Everything in modern digital photography seems to hark back to analogue 35mm. The concept of “full-frame” only exists because a full frame sensor is equivalent in size to the 24×36mm frame of 35mm film (which was only called 35mm because that was the width of the film). If we didn’t have this association, there would be no crop-sensor. Most early films for cameras were quite large format – introduced in 1899, 116 format film was 70mm wide. This was followed in 1901 by 120 (60mm), 127 (40mm) in 1912, and then 620 (60mm) in 1931. So there were certainly many film format options. So why did 35mm become the standard?

In all likelihood, 35mm became the gold standard because of how widely available 35mm film was in the motion picture industry – it had been around since 1889 when Thomas Edison’s assistant, William Kennedy Dickson simply split 70mm Eastman Kodak film in half. (I have discussed the origins of 35mm film in a previous post). Kodak introduced the standard 135 film in 1934, and was designed for making static pictures (rather than film) with the actual exposure frames being 36mm wide, and 24mm high, giving it a 3:2 ratio. In the 1930s, Leica brochures expounded the fact that the film used in their cameras was “…the standard 35mm cinema film stock, obtainable all over the world.“

There was much hype in the 1930s about the cameras that were termed “minicams”, or “candid cameras”, in effect cameras that used 35mm film. By the mid 1930s, Leica had been producing 35mm cameras for over a decade. A 1936 Fortune Magazine article titled “The U.S. Minicam Boom” described the Leica as a camera which “took thirty-six pictures the size of the special-delivery stamp on a roll of movie film.” There were those who did not think the miniature camera would survive, seeing their use as a form of candid camera craze. Take for example the closing argument of Thomas Uzzell, who wrote the negative perspective of a 1937 article “Will the Miniature Survive the Candid Camera Craze?” [1]:

“The little German optical jewels you carry in your (sagging) coat pockets make many experimental exposures expensive (though perhaps they would do better if they carefully made one good one!). Their shorter focal lengths make the ultra-fast exposures more practical (how many pictures are actually taken at these ultra speeds!). You can hop about quickly, minnie in hand, and take photos of children and babies at play with all the detail that “makes a picture pulse with naturalness and life” (though good pictures have never been taken by anyone hoping about). … I claim there is just one thing they cannot do, and apparently are never going to be able to do. They can’t make clear pictures.”

Uzzell claimed the art of the miniature was the art of the fuzzy picture. His challenger, Homer Jensen on the other hand described the inherent merits of 35mm over larger format cameras, namely that one could “…take pictures under the most unfavourable conditions, indoors and outdoors.”. Some people disliked the minicam because it made it too easy to take pictures (like anyone could take pictures).

One of the reasons 35mm was so successful was the small size of the camera itself. Their lightweight nature made them easy to carry, taking up very little room. This made them popular with both causal photographers and professionals such as photojournalists where the use of bulky equipment would be prohibitive. Another reason was the 35mm camera’s ability to work in existing light conditions. This was an affect of having ultra-fast lenses, something the larger format cameras could not practically achieve. The shorter focal lengths of 35mm cameras also allowed for greater depth-of-field at wide lens apertures. The inaugural issue of Popular Photography in 1937 described the advantages of using miniatures to capture fast action [4].

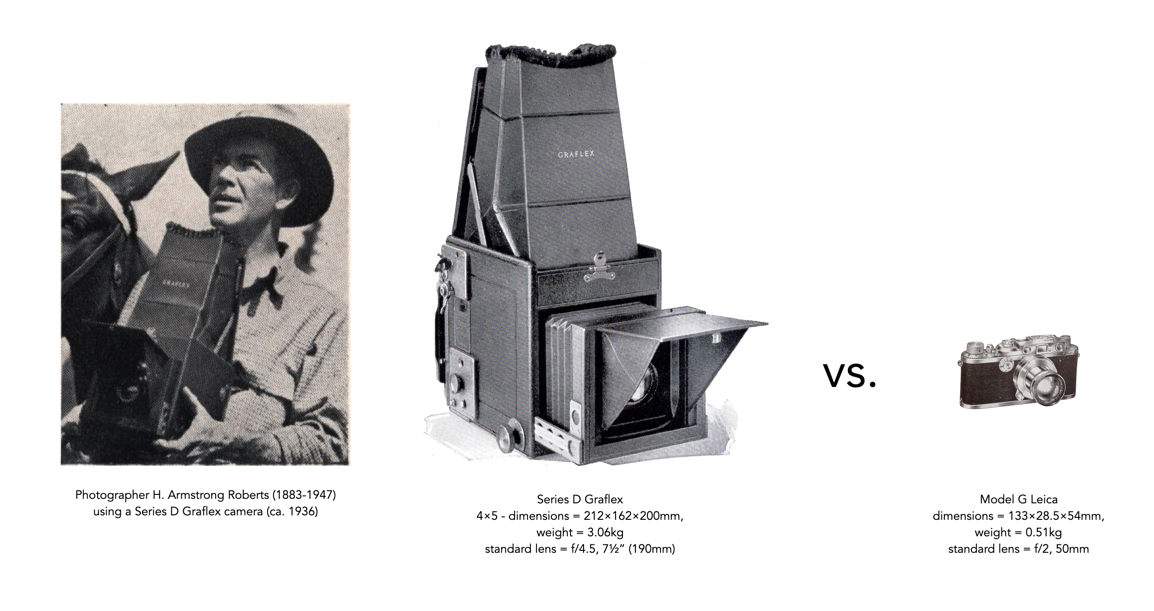

Large format cameras on the other hand, were sometimes referred to as “Big Berthas” due to their size [4]. The Series D Graflex, a quintessential 4×5″ press camera of the 1930s weighed 3.06kg, compared with the Leica G, which was one-sixth its weight, and roughly 1/30th its size. In a Graflex brochure from 1936, photographer H. Armstrong Roberts recalls a recent 14,000 mile journey where he took 3000 negatives using his Graflex camera, stating that “Certain I am that no other camera could have achieved the results which I have obtained with the GRAFLEX.”

In 1935, another event foreshadowed the success of 35mm photography – Kodak’s introduction of Kodachrome colour film, followed shortly afterwards by Agfa’s Agfacolor Neu. This may have persuaded many a professional photographer to move to 35mm. Indeed, by 1938, H. Armstrong Roberts was also shooting in colour using a Zeiss Contaflex with a 50mm f/2 Sonnar lens [5] (so much for his belief in large format). The onset of WW2 brought a halt to the first minicam boom, but it was not the end of the story. By the early 1950s, the minicam was on the cusp of greatness, soon to become the standard means of taking photographs. More articles started to appear in photography magazines, enunciating the virtues of 35mm [3].

There are many reasons 35mm film became the format of choice.

- Kodak’s 135 film single-use cartridge allowed for daylight loading. Prior to this 35mm film had to be loaded onto reusable cassettes in the darkroom.

- The physical format of 35mm film made it very user friendly. The film is contained in a metal canister that reduces the risk of light leaks, and is easy to handle. Loading/unloading film is both intuitive, quick and easy. It’s compact size made it much easier to handle than larger format film.

- 35mm also allowed for more exposures per roll than typical large format films. The norm is 24 or 36 exposures. This provided a great deal of flexibility in the amount of shots that could be taken, because 35mm film was easier and cheaper to develop.

- In the hey-day of film photography there was a huge selection of film types – B&W, colour, infrared, and slide.

Of course there were also some limitations, but these mostly centre on the fact that 35mm film was considered to have less resolving power than medium-format film – great for “snapshots”, but anyone that required large prints needed a large film format to avoid grainy prints.

The invention of the Leica started a new era in photography, spurned on by the introduction of Kodak’s 135 film. Post WW2, 35mm film spearheaded the photographic revolution of the 1950s. It became the format used by amateurs, hobbyists, and professionals alike. 35mm photography allowed for a light, yet flexible kit, which was ideal for the travelling amateur photographer of the 1960s.

Further reading:

- Uzzell, Thomas, H., “Will the Miniature Survive the Candid Camera Craze? – No”, Popular Photography, 1(4), pp. 32,66 (1937)

- Jensen, Homer, “Will the Miniature Survive the Candid Camera Craze? – Yes”, Popular Photography, 1(4), pp. 33,84 (1937)

- “35mm: The camera and how to use it”, Popular Photography, pp.50-54,118, November (1951)

- Witwer, Stan, “Fast Action with a Miniature”, Popular Photography, 1(1) pp.19-20,66 (1937)

- “Taking the May Cover in Color”, Popular Photography, 2(5) pp.54 (1938)