“He practices his own special brand of outside-looking-in photography. He roams he world with a Leica. About 90 percent of his pictures are made with 50-mm normal-focus lenses. He never poses. He never arranges. If observed, he instantly breaks off action. He adds no photographic lighting, but uses light exactly as he finds it. He eschews every specialized optical effect, from limited depth of field to ultra-wide-angle vision. In effect, he is the theoretically ideal photographer who sees without being seen, records without impinging upon his subjects.”

Bob Schwalberg, “Cartier-Bresson Today”, Popular Photography, 60(5), P.108 (1967)

Author: spqr

Vintage cameras – The mirror returns!

One of the biggest problems with early SLR camera’s was the fact that the mirror did not return to it’s position after the shutter was released, leaving a black void in the viewfinder. To facilitate this one had to wind on the next frame. Consider the pre-WW2 Exakta Kine, a purely waist-level camera. When the shutter release was pressed, spring action caused the mirror to fly upwards just before the shutter travelled. The Contax S used the same system. There were two issues with this: (i) the potential for the mirror action to cause jarring, making sharp images problematic, and (ii) once the shutter-release was pressed, the finder goes black, the the image disappeared (preventing the photographer from seeing the scene at the instant of the exposure, or after it). All this changed with the appearance of the instant return mirror. Many attribute this to the Asahi Asahiflex IIb camera in 1954.

However in reality the instant return mirror was the brainchild of Hungarian inventor and photographer Jenő Dulovits (1903-1972). He patented the worlds first eye-level SLR viewfinder in Hungary on August 23, 1943 [1]. The lead to the first camera sporting this new feature, the Duflex (DUlovits reFLEX). Because at the time the use of a pentaprism was deemed too expensive, the camera used a Porro prism – an arrangement of mirrors that would bring the light beams in through the lens, then reflected via mirrors upwards to meet the eye. Working prototypes were built at Gamma in Budapest in 1944, with the first camera put on the market in 1949 (hence why the camera is known as the Gamma Duflex).

Production lasted roughly a year with circa 550 units being produced (according to historian Zoltan Fejer – Hungarian Cameras, Budapest 2001). In all likelihood production ceased due to pressure from the Soviets – manufacture of Exaktas, Practicas etc. in East Germany, and Russian Zeniths likely meant that competition from a Hungarian camera maker was not wanted. However this decision likely set back their own camera designs by a decade. However Dulovits invention likely paved the way for future enhancement that would lead to Asahi’s commercially successful cameras, starting with the Asahi Asahiflex IIb. As Bob Schwalberg put it:

“A single-lens reflex innovation deserving special applause is the Asahi Optical Co.’s instant-return mirror, which flips up and out of the way just before exposure, and immediately snaps back to focusing position after the shutter has closed. … By eliminating the characteristic reflex blackout, the doubly-sprung Asahi mirror permits the photographer to continue focusing and/or framing without the interruption of having first to transport the film as in traditional reflex-cameras.”

Bob Schwalberg, “35-mm Today: Onward and Upward! Part II”, 42(2) pp.12 (Feb.1958)

✽ Dulovits camera patents appear on the website of the Hungarian Intellectual Property Office. Outside of Hungary, the only patents available are for his soft effect lenses. The camera actually heralded other firsts, including internal automatic diaphragm control, and a metal focal plane curtain shutter.

Note: The first quick return reflex mirror is sometimes attributed to the KW Praktiflex, which debuted in 1939. However in the Praktiflex the mirror is raised as the shutter release is pressed, and falls back under gravity when the button is released, i.e. not really an instant return mirror, more of a shutter-release-actuated mirror.

Further reading:

- Jenő Dulovits, No.167464 (D-5859), “Eye-level SLR camera”, (Aug.23, 1943)

Why are superfast aperture lenses so big?

A 50mm lens is always a 50mm right? They are in terms of focal length, but shouldn’t they all have similar dimensions? So why are lenses with super/ultra-wide apertures sometimes so much larger, and hence so much more expensive?

If there has been one notable change in the evolution of lenses, it has been the gradual move towards larger (faster) apertures. The craze for superfast lenses began in Japan in the 1950s, with Fujinon introducing the first f/1.2 5cm lens in 1954. After the initial fervour, it seems like the need for these lenses with large apertures disappeared, only reappearing in the past decade while at the same time moving into the realm of sub-f/1 ultrafasts. There are many advantages to ultra wide aperture lenses, but basically fast lenses let in a lot of light, and more light is good. The simple reason why bigger aperture equals bigger lens is more often than not to do with the need for more glass. It was no different with historical superfast lenses. The Canon 50mm f/0.95 which debuted in 1961 was 605g.

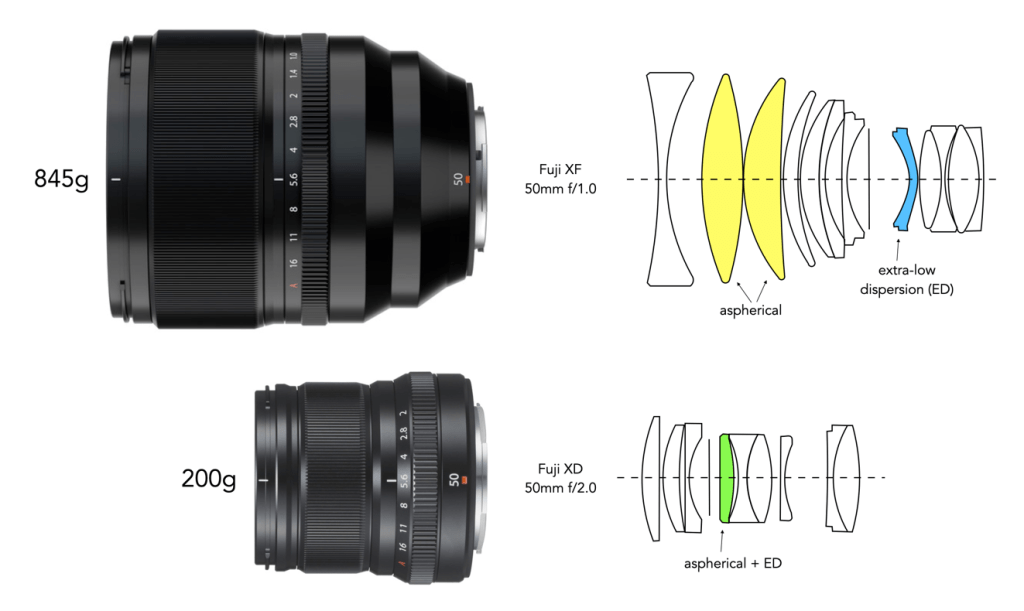

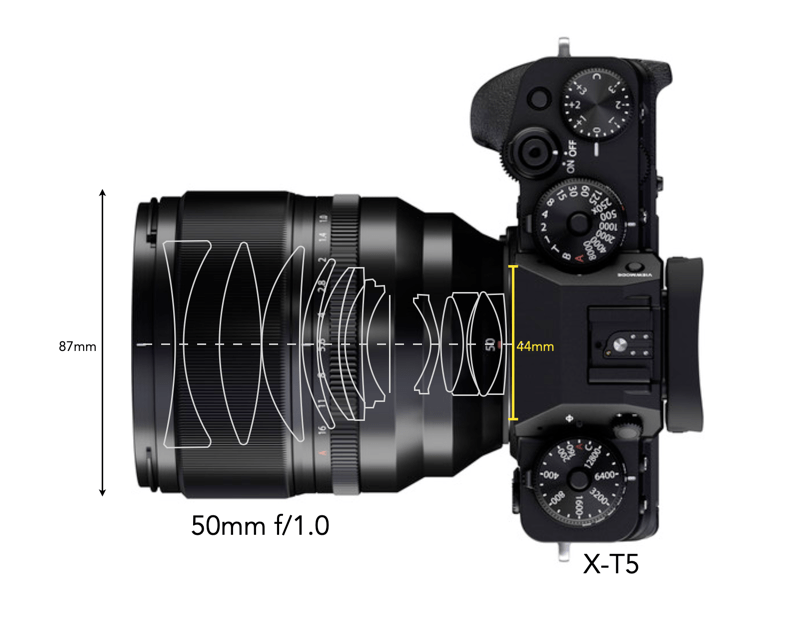

Lenses are designed with the maximum aperture in mind. For example, a 50mm f/2.8 lens only needs an aperture with a maximum opening of 17.8mm (50/2.8), however a 50mm f/1.4 will need a maximum aperture opening of 35.7mm (note that these apertures are based on the diameter of the entrance pupil). For example consider the following two Fujifilm 50mm lenses – the “average” f/2.0 and the 2-stop faster f/1.0:

- Fujifilm XF 50mm f/1.0 R WR – 845g, L103.5mm, ⌀87mm, 12/9 elements

- Fujifilm XD 50mm f/2.0 R WR – 200g, L59mm, ⌀60mm, 9/6 elements

The f/1.0 is over four times as heavy as the f/2.0, and almost double the length. To get an f/2.0 on a 50mm lens you only need a 25mm aperture opening, however with a f/1.0 lens, you theoretically need a 50mm opening (aperture of the entrance pupil). Now some basic math of the surface area (SA) of an aperture circle will provide a SA of 491mm2 for the f/2.0, but a whopping 1963mm2 for the f/1.0, so roughly four times as much area which allows light to pass through fully open. Equating this to glass probably means that at least four times as much glass is needed for some of the elements in the f/1.0 lens. There is no way around this – large apertures need large glass. As the aperture of a lens increases, all of the lenses have to be scaled up to achieve the desired optical outcome.

Larger aperture lenses also have more specialized glass in them, like with aspheric and low dispersion elements. But companies don’t just add more glass to make money – complex designs are supposed to overcome many of the limitations that are present in ultra-wide aperture lenses. Unlike their historical predecessors, modern superfast lenses have overcome many of the earlier lens deficiencies. For example in vintage superfast lenses, the lens wide-open was never as sharp as could be expected. Newer lens on the other hand are just as sharp wide open as they are stopped down to a smaller aperture.

Now not all super/ultra-wide aperture lenses are heavy and large. There are a number of 3rd-party lenses that are quite the opposite – reasonable size, and not too heavy (and invariably cheaper). But there is no such thing as a free lunch – there is always some sort of trade-off between price, size and optical quality. For example the Meike 50mm f/0.95 is only 420g, and it’s lens configuration is 7 elements in 5 groups. However fully open it is said to exhibit a good amount of chromatic aberration, some barrel distortion, and some vignetting. There is no perfect lens (but the Fuji f/1.0 comes pretty close).

✿ A fast lens is one with a wide maximum aperture. Superfast lenses are typically f/1.0-1.2, and ultrafast lenses are sub-f/1.0.

Further reading:

- Fujifilm 50mm f/1 Lens Review, Shotkit

How SLRs changed the camera landscape

“The triggering mechanism that released a flood of new lens designs was the emergence of the 35-mm SLR as a practical, rapid, and flexible camera during the mid-1950s. Then the Contax S from East Germany introduced eyelevel camera operation by incorporating a pentaprism for the first time, and the Asahiflex II from Japan ushered in the instant-return reflex mirror. Once these two features were combined with the gradually evolved auto-diaphragm, the 35-mm SLR became the vehicle for most of the new and interesting lens design.”

Norman Goldberg, “The Miracle of Modern Lenses”, The Best of Popular Photography (1979)

Superfast lenses – the Fujinon 5cm f/1.2

In the 1950s, the Japanese camera industry was at war, and the prize was super-fast lenses. There were several manufacturers involved in this race – Zunow, Nippon Kogaku, Konishiroku and Fujinon. Although the ultimate target was likely the German optical industry. The Fujinon 5cm f/1.2 was to appear in 1954. It was built in the Leica LTM screw mount (800 pieces), the Nikon S rangefinder mount (50 pieces) and the Contax S mount.

The lens was designed by Fuji designer Ryoichi Doi. The lens is said to have been based on the Solinon 5cm f/1.5, which was also designed by Doi and patented in 1948 (J#191,452). The lens was based on Sonnar design, and the next step was to push it to f/1.3 using conventional glass. This was followed by a prototype f/1.2 with 9 elements, and finally the production 8-element design. Six of the eight lens optics were high speed lenses. These lenses used four types of new types of glass with low refractive index and high dispersion, the aim being to minimize flare caused by aberrations and achieve high-contrast imaging. The lens was designed to ensure ample light reached the edges of the frame, having a front lens diameter was 51.5mm, and the rear lens diameter was 28mm.

A 1959 price list shows that this lens sold for US$299.50. Today the price of this lens is anywhere north of $20K. Too few were manufactured to make this lens the least bit affordable.

The term “crop-sensor” has become a bit nonsensical

The term “crop-sensor” doesn’t make much sense anymore, if it ever did. I understand why it evolved, because a term was needed to collectively describe smaller-than-35mm sized sensors (crop means to clip or prune, i.e. make smaller). That is, if it’s not 36×24mm in size it’s a crop-sensor. However it’s also sometimes used to describe medium-format sensors, even though they are larger than 36×24mm. In reality non-35mm sensors do provide an image which is “cropped” in terms of comparison with a full-frame sensor, but taken in isolation they are sensors unto themselves.

The problem lies with the notion that 36×24mm constitutes a “full-frame”, which only exists as such because manufacturers decided to continue using the concept from 35mm film SLR’s. It is true that 35mm was the core film standard for decades, but that was constrained largely by the power of 35mm film. Even half-frame cameras (18×24mm, basically APS-C size) used the same 35mm film. In the digital realm there are no constraints on a physical medium, yet we are still wholly focused on 36×24mm.

Remember, there were sub-full-frame sensors before the first true 36×24mm sensor appeared. Full-frame evolved in part because it made it easier to transition film-based lenses to digital. In all likelihood in the early days there were advantages to full-frame over its smaller brethren, however two decades later we live in a different world. “Crop” sensors should no longer be treated as sub-par players in the camera world. Yet it is this full-frame mantra that sees people ignore the benefits of smaller sensors. Yes, there are benefits to full-frame sensors, but there are also inherent drawbacks. It is the same with the concept of equivalency. We say a 33mm APS-C lens is “equivalent” to a 50mm full-frame. But why? Because some people started the trend of relating everything back to what is essentially a 35mm film format. But does there even need to be a connection between different sensors?

The reason “crop” sensors have continued to evolve is because they are much cheaper to produce, and being smaller, the cameras themselves have a reduced footprint. Lenses also require less glass, making them lighter, and less expensive to manufacture. Maybe instead of using “crop-sensor”, we should just acknowledge the sensors exactly as they are: Medium, APS-C, and MFT, and change full-frame to be “35mm” format instead. So when someone talks about a 35mm sensor, they are effectively talking about a full-frame. All it takes is a little education.

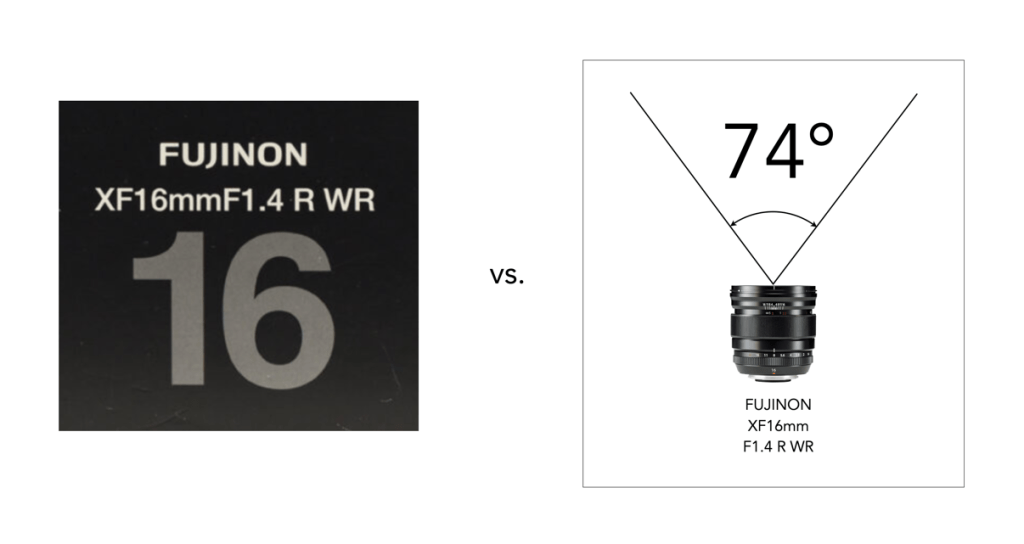

Using the term-crop sensor also does more harm than good, because it results in more terms: equivalency and crop-factor which are used in the context of focal length, AOV, and even ISO. People get easily confused and then think that a lens with a focal length of 50mm on an APS-C camera is not the same as one on a FF camera. Focal lengths don’t change, a lens that is 50mm is always 50mm. What changes is the Angle-of-View (AOV). A larger sensor gives a wider AOV, whereas a smaller sensor gives a narrower AOV. So while the 50mm lens on the FF camera has a horizontal AOV of 39.6°, the one on the APS-C camera sees only 27°.

It would be easier not to have to talk about a sensor in terms of another sensor. But even though terms like “crop-sensor” and “crop-factor” are nonsensical, in all likelihood the industry won’t change the way they perceive non-35mm sensors anytime soon. I have previously described how we could alleviate the term crop-factor as it relates to lenses, identifying lenses based on their AOV rather than purely by their focal length. This works because nearly all lenses are designed for a particular sensor, i.e. you’re not going to buy a MFT lens for an APS-C camera.

From photosites to pixels (iv) – the demosaicing process

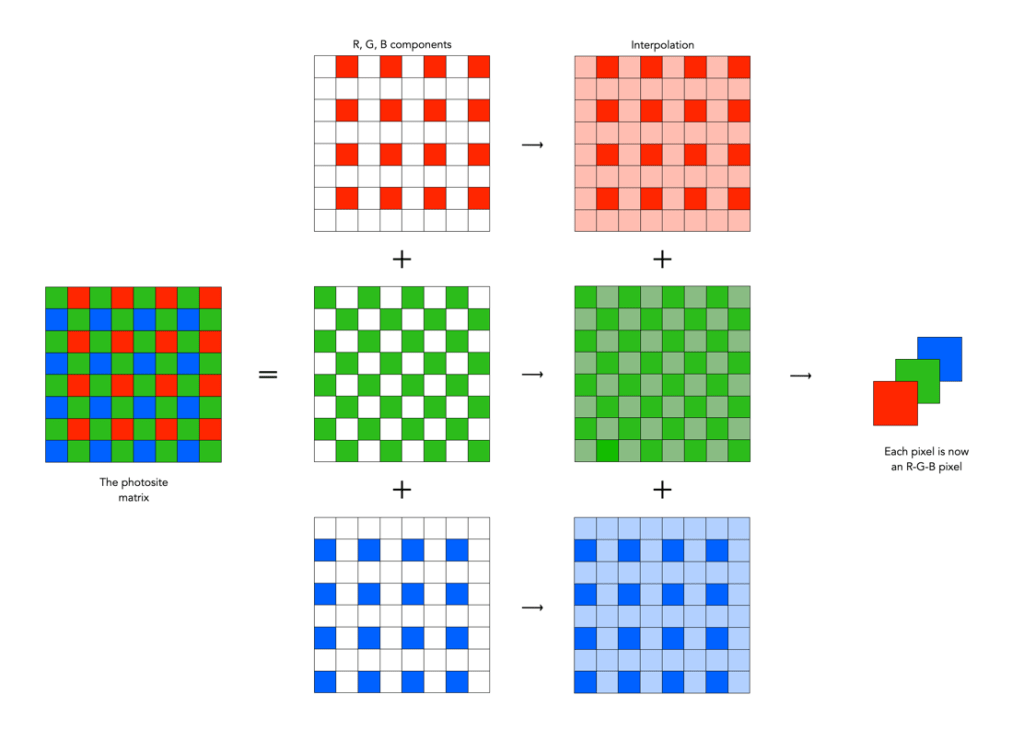

The funny thing about the photosites on a sensor is that they are mostly designed to pick up one colour, due to the specific colour filter associated with with photosite. Therefore a normal sensor does not have photosites which contain full RGB information.

To create an image from a photosite matrix it is first necessary to perform a task called demosaicing (or demosaiking, or debayering). Demosaicing separates the red, green, and blue elements of the Bayer image into three distinct R, G, and B components. Note a colouring filtering mechanism other than Bayer may be used. The problem is that each of these layers is sparse – the green layer contains 50% green pixels, and the remainder are empty. The red and blue layers only contain 25% of red and blue pixels respectively. Values for the empty pixels are then determined using some form of interpolation algorithm. The result is an RGB image containing three layers representing red, green and blue components for each pixel in the image.

There are a myriad of differing interpolation algorithms, some which may be specific to certain manufacturers (and potentially proprietary). Some are quite simple, such as bilinear interpolation, while others like bicubic interpolation, spline interpolation, and Lanczos resampling are more complex. These methods produce reasonable results in homogeneous regions of an image, but can be susceptible to artifacts near edges. This leads to more sophisticated algorithms such as Adaptive Homogeneity-Directed, and Aliasing Minimization and Zipper Elimination (AMaZE).

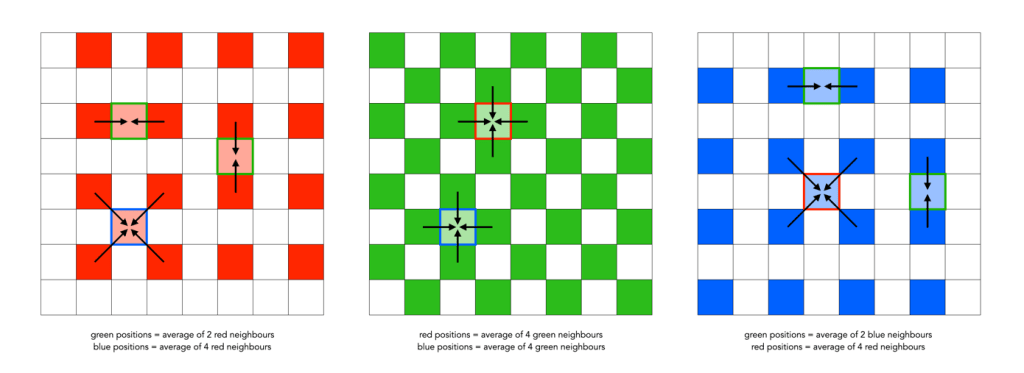

An example of bilinear interpolation is shown in the figure below (note that no cameras actually use bilinear interpolation for demosaicing, but it offers a simple example to show what happens). For example extracting the red component from the photosite matrix leaves a lot of pixels with no red information. These empty reds are interpolated from existing red information in the following manner: where there was previously a green pixel, red is interpolated as the average of the two neighbouring red pixels; and where there was previously a blue pixel, red is interpolated as the average of the four (diagonal) neighbouring red pixels. This way the “empty” pixels in the red layer are interpolated. In the green layer every empty pixel is simply the average of the neighbouring four green pixels. The blue layer is similar to the red layer.

❂ The only camera sensors that don’t use this principle are the Foveon-type sensors which have three separate layers of photodetectors (R,G,B). So stacked the sensor creates a full-colour pixel when processed, without the need for demosaicing. Sigma has been working on a full-frame Foveon sensor for years, but there are a number of issues still to be dealt with including colour accuracy.

Galileo’s homemade telescope

“This I did shortly afterwards, my basis being the theory of refraction. First I prepared a tube of lead , at the ends of which I fitted two glass lenses, both plane on one side while on the other side one was spherically convex. Then placing my eye near the concave lens I perceived objects satisfactorily large and near, for they appeared three times closer and nine times larger than when seen with the naked eye alone .”

− Galileo Galilei published the initial results of his telescopic observations of the heavens in Starry Messenger (Sidereus Nuncius) in 1610

Vintage camera makers – The origins of Pentacon

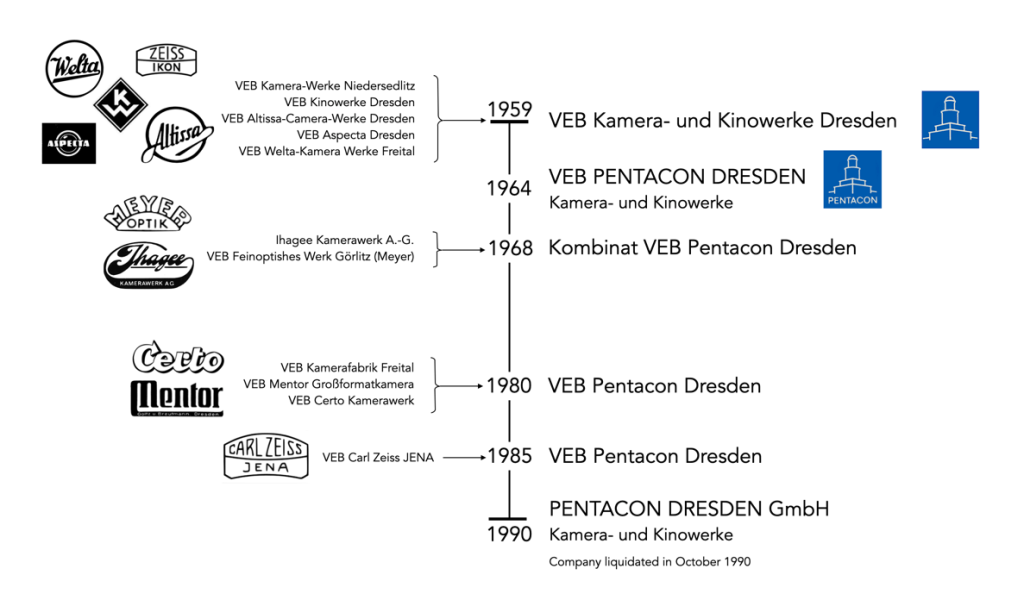

Post-WW2 there were still a lot of camera companies in Germany, and particularly in East Germany. In fact the heart of the German camera industry lay in Dresden, Jena and the surround area. Over the next decade, many of the companies were merged into a series of VEBs (Volkseigener Betrieb or Publicly Owned Enterprise) culminating with VEB Pentacon.

On January 1, 1959 a series of Dresden camera manufacturers were merged to create the large state-owned VEB Kamera und Kinowerke Dresden (KKWD). The company was a conglomerate of existing companies which produced a broad range of products and had numerous production sites. Joining them together meant production could be rationalized, yet cameras were still produced under their brands names, e.g. Contax, Welta, Altissa, Reflekta, Belfoca.

- VEB Kinowerke Dresden − Formerly VEB Zeiss Ikon

- VEB Kamera-Werke Niedersedlitz − This is where the Praktiflex, precursor of the Praktica, was invented; it included VEB Belca-Werk absorbed in 1957.

- VEB Welta-Kamera Werke Freital − This included the VEB Reflekta-Kamerawerk Tharandt and Welta-Kamera-Werk Freital (Reflekta II, Weltaflex und Penti).

- VEB Altissa Kamerawerke Dresden − Formerly Altissa-Camera-Werk Berthold Altmann, (including Altissa, Altiflex and Altix cameras).

- VEB Aspecta Dresden − Formerly Filmosto-Projektoren Johannes (including projectors, enlargers, lenses).

In 1964 the company was renamed to VEB Pentacon Dresden Kamera-und Kinowerke. This was intended to provide a catchy name for the company (not forgetting that a lot of its products were intended for Western markets). Pentacon was already being used as the export name for the mirror Contax D, and was derived from PENTAprisma and CONtax. Pentacon used the stylized silhouette of the Ernemann Tower (on the old Ernemann camera factory site, which belonged to the former Zeiss Ikon) as its corporate logo. The company continued to produce good SLRs: Praktica V (1964), Praktica Nova with return mirror (1964), Praktica Nova B with uncoupled light meter (1965), Praktica Mat for the first time with TTL interior light metering (1965). In 1966 the 6×6 format Pentacon Six appeared, with the Praktica PL Nova I in 1967.

On January 2, 1968, the VEB was restructured, and more companies were added into the fold, including Ihagee Kamerawerk (which had remained independent until this point), and VEB Feinoptisches Werk Görlitz. The name became Kombinat VEB Pentacon Dresden.

- Ihagee Kamerawerk AG i.V. − Produced Exakta and Exa cameras.

- VEB Feinoptisches Werk Görlitz − Formerly Meyer-Optik Görlitz

The continuous expansion and bundling of technical expertise and concentration of the production capacities of the Pentacon, led to the incorporation of three more companies in 1980.

- VEB Kameratechnik Freital − Formerly Freitaler camera industry Beier & Co., including Beirette cameras.

- VEB Mentor Großformatkamera − large format cameras

- VEB Certo Kamerawerk Dresden − folding cameras

On January 1, 1985, the VEB Pentacon, which by now had absorbed most of the East German camera industry was formally incorporated into Kombinat VEB Carl Zeiss Jena. This move amalgamated nearly the entire East German photography industry under the Zeiss umbrella. There were scarce few years between this and the reunification of Germany. After reunification, VEB Carl Zeiss Jena was reabsorbed into the Stiftung and was completely restructured. VEB Pentacon was renamed PENTACON DRESDEN GmbH, in July 1990, but by October it was being liquidated.

What is a mirrorless camera?

It is a camera without a mirror of course!

Next you’ll ask why a camera would ever need a mirror.

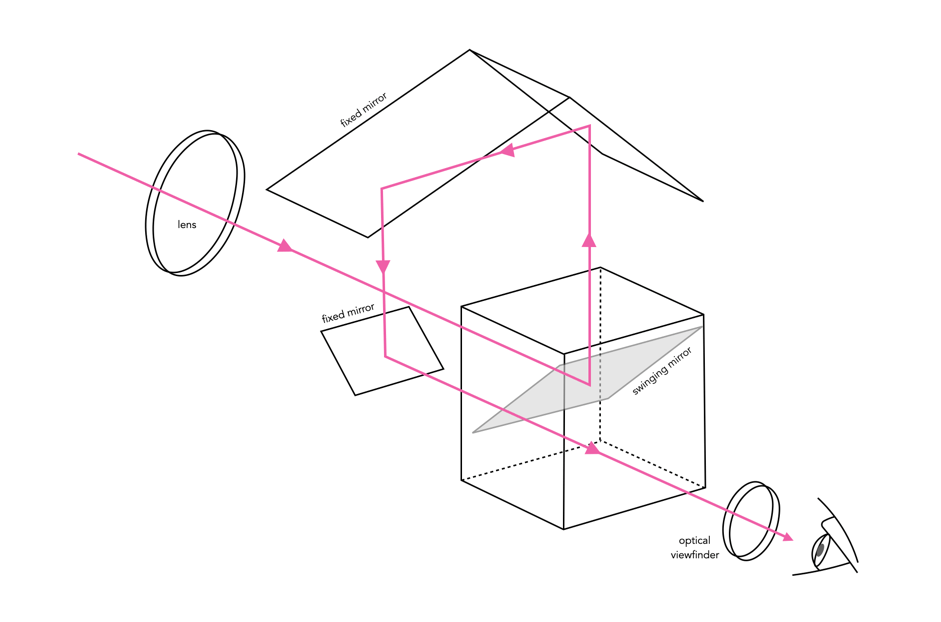

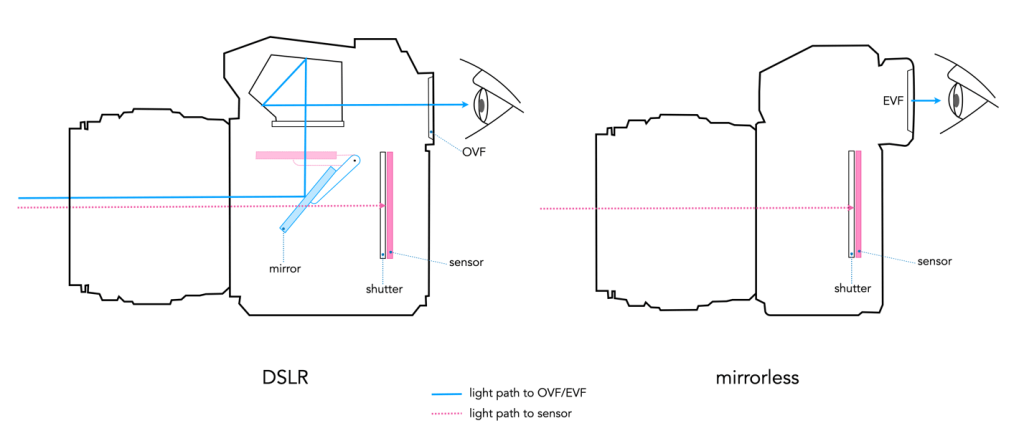

Over the last few years we have seen an increased use of the term “mirrorless” to describe cameras. But what does that mean? Well, 35mm SLR (Single Lens Reflex) film cameras all contained a reflex mirror. The mirror basically redirects the light (i.e. view) coming through the lens to the film by means of a pentaprism, to the optical viewfinder (OVF) – which is then viewed by the photographer. Without it, the photographer would have to view the scene by means of an offset window (like in a rangefinder camera, which were technically mirrorless). This basically means that the photographer sees what the lens sees. When the photographer presses the shutter-release button, the mirror swings out of the way, temporarily blocking the light from passing through the viewfinder, and instead allowing the light to pass through the opened shutter onto the film. This is depicted visually in Figure 1.

When DSLR (Digital Single Lens Reflex) cameras appeared they used similar technology. The problem is that this mirror, together with the digital electronics, meant that the cameras became larger than traditional film SLRs. The concept of mirrorless cameras appeared in 2008, with the introduction of the Micro-Four-Thirds system. The first mirrorless interchangeable lens camera was the Panasonic Lumix DMC-G1. It replaced the optical path of the OVF with an electronic viewfinder (EVF), making it possible to remove the mirror completely, hence reducing the size of cameras. The EVF shows the image that the sensor outputs, displaying the output on a small LCD or OLED screen.

As a result of nixing the mirror, mirrorless cameras are typically have fewer moving parts, and are slimmer than DSLRs, shortening the distance between the lens and the sensor. The loss of the mirror also means that it is easier to adapt vintage lenses for use on digital cameras. Some people still prefer using an OVF, because it is optical, and does not require as much battery-life as an EVF.

These days the only cameras still containing mirrors are usually full-frame DSLRs, and they are slowly disappearing, replaced by mirrorless cameras. Basically all recent crop-sensor cameras are mirrorless. DSLR sales continue to decline. Looking only at interchangeable lens cameras (ILC), according to CIPA, mirrorless cameras in 2022 made up 68.7% of all ILD units (4.07M versus 1.85M), and 85.8% of shipped value (out of 5.927 million units shipped).