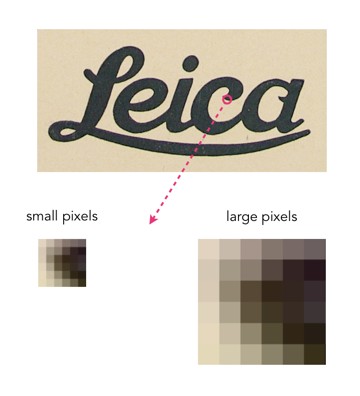

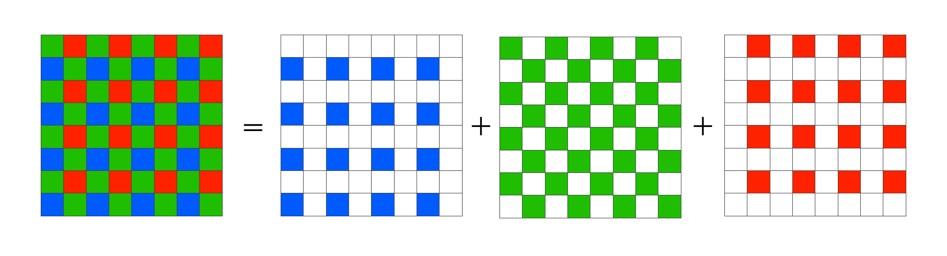

Everyone has some image that they wish had better resolution, i.e. the image would have finer detail. The problem with this concept is that it is almost impossible to create pixels from information that did not exist in the original image. For example if you want to increase the size of an image 4 times, that basically means that a 100×100 pixel image would be transformed into an image 400×400 pixels in size. There is a glitch here though, increasing the dimensions of the image by four times, actually increases the data within the image by 16 times. The original image had 10,000 pixels, yet the new image will have 160,000 pixels. That means 150,000 pixels of information will have to be interpreted from the original 10,000 pixels. That’s a lot of “padding” information that doesn’t exist.

There are a lot of algorithms out there that suggest that they can increase the resolution of an image anywhere from 2-16 times. It is easy to be skeptical about these claims, so do they work? I tested two of these platforms on two vastly different images. Images where I was interested in seeing a higher resolution. The first image is a segment of an B&W aerial photograph of my neighbourhood from 1959. I have always been interested in seeing the finer details, so will super-resolution fix this problem? The second image is a small image of a vintage art poster which I would print were it to have better resolution.

My experiments were performed on two online systems: (i) AI Image Enlarger, and (ii) Deep Image. Now both seem to use AI in some manner to perform the super-resolution. I upscaled both images 4 times (the max of the free settings). Now these experiments are quick-and-dirty, offering inputs from the broadest ends of the spectrum. They are compared to the original image “upscaled” four times using a simple scaling algorithm, i.e. each pixel in the input image becomes 4 pixels in the output image.

The first experiment with the B&W aerial photograph (490×503) increased the size of the image to 1960×2092 pixels. Neither super-resolution algorithm produced any results which are perceptually different from the original, i.e. there is no perceived enhanced resolution. This works to the theory of “garbage-in, garbage-out”, i.e. you cannot make information from nothing. Photographs are inherently harder to upsize than other forms of image.

The next experiment with the coloured poster (318×509) increased the size of the image to 1272×2036 pixels. Here the results from both algorithms are quite good. Both algorithms enhance detail within the images, making things more crisp, aesthetically pleasing, and actually increasing the detail resolution. Why did the poster turn out better? This is mainly because artwork contains a lot more distinct edges between objects, and the colour also likely contributes to the algorithms success.

To compare the algorithms, I have extracted two segments from the poster image, to show how the differing algorithms deal with the super-resolution. The AI Image Enlarger seems to retain more details, while producing a softer look, whereas Deep Image enhances some details (river flow) at the expense of others, some of which it almost erodes (bridge structure, locomotive windows).

The other big difference is that AI Image Enlarger was relatively fast, whereas Deep Image was as slow as molasses. The overall conclusion? I think super-resolution algorithms work fine for tasks that have a good amount of contrast in them, and possibly images with distinct transitions, such as artwork. However trying to get details out of images with indistinct objects in them is not going to work too well.