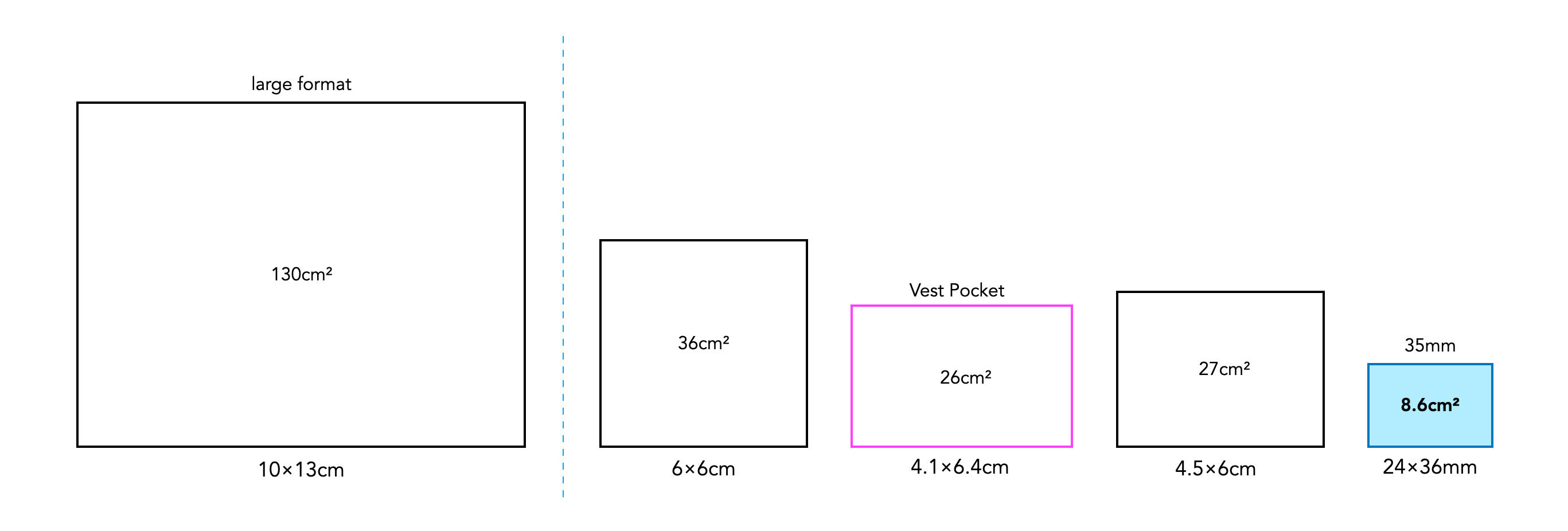

In the years following the arrival of the Leica (1926) the process of using it came to be known as ‘miniature photography’. Magazines of the period were full of techniques under the heading ‘miniature camera’, and the term itself would last until the early 1950s (the term was unknown before the Leica). Prior to this it was the age of large format cameras, which is any format larger than 9×12cm with one of the most common being the 10×13cm (4×5″). Probably the smallest format camera prior to 1926 was the Kodak Vest Pocket (VP) camera (1912-1934) which produced an image 2½×1⅝” (6.4×4.1cm) in size. By the early 1930s, photographers had become very miniature camera conscious. Big was out, small was in, but miniature started to evolve beyond 35mm, including any camera which took pictures smaller than 6×6cm (2¼×2¼”).

The question is why were formats like 6×6cm included in the definition of miniature? Inevitably, in view of the success of 35mm film cameras like the Leica other cameras began to appear in the category, essentially creating an industry within an industry in which manufacturers vied with one another to produce innovations based on the miniature theme. However in many cases these manufacturers just broadened the category to fit their camera rather than produce anything innovative. By the mid-1930s, there were circa four categories of miniature cameras:

- Small roll-film, film-pack or plate cameras, with negatives 2¼×3¼” or smaller that have one lens and a fixed bellows. Cameras included the Zeiss Ikonta (4.5/6/9×6cm), Foth Derby(24×36), Kodak Retina (24×36mm), and Voigtländer Virtus (4.5×6cm).

- Rangefinder cameras with a single lens or interchangeable lenses with negative sizes from 24×36mm to 2¼×3¼”. Cameras included the Leitz Leica and Zeiss Contax (24×36mm), Zeiss Super Ikonta (4.5/6×6cm) and Super Nettel (24×36mm).

- Single lens reflex cameras, which have a single lens with negatives ranging from 24×36mm to 4×6.5cm. This includes cameras like the Exakta (4×6.5cm), Kine Exakta (24×36mm), National Graflex (6×6.5cm), and Noviflex (6×6cm).

- Twin lens reflex cameras which have two lenses, and Cameras included the likes of the Rolleiflex and Rolleicord (6×6cm), Zeiss Ikoflex (6×6cm), Voigtländer Brilliant and Superb (6×6cm), Welta Perfekta (6×6cm). Many of these were limited to a single focal length. Another camera was the Zeiss Contaflex (24×36mm) which had a built-in electric cell exposure meter.

Indeed the March 10th, 1937 issue of The Amateur Photographer & Cinematographer outlines the ‘Modern Miniature Cameras’ available at the time by size [3]: a total of 98 cameras − 24×36mm (20), 24×36mm reflex (2), 3×4cm (15), 3×4cm reflex (1), 4×4cm reflex (1), 4×6.5cm (8), 4×6.5cm reflex (3), 4×6.5cm on 3¼×2¼ film (23), 6×6cm on 3¼×2¼ film (7), 6×6cm reflex (13), and five non-standard.

In late 1936 a heated debate on the topic started in the ‘Letters to the Editor’ section of The Amateur Photographer & Cinematographer. It stemmed from an article in the November 4th 1936 issue titled ‘What is a Miniature Camera?’ [1]. In it the definition of a miniature camera was one which took a picture of 6×6cm (2¼×2¼) or less. However the article also suggested that a camera taking a 4.5×6cm picture on 3½×2½ film (using a mask) could also be classed as a miniature. What followed was a litany of responses. In the Jan.6 1937 issue, one B.Z. Simpson suggested that “the only rationale definition of the miniature camera relates to the area of the negative used which must for the purpose be smaller than the V.P. size negative.” He goes on to say that “cameras using V.P. size… are not miniature at all, but ordinary size cameras.” [2].

Now we have 2¼” square and even 3¼×2¼” users crying out to be allowed within the ‘select circle’. If this matter goes much farther we shall shortly have the man with the half-plate calling himself a miniaturist.

Murdoch, J.N., “Letters to the Editor: Miniature Cameras”, The Amateur Photographer & Cinematographer, Jan.13 (1937)

Some seemed to settle on the idea of 5 square inches being the threshold, which would include 2¼×2¼ (6×6cm) cameras. Other objected to 6×6cm cameras being left out on the principle that the square shape utilizes the maximum area of the circular lens field (never mind that to compare a square image to a 24×36mm you would really be talking about a 36×36mm). Still others seemed to think the concept of miniature could be defined based on the focal length of the normal lens employed, e.g. 5cm for 24×36mm. It seemed that no-one wanted to be left out. The trend would continue until the industry was interrupted by the war, after which it was fundamentally altered.

By the early 1950s, the 6×6 had morphed on into its own category, the medium-format camera, and many of the other formats had disappeared altogether as the world’s photographers embraced 35mm. The miniature category itself contracted back to 35mm, but opened to include many differing types of 35mm. Here are some 35mm camera types from the early 1950s:

- Rangefinder cameras with interchangeable lenses − e.g. Canon IV-S2, Zeiss Contax IIa/IIIa, Foca Universal, Leica IIf/IIIf, Nikon

- Rangefinder cameras with fixed lenses − e.g. Argus C4, Kodak Retina IIa, Voigtländer Vitessa

- Rangefinder cameras with fixed lenses + separate film-shutter wind − e.g. Zeiss Ikon Contessa 35, Konica I/II, Voigtländer Vito III.

- Viewfinder cameras with fixed lenses + separate film-shutter wind − e.g. Argus A4, Zeiss Ikon Contina, Welta Welti, Kodak Retinette, King Regula I/II, Braun Paxette

- Rapid sequence cameras − e.g. Robot Star

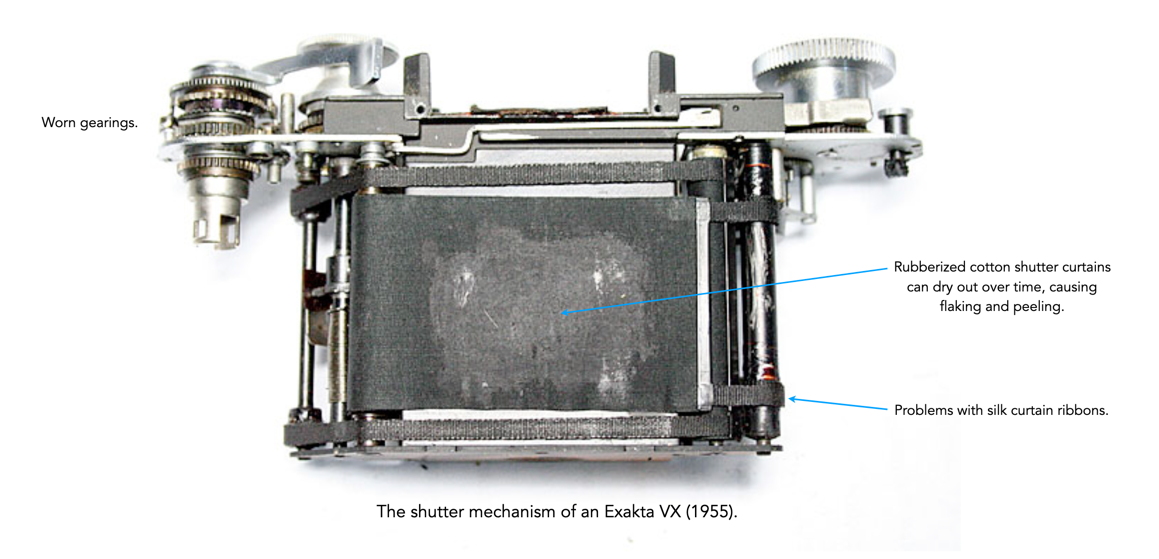

- Reflex cameras, waist-level − e.g. Alpa 4, Exa, Exakta VX, Praktiflex FX, Praktica FX

- Reflex cameras, eye-level − e.g. Alpa 5/6, Contax S/D, Rectaflex

Further reading:

- “What is a Miniature Camera?”, The Amateur Photographer & Cinematographer, p.15 Nov.4 (1936)

- Simpson, B.Z., “Letters to the Editor: What is a Miniature Camera?”, The Amateur Photographer & Cinematographer, Jan.6 (1937)

- “Modern Miniature Cameras”, The Amateur Photographer & Cinematographer, pp.40-46, Mar.10 (1937)