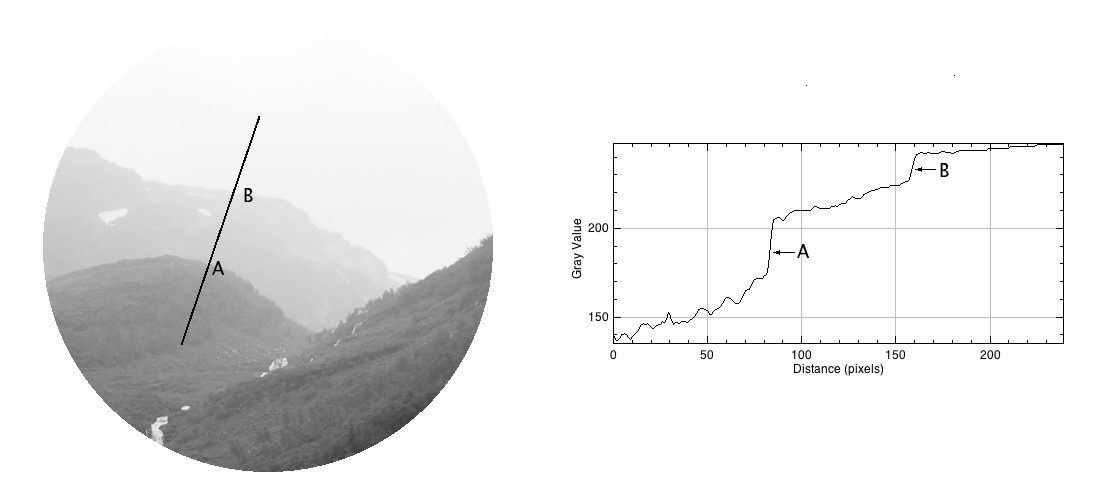

More important than most things in photography is acuity – which is really just a fancy word for sharpness, or even image crispness. Photographs can be blurry for a number of reasons, but usually they are all trumped by lack of proper focusing, which adds a softness to an image. Now in a 3000×4000 pixel image, this blurriness may not be that apparent – and will only manifest itself when an enlargement is made of a section of the image. In terms of photographing landscapes, the overall details in the image may be crisp, however small objects may “seem” blurry, because they are small, and lack detail in any case. Sharpening will also fail to fix large blur artifacts – i.e. it’s not going to remove defocus from a photograph which was not properly focused. It is ideal for making fine details crisper.

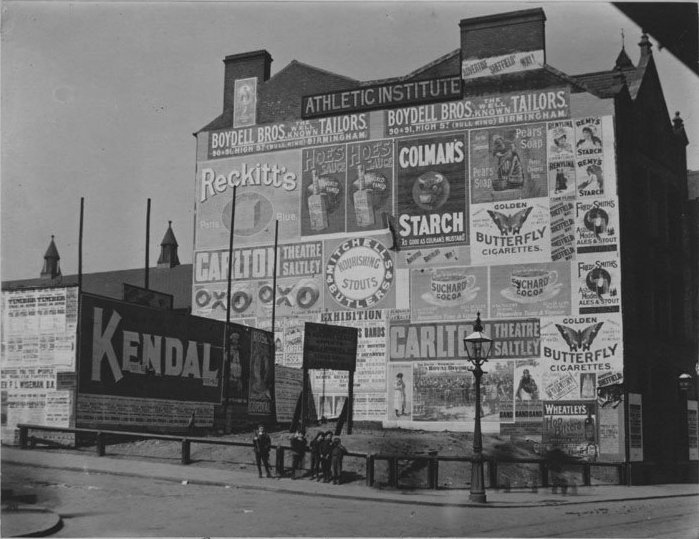

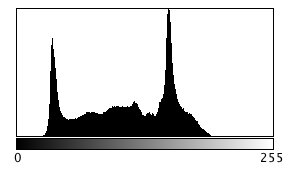

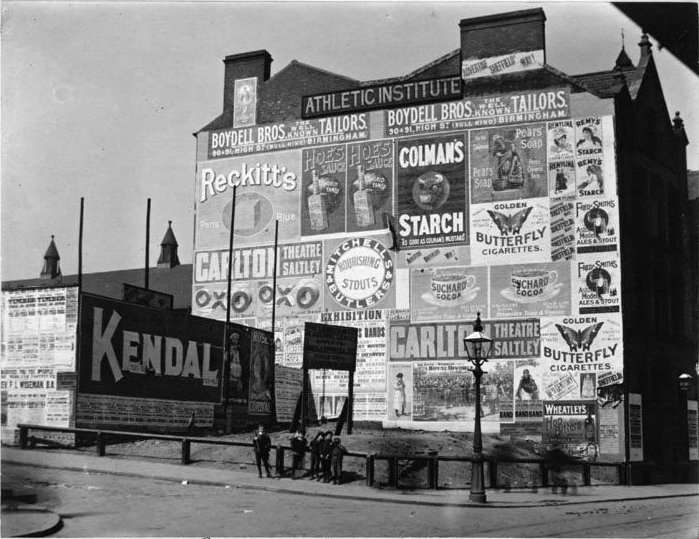

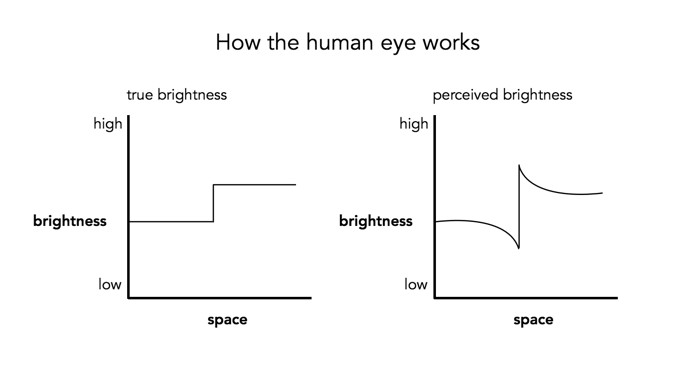

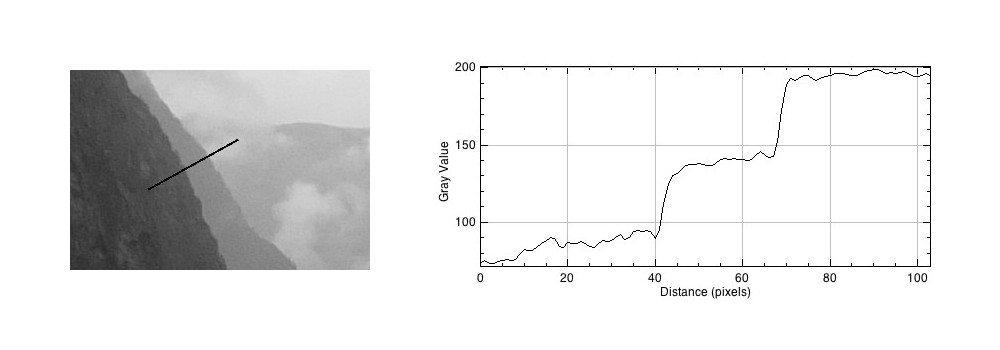

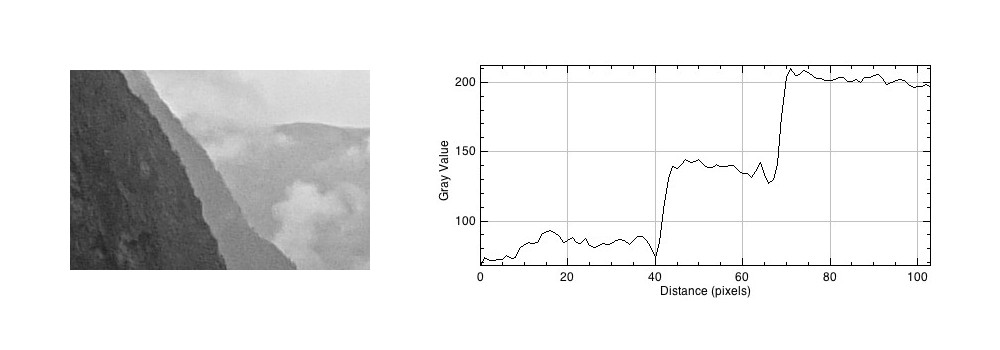

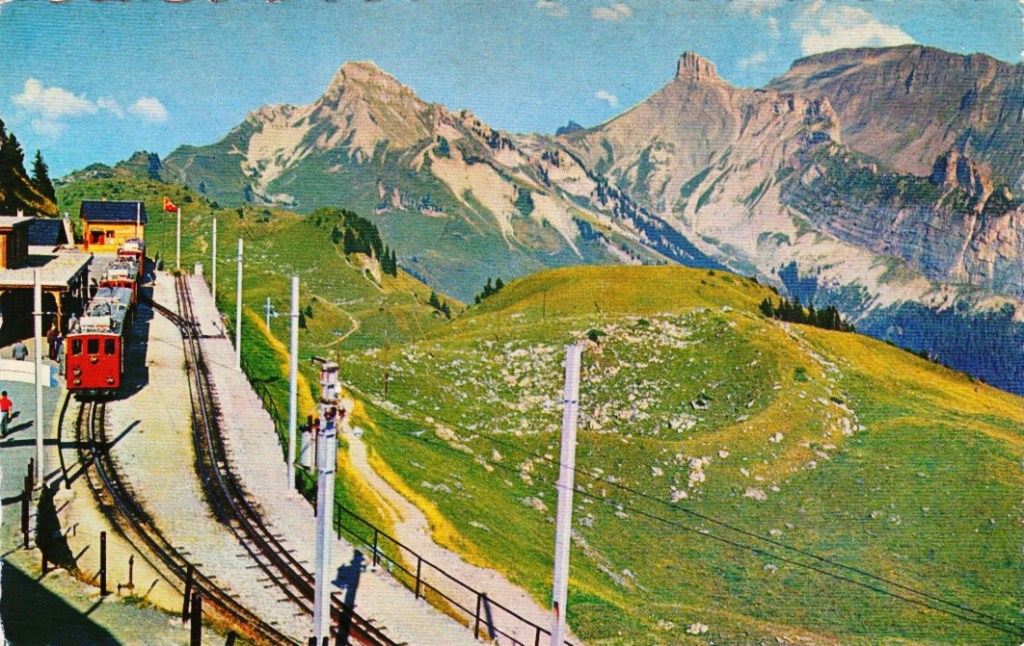

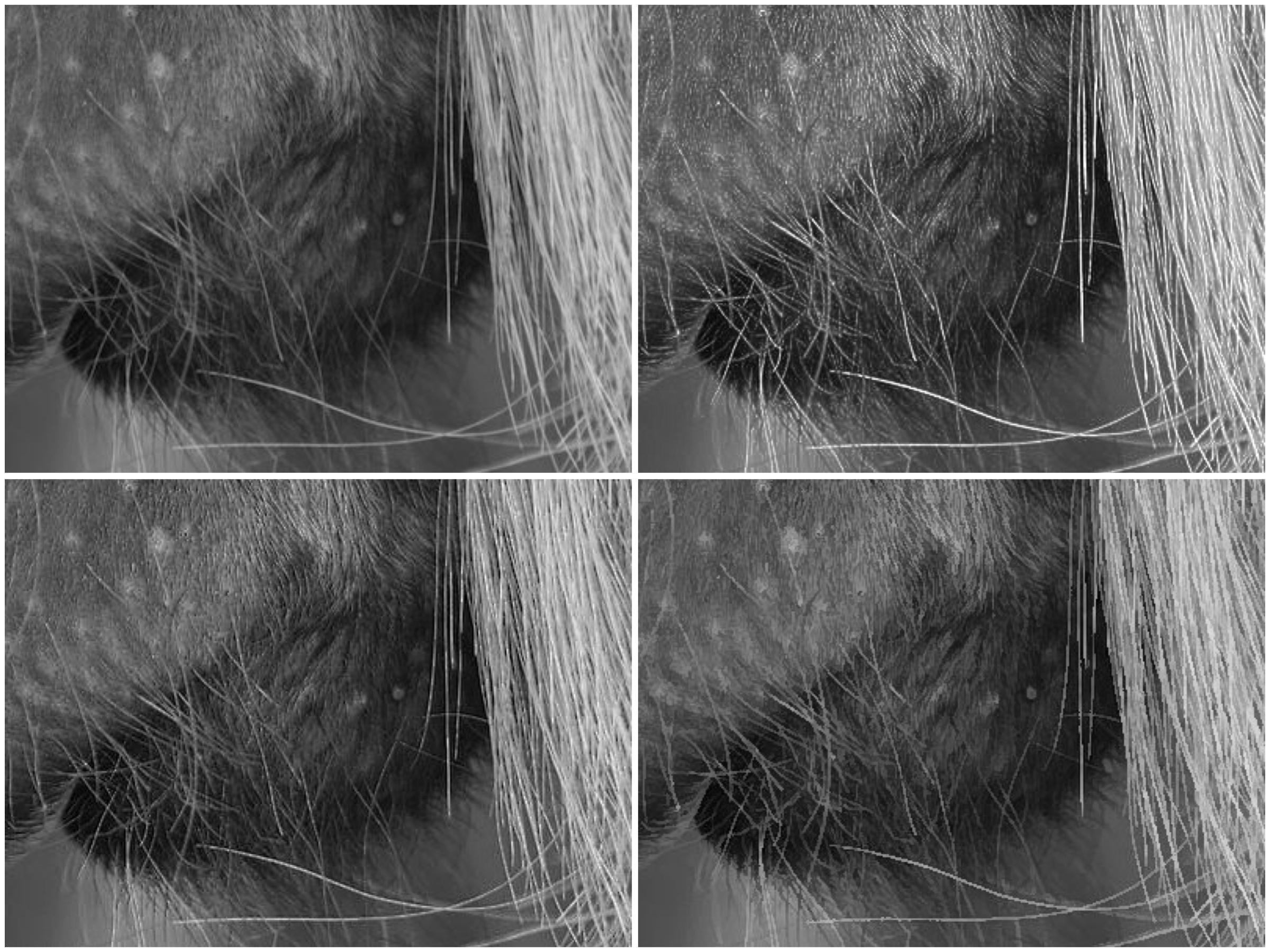

Photo apps and “image editing” software often contains some means of improving the sharpness of images. Usually by means of the “cheapest” algorithm in existence – “unsharp masking”. It works by subtracting a “softened” copy of an image from the original. And by softened, I mean blurred. It basically reduces the lower frequency components of the image. But it is no magical panacea. If there is noise in an image, it too will be attenuated. The benefit of sharpening can often be seen best on images containing fine details. Here are examples of three different types of sharpening algorithms on an image with a lot of fine detail.

Three filters are shown here are (i) Unsharp masking (USM), (ii) Cubic Unsharp masking (CUSM) and (iii) Morphological sharpening (MS). Each of these techniques has its benefits and drawbacks, and the final image with improved acuity can only really be judged through visual assessment. Some algorithms may be more attune to sharpening large nonuniform regions (MS), whilst others (USM, CUSM) may be more aligned with sharpening fine details.