When Carl Zeiss Jena was still under US control in June 1945, the US Army Signal Corp’s Pictorial Division expropriated the “Zeiss lens collection”, which consisted of approximately 2000 sample lenses, and associated documentation. The collection was handed over to Colonel Tebov on May 12, 1945 in Jena.

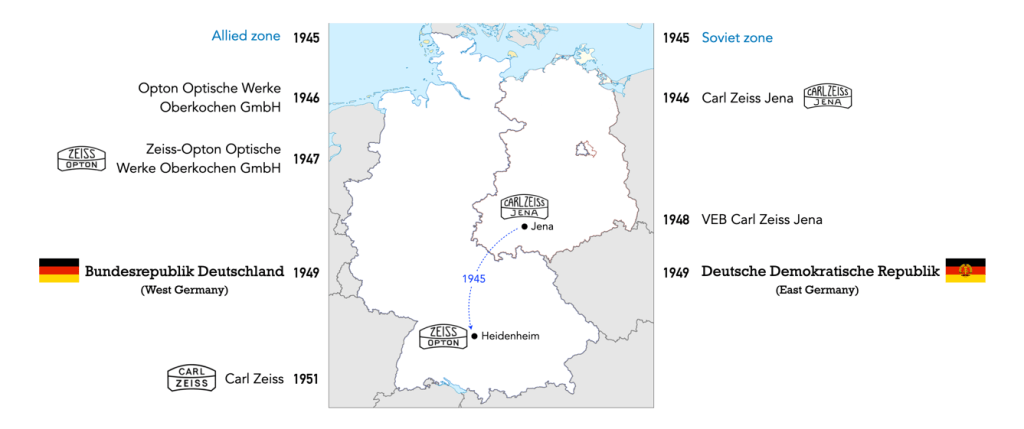

The collection represented not only Zeiss lenses, but optics from other manufacturers, and was used in research and production control. The lenses were transferred to the Signal Corps laboratories at Fort Monmouth, and the documentation to Dayton-Wright Army Air Field in Ohio. At Fort Monmouth, chief of the photographic branch (Signal Corps Engineering Laboratories) Dr. Edward F. Kaprelian, studied the lenses, attempting to understand and recreate the optical designs in many of the prototype Zeiss lenses. Supposedly the lenses were to be analyzed, in particular several hundred experimental lenses that were never sold. None of these historically and technically significant lenses had been clearly documented as part of the appropriation. Willy Merté, head of optical computation at the former Carl Zeiss Jena was apparently languishing in a refugee camp in Heidenheim before Carl Zeiss could begin operation in Western Germany. Merté would go on to catalogue the collection.

In April 1947, Popular Photography was the first major US publication to give a two page sneak peek [1]. Example lenses described include:

- The Spherogon, a 1.9cm f/8 lens with a plano (flat) front element 3” in diameter, with an AOV of almost 160°.

- The R-Biotar, was the fastest commercially produced lens in the world, at 4.5cm with an aperture of f/0.85. It was used for 16mm movies of fluorescent x-ray screens.

- The Bauart BLC, a 20cm f/6.3 objective used by the Luftwaffe for aerial mapping.

- The Perimetar 2.5cm f/6.3 for 35mm cameras, covering a 90° AOV with a deeply concave front element.

Probably the best description of some of the more unusual lenses comes from a June 1947 article by Kaprelian himself [2]. In it he describes some of the V (versuch) or experimental lenses. He describes lenses like the V1940, a 7.5cm f/2.8 lens with a 70° AOV, with little astigmatism or coma, and very little in the way of distortion. Or the V1935, 10cm f/6.2 lens whose front element is strongly concave. Another lens already produced in certain quantities was the Sphaerogon, available in focal lengths from 1.6 to 12cm and f/7, f/8 apertures. Other lenses include experimental aspherical surfaces, telephoto, and wide-aperture lenses.

Where are these lenses today? Perhaps stuck in a storage locker somewhere in the vast storage facilities of the US Army? Well, actually no. In an article in Zeiss Historica in 2016, the fate of the collection is documented [3]. Stefan Baumgartner bought a number of lenses from the collection in 2006, and as he tells it, this is when a major portion of the collection was put up for sale on eBay, a legacy of the estate from American photographic businessman Burleigh Brooks. Apparently after Kaprelian’s release from his military service the collection was left in the custodianship of Burke and James in Chicago, occupying warehouse space for about 20 years. It was later disposed of as military surplus, which is why Brooks probably acquired some of the lenses (as he owned Burke and James).

Further reading:

- Walter Steinhard, “Lens Oddities”, Popular Photography, 20(4), pp.82-83 (1947)

- Edward K. Kaprelian, “Recent and Unusual German Lens Designs”, Journal of the Optical Society of America, 37(6), pp.446-471 (June, 1947)

- Stefan Baumgartner, “A Mystery of Another Lens from the Zeiss Collection”, Zeiss Historica, 38(1), pp.17- (Spring, 2016)