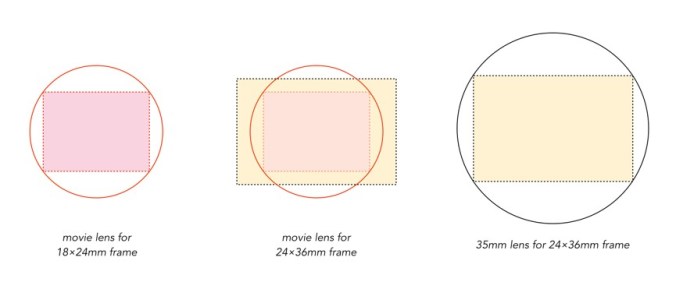

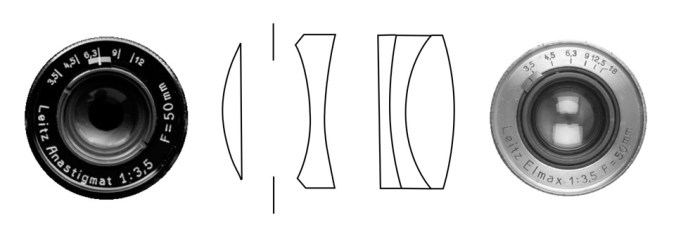

Why was the 50mm lens considered the “normal” lens used on 35mm cameras? Why not 40mm or 60mm? When Barnack introduced his revolutionary Leica camera, he used a traditional method of selecting the lens – the most commonly used lens has a focal length should be approximately equal to the diagonal of the negative, which is how the 50mm likely evolved. The Leica I came with a fixed 50mm lens, and even when the Leica II appeared in 1932 with interchangeable lenses, the viewfinder was designed to work with 50mm lenses. Zeiss Contax lens brochures from the 1930s mark 50mm lenses as “universal lenses”, “For all-round use and subjects which occur in every-day photography…”. Nikon also made the point that “Nikkor normal lenses cover a picture angle of approximately 45°, corresponding closely to the angle of view of the human eye”.

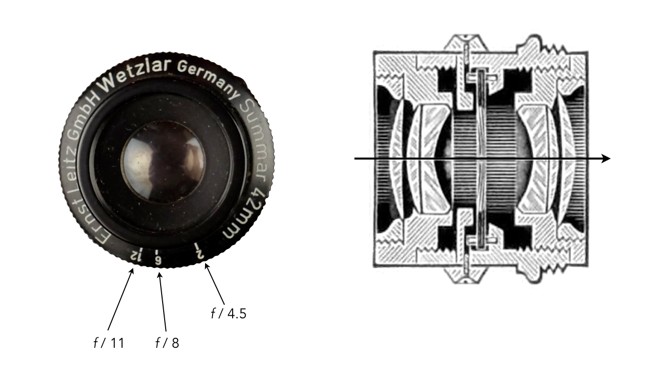

It is then no surprise that 50mm is the most ubiquitous analog lens. By the 1950s, most interchangeable lens cameras came standard with a 50mm lens, ensuring that novice photographers could capture sharp photographs in a variety of conditions without requiring a books worth of knowledge. Nikon in one of their lens brochures suggested “the 50mm focal length has become the standard lens for all around work”. This deep-seeded ideology is probably why 50mm lenses came in so many speeds – the same Nikon brochure provides an f/3.5, f/2, f/1.4, and f/1.1 50mm lenses. Many camera manufacturers followed suit. The late 1970s “standard” line-up for Asahi Pentax included four 50mm lenses (f/1.2, f/1.4, f/1.7, f/2) and a 40mm f/2.8 which they touted as being “extremely versatile”.

There are a number of arguments that have traditionally been made as to why 50mm is “normal”. The most common argument of course is that the 50mm lens has a diagonal angle-of-view (AOV) of about 45° which approximates the AOV of the human eye. But in reality it makes assumptions about what “normal vision” is , and the ability of a 50mm lens to reproduce it. The idea that 50mm best approximates human vision has more to do with the evolution of lenses than it has to do with any correspondence between the human eye and a lens. There are other arguments, for instance that 50mm reproduces facial proportions, depth and perspective roughly as how our eyes perceive them. Many manufacturers drove this point home by saying 50mm lenses “give pictures of natural, i.e. normal, perspective”.

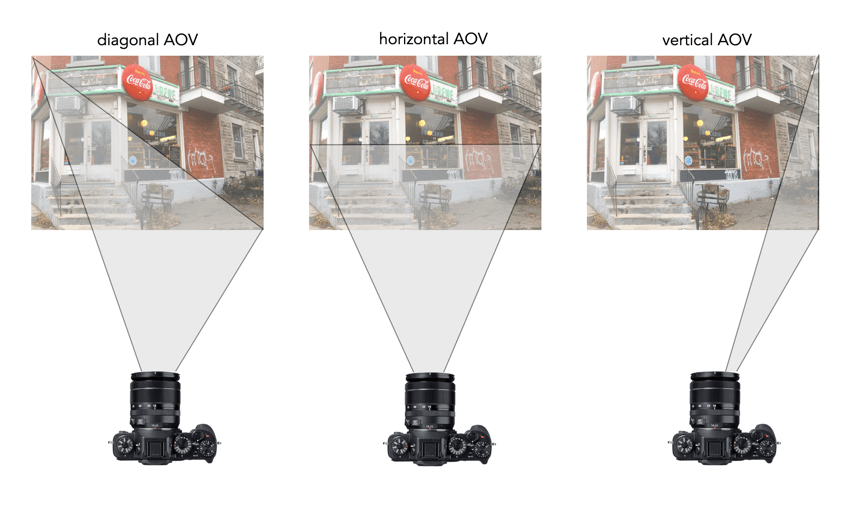

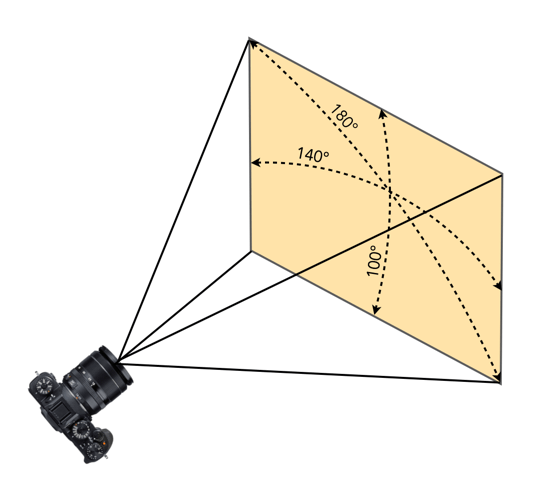

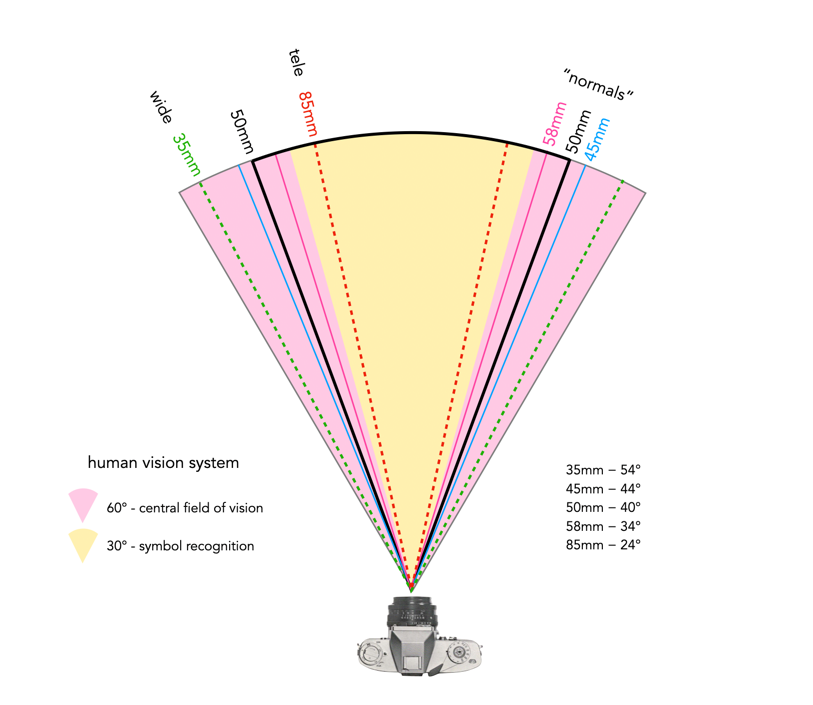

Firstly we should remember that “normal” human vision is binocular, while camera lenses are not. The eye is also composed of a gel-like material, versus the glass of lens elements. So there are already fundamental structural and functional differences. There is also the matter of AOV. A lens generally has one AOV, whereas the human visual system (HVS) has a series, based on differing abilities to focus – binocular vision is approximately 120° of view, of which only 60° is the central field of vision (the remainder is peripheral vision), and only 30° of that is vision capable of symbol recognition (even less is capable of sharp focusing, perhaps 5°?). Note that I use horizontal AOV in comparisons, because it is easier for people to conceptualize than diagonal AOV.

In reference to Figure 3, for the hard limits, a 67mm lens would likely best approximate the 30° region of the HVS that deals with symbol recognition, whereas a 31mm would best approximate the 60° central field of vision. If we were simply to take the middle ground, at 45°, we get a 43mm lens, which actually matches the diagonal of the 24×36mm frame.

But how closely does the 50mm AOV resembles that of the human visual system (HVS)? In terms of horizontal vision, a 50mm lens has a 40° AOV, so it’s not that far removed from that of the 43mm lens. Part of the problem lies with the fact that it is hard to establish an exact value that represents the “normal viewing angle” of the HVS. This is why other lens fit into this “normal” category – the 40mm (48°), the 45mm (44°), the 55mm (36°) and the 58mm (34°). Herbert Keppler may have put it best in his book The Asahi Pentax Way (1966):

“A normal focal length lens on any camera is considered to be a lens whose focal length closely approximates the diagonal of the picture area produced on the film. With 35mm cameras, this actually works out to be about 43mm, generally considered a little too short to produce the best angle of coverage and most pleasing perspective. Consequently, makers of 35mm cameras have varied their “normal” focal lengths between 50 and 58mm. With early single lens reflexes the longer 58mm length was in general use. However, in recent years there seems to be a trend to slightly shorter focal lengths which produce a greater angle of view. Current Pentax models use both 50 and 55mm focal length lenses.”

In some respects it seems like 50mm was chosen because it is close to what could be perceived as the AOV of the HVS, such that it is, and provided a nice rounded focal length value. By the 1950s, the 50mm had become “the standard” lens, with 35mm and 85mm lenses providing wide and telephoto capabilities respectively (a 35mm lens has an AOV of 54°, and the 85mm lens has an AOV of 24°, and surprisingly, 50mm sits smack dab in the middle of these). Many brochures simply identified it as an “all-round” lens. It is difficult to pinpoint where the reference of 50mm approximating the AOV of the human eye may have first appeared.

With the move to digital, the exact notion of a 50mm “normal” lens has not exactly persevered. This is primarily because the industry has moved away from 36×24mm being the normal film/sensor size, even though we hang onto the idea of 35mm equivalency. While a 50mm lens might be considered “normal” on a full-frame sensor, on an APS-C sensor a “normal” lens would be 35mm, because it is “equivalent” to a 50mm full-frame lens, from the perspective of focal length and more importantly AOV. Note that Zeiss still allude to the fact that the “focal length of the ZEISS Planar T* 1.4/50 is equal to the perspective of the human eye.”