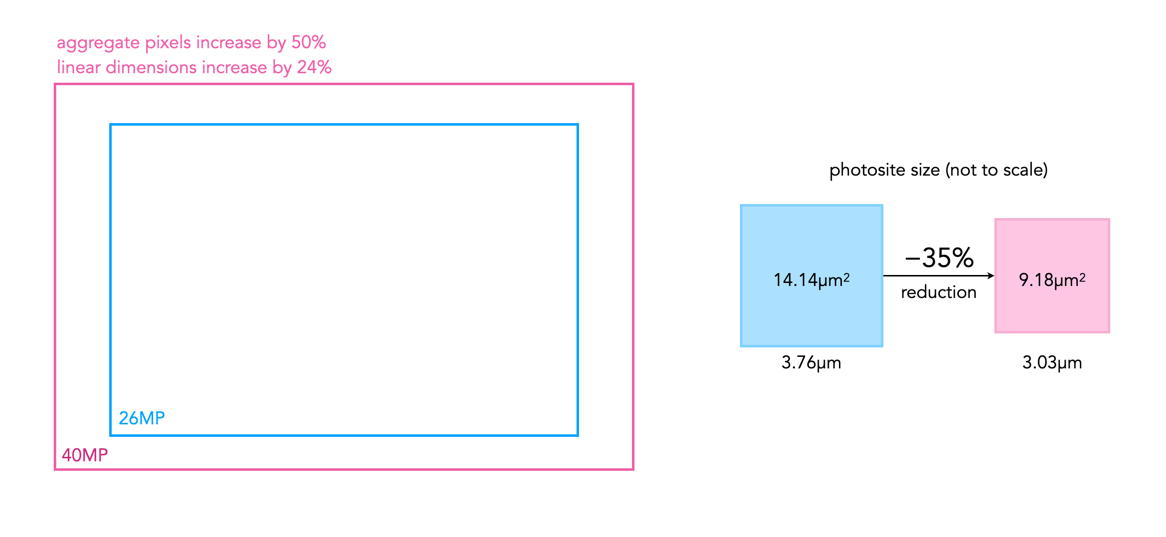

The most obvious choice when it comes to APS-C cameras is usually the number of megapixels. Not that there is really that much to choose from. Usually it is a case of 24/26MP or 40MP. Does the jump to 40MP really make all that much difference? Well, yes and no. To illustrate this we will compare two Fujifilm cameras: (i) the 26MP X-M5 with 6240×4160 photosites, and (ii) the 40MP X-T50 with 7728×5152 photosites.

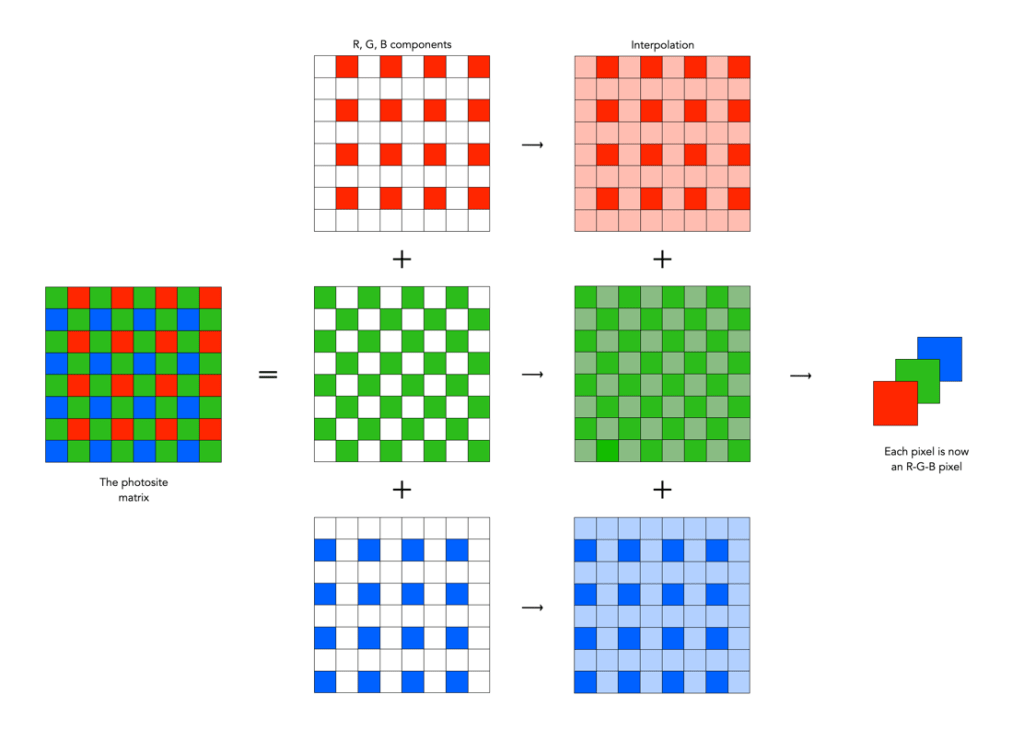

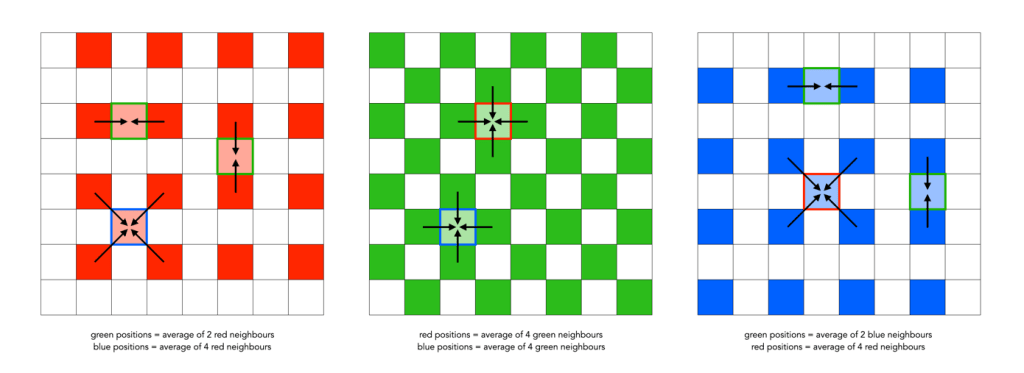

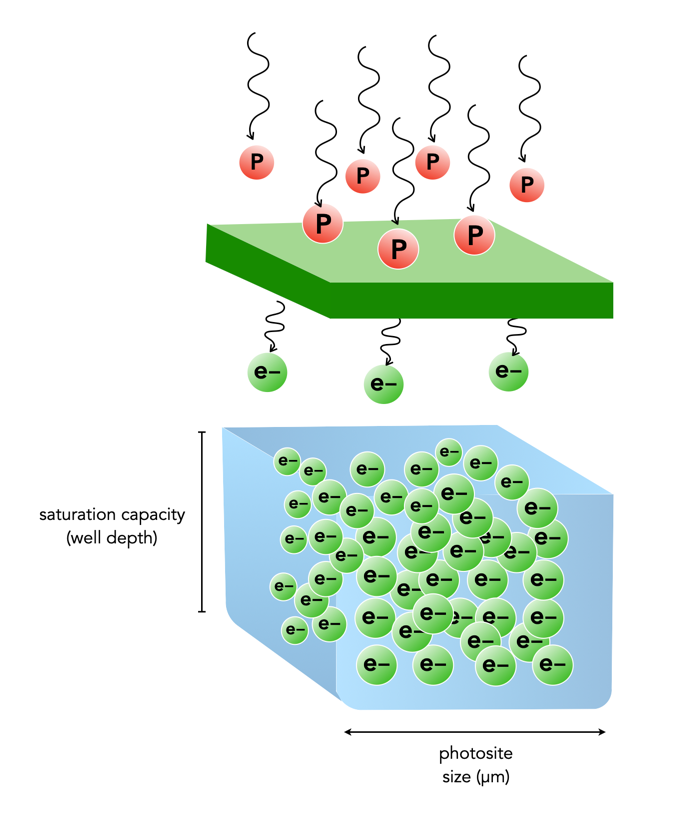

Firstly, an increase in megapixels just means that more photosites have been crammed onto the sensor, and as a result they have been reduced in size (sensor photosites have dimensions, whereas image pixels are dimensionless). The size of the photosites in the X-M5 is 3.76µm, versus 3.03µm for the X-T50. This is a 35% reduction in the area of a photosite on the X-T50 relative to the X-M5, which might or might not be important (it is hard to truly compare photosites given the underlying technologies and number of variables involved).

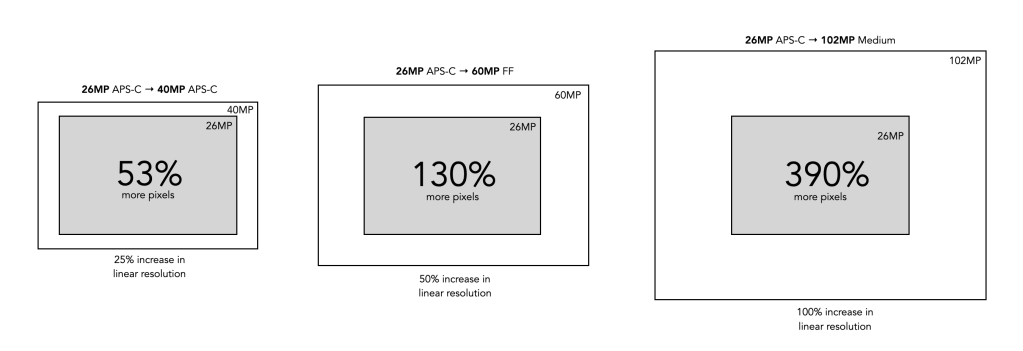

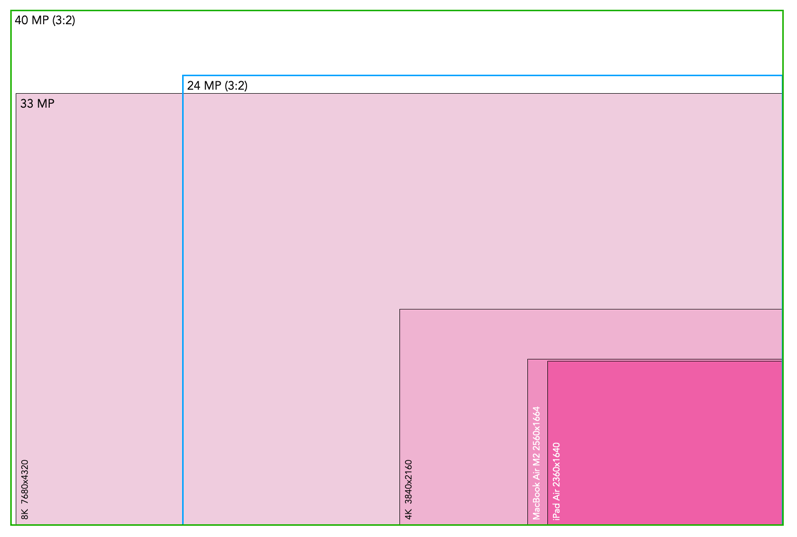

Secondly, from an image perspective, a 40MP sensor will produce an image with more aggregate pixels in it than a 26MP image, 1.5 times more in fact. But aggregate pixels only relate to the total amount of pixels in the resulting image. The other thing to consider is the linear dimensions of an image, which relates to its width and height. Increasing the amount of pixels in an image by 50% does not increase the linear dimensions by 50%. For example doubling the photosites on a sensor will double the aggregate pixels in an image. However to double the linear dimensions of an image, the number of photosites on the sensor need to be quadrupled. So 26MP needs to ramp up to 104MP in order to double the linear dimensions. So the X-T50 will produce an image with 39,814,656 pixels in it, versus 25,958,400 pixels for the X-M5. This relates to 1.53 times as many aggregate pixels. However the linear dimensions only increase 1.24 times, as illustrated in Fig.1.

So is the 40MP camera better than the 26MP camera? It does produce images with slightly more resolution, because there are more photosites on the sensor. But the linear dimensions may not warrant the extra cost in going from 26MP to 40MP (US$800 versus US$1400 for the sample Fuji cameras, body only). The 40MP sensor does allow for a better ability to crop, and marginally more detail. It also allows for the ability to print larger posters. Conversely the images are larger, and take more computational resources to process.

At the end of the day, it’s not about how many image megapixels a camera can produce, it’s more about clarity, composition, and of course the subject matter. Higher megapixels might be important for professional photographers or for people who focus on landscapes, but as amateurs, most of us should be more concerned with capturing the moment rather than getting going down the rabbit hole of pixel count.

Further reading: