This FAQ covers more of the purchasing aspects of choosing a vintage lens, and is a follow-on to a post I did on buying cameras and lenses.

Is there a price list for vintage lenses somewhere?

Providing generic price information for a genre of lenses is extremely challenging. For example if someone asks what the price of a 50mm lens from manufacture X is, it really depends on a number of different factors: availability (or rarity), the current market, lens quality, speed, and even factors such as the mount type. For example the beloved Carl Zeiss 50mm Planar f/1.4 for a Contax/Yashica mount sells for C$400-600, whereas the same lens with an M42 mount is C$800-1200.

You can find some basic info on camera and lens prices attractive Collectiblend, however not all lenses are listed. There is no one encompassing place to find prices, yet sometimes eBay provides a good cross-section of the current market.

Why are some lenses so expensive?

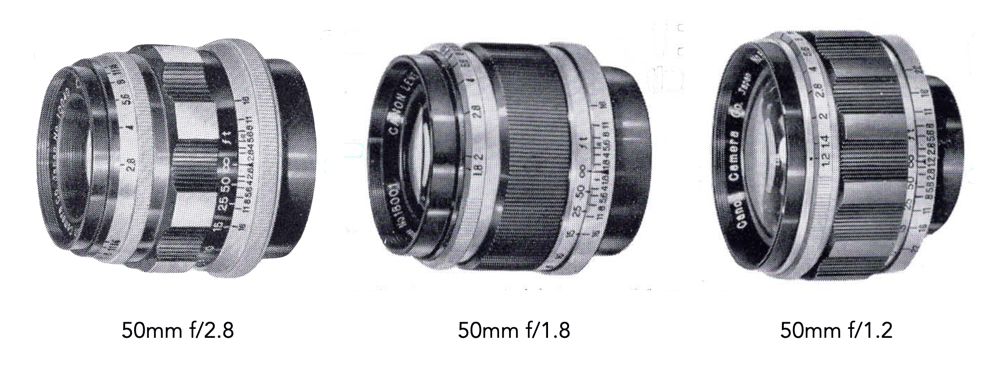

Some lenses are expensive, either because the lens is rare, or has some attribute that makes it more expensive, or a review by someone with a lot of followers has pushed prices up. A good example is wide aperture lenses. If you are looking for a vintage f/1.0 lens, expect to pay a lot of money for it. For example a Leitz 50mm f/1 Noctilux-M lens is C$6-8K. A Canon 50mm f/1.2 rangefinder lens (LTM) will however only cost C$-400-800. Even a Helios 40, 85mm f/1.5 lens will fetch $500, even though it’s only real virtue is that it is considered the “Bokeh King”.

Why is there so much price variability?

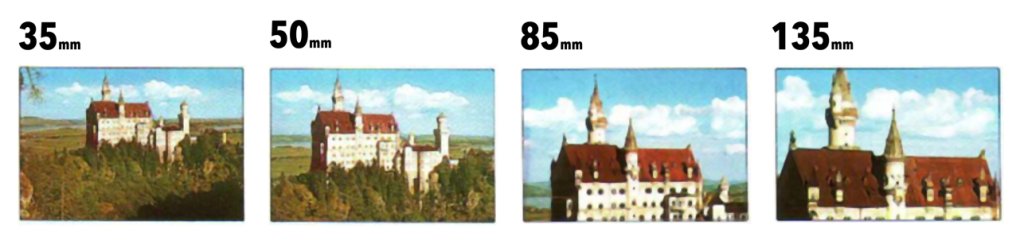

The price of a lens depends on many factors, the same things that afflict super-fast lenses affect all lenses: rarity, quality of optical glass, manufacturer, lens quality, desirability. You will pay less for a 50mm f/2.8 than a f/1.4 and less for a Vivitar lens than a Pentax. Consider the following list of 50mm f/1.8 lenses, and their approximate market prices.

- Vivitar M42 50mm f/1.8 − C$65-80

- Asahi Takumar 50mm f/1.8 − C$80-120

- Carl Zeiss Jena 50mm f/1.8 Pancolar − C$200-400

- Meyer-Optik Görlitz 50mm f/1.8 Oreston − C$150-250

- Carl Zeiss Planar 50mm f/1.8 − C$200-400 (M42 mount C$500-800)

Should I take a risk on a cheap item?

Sometimes there are sellers who are selling a piece of camera gear without knowing what they have, usually because it was part of an estate, and not something they normally deal with. If the item is cheap enough, there is likely very little risk, but if it seems too expensive, avoid it. This is especially true if the item is marked “rare”. A good reseller will mark the item as “untested”, or elaborate on the problems with the lens, e.g. sticky aperture, presence of fungus on the lens.

How do you know a lens will be in good condition?

You don’t, unless you buy from a reputable dealer. Someone who has been dealing in vintage photographic equipement for a long time, and sells a good amount of it will provide a good insight into a particular lens, including providing a quality rating.

If a lens physically looks good, it should be okay right?

Probably, but you just never really know. Unless a lens has some sort of provenance, it’s hard to know where it has spent its life, and what it was used for. Was it used by a photojournalist? Was it ever dropped? It is possible to drop a lens and see no external changes, yet it might cause minor misalignment of some internal working. Was it kept in cupboard in a damp room? So many possibilities. That’s the benefit of buying a lens in-person versus online.

How do I know if a shop is good?

This is tricky, but I suggest searching for reviews on the shop. There are a couple of online stores that have extremely bad ratings. Good shops will have an active social media presence, and often a physical store. The larger the store, the larger the amount, and scope of stock. Smaller stores tend to focus more on specialized or rare cameras/lenses. It pays to do some research.

Are there red-flags for buying lenses online?

Yes – if a listing somewhere only has 1-2 images, and offers no real description, then stay well clear – unless of course it is a $1000 lens selling for $10, and even then you have to wonder what is wrong with it.

Is eBay any good?

Like anything, it really depends on the reseller. Some sell only camera gear, and have been doing it for a while, or have a physical shop and use eBay as their storefront. Always check the resellers ratings, and review comments.

There are a lot of lenses available on eBay from Japan – are they trustworthy?

In most circumstances yes. There are a lot of physical camera stores in Japan, so its no surprise that there are a lot of online stores. Japanese resellers are amongst the best around, because nearly all of them rate every aspect of a lens, cosmetic and functional. If something seems like a bargain it is likely because there are a lot of vintage cameras and lenses in Japan.

What should lens ratings include?

If we take the example of Japanese resellers, there are normally four categories: overall condition, appearance, optics, and functionality. Appearance deals with aesthetics of the lens, and indicates any defects present on the lens body, e.g. scratches or scuffs. Optics deals with the presence of absence of optical issues: haze, fungus, balsam separation, scratches, dust. Finally functionality deals with the operation of the lens, e.g. aperture stiffness.