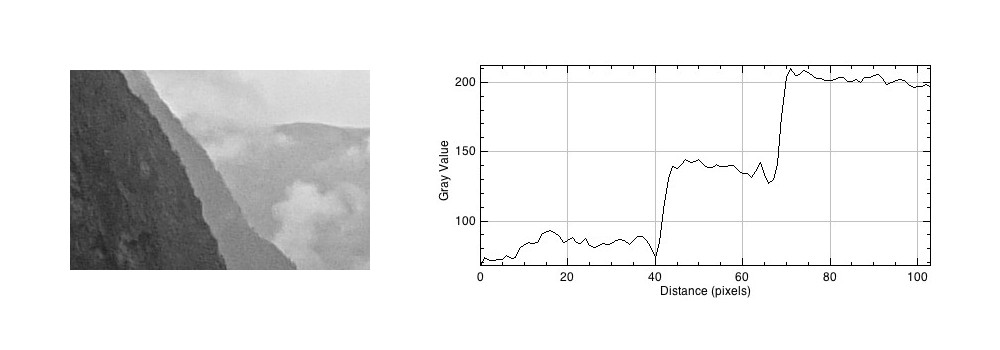

Human perception is then linked to the resolving power of the eye. Resolving power is the ability of the eye to distinguish between very small objects that are very close together. To illustrate this further, consider the images shown in Fig.3. They have been extracted from a digital scan of a vintage brochure taken at various enlargement scales. When viewing the brochure it is impossible to see the dots associated with the printing process, because they are too small to discern (and that’s the point). The original, viewed on the screen is shown in Fig.3D. Even in Fig.3C it is challenging to see the dot pattern that makes up the print. In both Fig.3A and 3B, the dot pattern can be identified. It is no different with any picture. But looking at the picture close up, the perception of the picture is one of blocky, dot matrix, not the continuous image which exists when viewed from afar.

Note that this is an exaggerated example, as the human eye does not have the discerning power to view the dots of the printing process without assistance. If the image were blown up to poster size however, a viewer would be able to discern the printing pattern. Many vintage photographs, such as the vacation pictures sold in 10-12 photo sets work on the same principle. When provided as a 9cm×6cm black-and-white photograph, they seem to show good detail when viewed from 16-24 inches away. However when viewed through a magnifying glass, or enlarged post-digitization, they lack the same sharpness as viewed from afar.

Note that 20-20 vision is based on the 20ft distance from the patient to the acuity chart when taking an eye exam. Outside of North America, the distance is normally 6 metres, and so 20-20 = 6-6.