Among the many things I resent about digital imaging is the slamming of the door on one of my favorite hobbies, camera collecting. Aside from getting a discontinued model cheap to use as a backup, can you tell me why someone would be excited about buying an obsolete digital camera for any purpose other than to use as a doorstop?

Herbert Keppler, On the joys of collecting. (Popular Photography & Imaging, August 2007)

Author: spqr

War reparations at Carl Zeiss Jena – where did the dismantled equipment go?

The Soviets reportedly stripped Carl Zeiss Jena of 93% of its equipment, most of which was redistributed throughout factories in the USSR. This included 14 of the 16 glass furnaces at Zeiss [4], machines, office supplies and equipment, stocks and raw materials, boilers, elevators, switchboards etc. [5]. So what happened to the equipment taken by the Soviets as war reparations from the Jena plant from October 1946 to April 1947?

The majority of the dismantled equipment was transferred to three cities in the USSR – Moscow, Leningrad, and Kiev [8]. To Moscow went the rangefinder equipment, to Leningrad the equipment for the production of microscopes, micrometers and fine measuring devices, and to Kiev the geodetic equipment and the Contax Camera section [8]. Most of it seems to have been transferred to two factories in Russia: No.349, and No.393.

The Optical-Mechanical Plant No.349 near Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) was founded in 1914 in Petrograd. In 1919 it was nationalized, and in 1921 it was renamed the Factory of State Optics. Further reorganizations resulted in the factory in Leningrad becoming Gosudarstvennyy Opticheskiy Mekhanicheskiy Zavod (GOMZ), or State Optical-Mechanical Factory, in 1932. In 1965 GOMZ changed its name to LOMO (Leningradskoe Optiko Mekhanichesko Obedinenie), or Leningrad Optical-Mechanical Union. They produced optics for the Soviet military and space programs, as well as consumer cameras. Seventy-nine of the Zeiss experts from Jena were assigned to GOMZ, and the existing equipment in various parts of the factory was replaced by equipment dismantled from Jena [2]. By mid-1947 the process was completed, and the Soviet personnel were trained on using the equipment. A CIA report on the facility [2] suggests that much of the dismantled equipment stored in the open, or spoiled by mishandling, and the Soviets gained very little from the seized equipment [2].

Zavod (factory) No.393 is located in the small town of Krasnogorsk, a few kilometers from Moscow. Krasnogorsky Zavod was founded in 1942. During the Soviet era it became known as Krasnogorskiy Mechanicheskiy Zavod (Krasnogorskiy Mechanical Works), or KMZ for short. After 1945 it began producing lenses to Carl Zeiss specifications. The machinery at No.393 seems to be almost entirely made up of machines dismantled from Zeiss, Jena [6]. All the grinding and polishing machines at No.393 were transferred from Jena, amounting to one-third of the entire Zeiss plant as it existed prior to dismantling (100 lens grinding machines, 300 milling machines, and 100 metal grinding machines) [3]. The largest segment of machines was the 400 lathes of various sizes. All optical glass used at No.393 from 1946 to 1952 was from Jena, and of good quality [3].

No.393 produced a lot of optical items, including the Zorky camera, designated “FED”, and associated 5cm lenses. The Zorky was essentially a copy of the Leica IIc manufactured during the period 1940-1944. By 1951, about 400 cameras per month were being produced [6]. By 1947 the plant also made Moscow II 6×9cm camera, aerial cameras, photo-rectifiers, phototheodolites, 16mm motion picture cameras, and a series of military items.

The Contax camera section went to Arsenal No.1 in Kiev, Ukraine [8]. By the later 1940s this plant was making reproductions of the Contax II and Contax III cameras. These would morph into Kiev II and III cameras, eventually modified into the Kiev and 4A and 4AM. Some of the equipment also made it to smaller factories in the USSR. A good example of this is Optical Plant No.230 near the small town of Lytkarino (not far from Moscow). They received 50-60 grinding and polishing machines from Jena [7], although the CIA reports this as “bad and uncared-for equipment”. Some of the equipment was used to outfit a vacant optical plant in Zagorsk. Zeiss specialists installed the machinery, and trained Soviet workers [1].

The dismantling was in many ways not considered to be optimally successful, in all likelihood because insufficient care was taken with the sensitive equipment [4].

✽ Please note that while some people seem to regard the Soviet dismantling of equipment in East Germany to be looting, it was actually part of the reparation payments agreed upon in the Potsdam Agreement.

Further reading:

Please note that the CIA links don’t seem to work sometimes (since the issues with the US government websites began).

- “Zeiss Specialists in the USSR”, Central Intelligence Agency, Information Report, 17 December (1952)

- “Optical-Mechanical Factory No.349 GOMZ in Leningrad”, Central Intelligence Agency, Information Report, 23 June (1954)

- “Quantity and Types of Optical Machinery and Equipment at Zavod 393 in Krasnogorsk and at Zeiss in Jena”, Central Intelligence Agency, Information Report, 25 August (1953)

- “Zeiss and Schott and Genossen, Jena”, Central Intelligence Agency, Information Report, 1 April (1947)

- “Organization and Production of the Carl Zeiss Plant at Jena”, Central Intelligence Agency, Information Report, 31 August (1953)

- “Production at Factory 393 at Krasnogorsk”, Central Intelligence Agency, Information Report, 20 August (1953)

- “Optical Plant in Lytkarino”, Central Intelligence Agency, Information Report, 19 January (1950)

- “Activities and Production at Arsenal No.1 Kiev”, Central Intelligence Agency, Information Report, 6 February (1953)

What about the other camera on Sister Boniface Mysteries?

Of course people are also going to ask about the second camera seen on Sister Boniface Mysteries… the one belonging to Ruth Penny, Editor-in-Chief of the Albion Bugle. What is clear is that it is an Asahi Pentax model, likely an S2, S3, or even an SV (again the “Asahi Pentax” label has been covered up, but the Asahi design is still present). The S2 was introduced in 1959, the S3 in 1961, or even the SV (1963). For the S2, the lens is likely the Auto-Takumar 55mm f/2, for the S3, the Auto-Takumar 55mm f/1.8. It’s hard to make an exact designation because the camera’s all have a similar form, and the specific type markings appear atop the camera near the film rewind lever.

The flash seems to be a Metz Mecablitz 101 from the late 1950s/early 1960s. Note that these cameras had different designations based on market: S designated cameras were for the Japanese and European markets, and H for the North American (NA) market (as Asahi Optical was represented in North America by Honeywell Corp). So the S2 was designated the H2 in the NA market.

What camera is used on Sister Boniface Mysteries?

In the first episode of Sister Boniface Mysteries (BritBox), we are introduced to Sister Boniface, a Catholic nun with a PhD in forensic science. Now part of her job as police scientific adviser involves taking photographs, obviously given the time period in the early 1960s, she uses a 35mm SLR camera – but what camera?

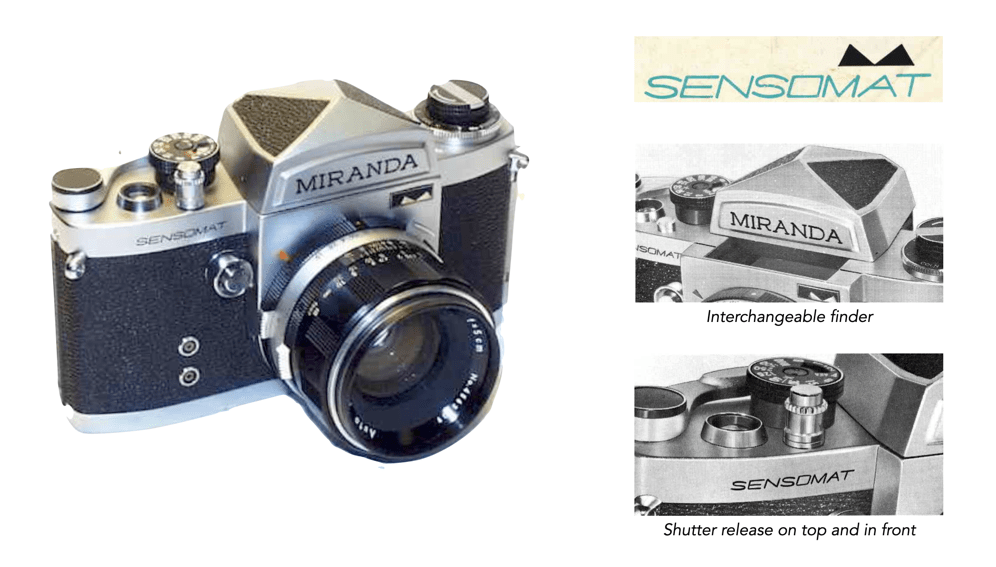

Well, it isn’t actually too hard to figure out the camera, despite the fact that the branding has been covered by black tape – the camera is from Japanese company Miranda, founded in 1947 and produced 35mm cameras from 1953 to 1976 (it was named Miranda Camera in 1957). During that period they introduced some 30 differing models nearly all with interchangeable pentaprism’s. The camera itself is a Miranda Sensomat, introduced in 1969. It was a budget camera, which had TTL CdS stop-down meter built-in the under mirror. The Sensomat range was produced from 1969-1974. The lens is likely the Auto-Miranda 50mm f/1.8, and the camera sold in 1969 for US$190 – it was advertised as being affordable.

The interesting thing about the use of this camera is that the series is set in the early 1960s, and the camera was released in 1969, so there is some historical disparity. If one were choosing a Miranda camera of the period, a Miranda D might have been more appropriate. As to why the Miranda was chosen? Likely it was just a prop, it’s doubtful anyone thought about using a more historically significant camera for the period. Why cover up the brand? Likely due to not having to pay licensing fees, although it is unclear as to who currently owns the Miranda trademark.

Further reading:

- Miranda Sensomat (1969) – Mike Eckman (2015)

- Miranda – PhilCameras

- Miranda Camera Family – SLR models

Beaton on failure

A technical “failure” which shows some attempt at aesthetic expression is of infinitely more value than an uninspired “success”.

Cecil Beaton in Photography (Odhams, 1951)

Vintage lenses: Beware of the “rare”

Some online photographic stores have lenses that are marked as “rare”. This is sometimes a bit of a red flag, because as is often the case, these lenses are not really rare. Rare sometimes indicates that the seller has priced the lens high, even if the lens has defects. It is possible that “rare” emanates from an internet search that found few comparable lenses. For example there is nothing rare about a Helios 44-2 58mm f/2 lens, certainly not one that usually sells for under $100. There may be some early versions of the lens, e.g. the early “silver” ones, that are less common, but the lens itself is not rare. Rare lenses do exist, but these are usually rare because few were produced, or few are available. The Helios-40, 85mm f/1.5 is a less-common lens, and could rightly be portrayed as rare. In many respects it would be better to use the term “uncommon” when describing lenses that have low availability, leaving “rare” for the truly rare lenses.

Truly rare lenses include the likes of the Fisheye Nikkor Auto 6mm f/2.8, which can be worth upwards of $150K. The Canon 50mm f/0.95 on the other hand could probably be considered uncommon, as only 20,000 were produced. The Konica Hexanon 60mm f/1.2 is even rarer, with only 800 units supposedly produced. However it is fairly hard to define a Zeiss Sonnar 135mm lens as being rare, because a lot were produced, and there is nothing inherently special about them just because they are branded ZEISS (they sell for about C$75) – vintage 135mm lenses are a dime a dozen. The only rare 135mm lenses are those from companies who produced very few, or the lenses themselves had some sort of interesting or exclusive characteristic.

There are many reasons a lens could be considered rare. Vintage lenses with small focal lengths, or super-fast speeds (for a particular period) will always be quite rare, because few were likely produced (they were expensive to produce). A good example is the Vivitar Professional 135mm f/1.5 (T-mount) – nobody would necessarily use the terms Vivitar and rare in the same sentence, but is a special lens. Possibly only a few hundred of the 135mm lenses were made, having been originally produced for NASA in 1966-1967. But it’s claim to fame is that it was a superfast 135mm (and it was super large, 140mm long, 100mm diameter, and 2kg in weight). There are few, if any, on the market today.

A further reason is that a lens may represent the first of a series, or has some particular historical significance. A good example is the first 35mm macro lens, the Kilfitt Macro Kilar D 40mm f/3.5. Or perhaps it is rare because it is a pre-war lens – for example associated with the release of the Kine Exakta, the first 35mm SLR. A good example of this is the famed Biotar 75mm f/1.5, released in 1939, and was the fastest portrait lens at the time. Still another form of rarity – one where a lens is very rare in one version, but commonplace in another, even though both versions being optically identical – usually has something to do aesthetic differences between the the lenses, or the amount of time it was in production.

Some lenses are marked “rare” for the pure shock value – because if people think a lens is rare, they will be more likely to purchase it. So before buying a lens make sure to determine whether the lens is in fact rare, and whether it warrants the price being asked. In addition avoid purchasing a rare lens that is severely deficient, e.g. has stiff focusing or aperture mechanisms, or optical fungus. Spending $1000 on a defective lens, even if it is rare, is somewhat foolhardy (unless you are a collector, and have no plans to actually use the lens). It can be very challenging to have a rare lens repaired, depending of course on the type of damage – first it is hard to find someone to repair it, and it may also be hard and expensive to find parts (rare lenses means rare parts). For example I’ve seen one ad for a Konica Hexanon 57mm f/1.2, for C$500, cited the lens as being rare, with a series of caveats – internal spots of fungus on the optics, and stiff focus, and aperture mechanism. It turns out this lens is one of the least rare Hexanon lenses.

Note that some sellers use the term “rare find”, which is somewhat different in context. A rare find implies that there aren’t many available at a particular time.

P.S. Another term to be wary of is “mint”, which means pristine, or unblemished. Is it truly possible to define a lens as being devoid of all defects? Most vintage lenses contain contain at least some sort of dust internally (unless it was stored in its box in the right conditions for the past 50+ years).

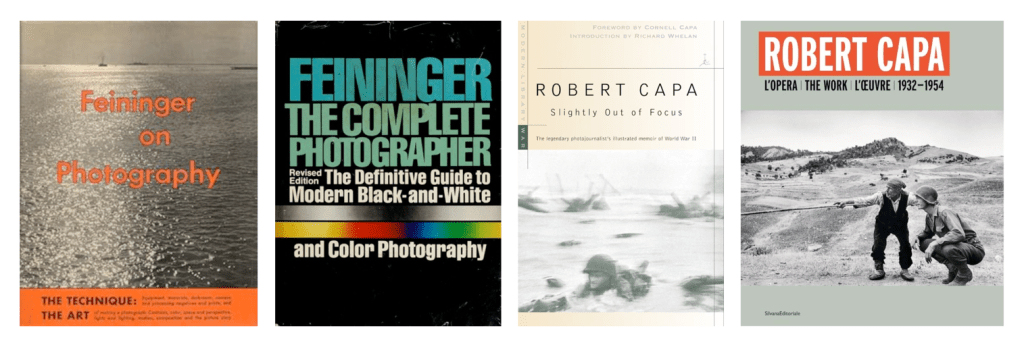

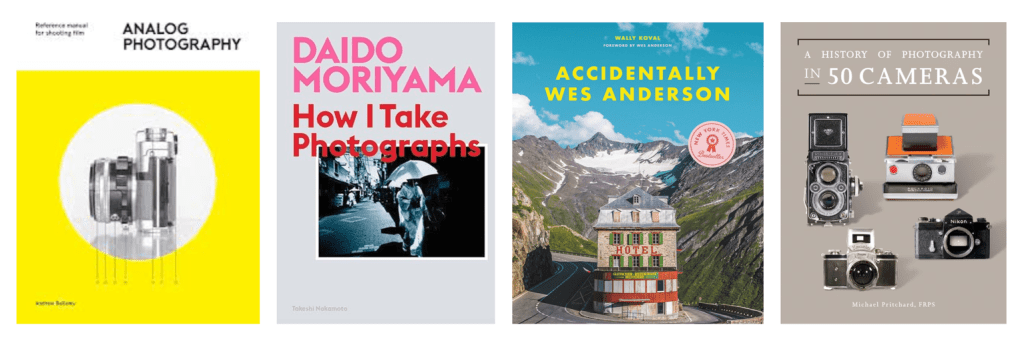

Photographic books for Christmas

If you know someone who dabbles in photography, and are looking for a Christmas gift, below are some book ideas. Some are new, others can be found on the vintage market, e.g. Abebooks.

- Any book by photographer Andreas Feininger. He produced a lot of really good books on photographic knowledge. Good ones include Feininger on Photography (1949), and The Complete Photographer (1965). Theses books are less about technology, and more about technique, much of which is just as relevant today in the age of digital.

- Robert Capa’s book, Slightly Out Of Focus: The Legendary Photojournalist’s Illustrated Memoir Of World War II (reprint 2001). A good insight into Hungarian photographer Robert Capa’s experiences during WW2 from the man himself.

- A deeper dive Capa’s photographs can be found in the more recently published Robert Capa: The Work 1932-1954 (2023).

- A very minimalistic approach to film photography can be found in Analog Photography: Reference Manual for Shooting, by Andrew Bellamy (2017). It dives into the fundamentals of 35mm film photography.

- In Daido Moriyama: How I Take Photographs (2019), Japanese street photographer Daido Moriyama explains his approach to street photography. A great book for anyone interested in getting a real insight into street photographer from one of the icons of the genre.

- A great coffee table book is Accidentally Wes Anderson (2020), photographs of real places plucked from the world of his films.

- For a vintage camera buff, there is a great little book, A History Of Photography In 50 Cameras (2022), which explores 180 years of photography through 50 iconic cameras.

Feininger on motion

In contrast to “moving pictures”, every single photograph, even the most violent action shot, is a “still”. Nothing that happens in time and space − a change, a motion − can be photographed instantaneously without stripping it of its most outstanding quality : movement, the element of time . . . . No ordinary action shot can “reproduce” an action, because it reduces change and movement − the basis of all action − to a standstill, freezing it into immobility. . . . In photographing action, more than anywhere else in still photography, we must rely on “symbols” and on “translation”, if we are to capture the essence of that action in a “still”.

Feininger on Photography (1949)

Zoomar – the first zoom lens for 35mm cameras

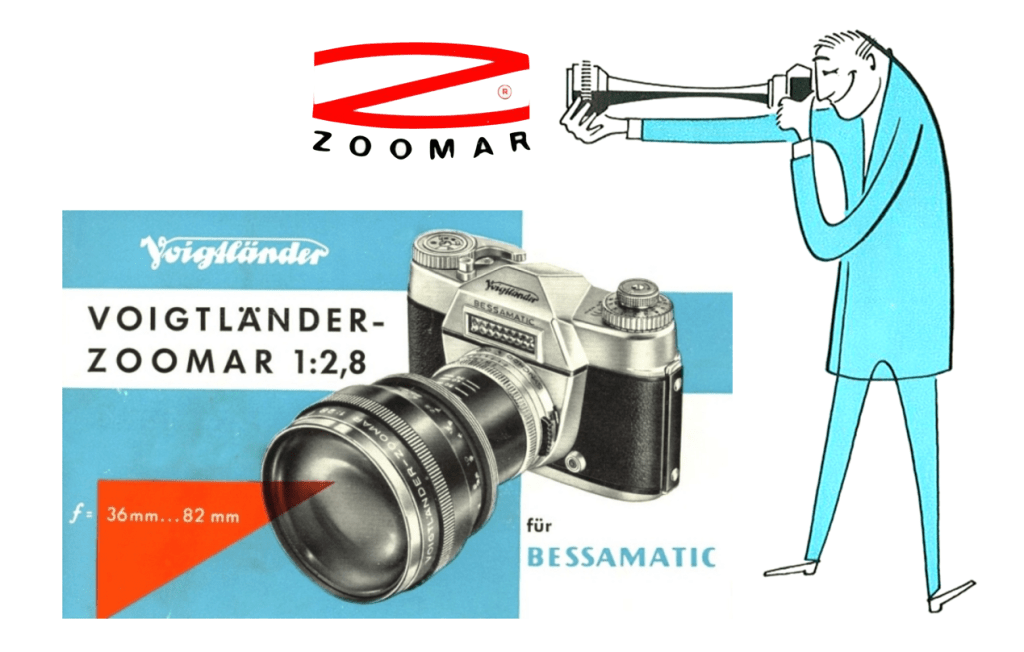

Historical accounts of who actually invented the zoom lens differ. But its adaptation to the SLR is down to one person – Frank Gerhard Back. He designed the first zoom lens for 35mm cameras – the Voightländer Zoomar. Before the Zoomar saw the light of day, designs with adjustable focal lengths were called varifocal lenses or rubber lenses.

“A great number of optical problems have been overcome in this lens. It is a splendid achievement. It zooms – what other still lens does?”

Look! A real zoom lens for your 35mm, Herbert Keppler, Modern Photography (May, 1959)

Back was born in Vienna, Austria in 1902. He attended the Technische Hochschule of Vienna where he received a masters in mechanical engineering in 1925, and a doctorate of science in 1931. From 1929 to 1938 he worked as a consulting engineer during which he was employed by Georg Wolfe, a manufacturer of endoscopes. In July 1939, he emigrated to the United States. After working for various companies in New York City, he started his own company in 1944, Research and Development Laboratory. In 1945 he started Zoomar Inc. where he developed and patented an optically-compensated zoom lens for 16mm television cameras (1948), and one for 35mm SLR cameras by 1959. From the late 1940s through to the 1970s, Back introduced new innovations for television, motion, picture, film photography, astronomical, and numerous other applications. On 25 October 1946, Back presented a new type of variable focal length lens to a convention of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers (SMPE) in Hollywood, California. The lens, sometimes known as the could zoom from 17 to 53mm, and contained 22 lens elements. It was 12” in length, weighed 790 grams and had an aperture range of f/2.9-f/22 [3].

Zoomar lenses disrupted the market for American television camera lenses, and likely were the catalyst in making zoom lenses ubiquitous in the industry. Back’s Zoomar lens had a substantial impact on both the motion picture, and television industries in the years following. It gradually made the “practice of “zooming” a more desirable, acceptable, and practical technique, in turn spurring demand for zoom lenses suitable for feature film use, with higher optical quality and greater zoom ranges. By 1954 a more compacts version of the “Zoomar 16” appeared – 5” in length, and weighing 570g it now had a zoom range of 25-75mm. It is not surprising that the concept would eventually spill over into the still camera industry.

In Back’s design, four of the lens’s 14 elements (the lenses in groups 2, 3, and 6 move linearly together to allow for focal length changes) move from 36mm to 82mm. A ×2.3 range from 36mm to 82mm allowed the lens to retain a reasonable speed of f/2.8, good image sharpness, and optical anomalies kept to a minimum (something earlier varifocal lenses could not achieve). The use of the word “zoom” likely derived from the Zoomar name. The lens used a push/pull mechanism to change focal length, whereby the change of focal length happens when the photographer moves the ring towards the mount or backwards.

Optically, the Zoomar 36-82 was a great breakthrough, made possible according to Dr. Back by new rare earth element glasses (Lanthanum) and computer aided optical designs. Back filed two patents in 1958 [6,7], one for optical design, and another for mechanics, likely at the same time production was already gearing up. Starting in 1959 the German optics firm Heinz Kilfitt would build the lens, under contract with Voigtländer for their Bessamatic SLR. The Voigtländer Zoomar was presented to the public on February 10, 1959 at the International Camera Show in Philadelphia (the same show that introduced the Nikon F and Canon Canonflex). Back would file another patent relating to an improved optical design in 1959 [8]. This optical design modified the rear lens elements, both in the type of element, and the material from which they were constructed.

By the late-1950s, Zoomar was to have some legal issues regarding its patent, fighting a patent battle with Paillard Products, the US subsidiary of Swiss company Paillard-Bolex, which had been importing French zoom lenses. In 1958 the New York Southern District Court ruled that Back’s patent overreached by appearing to cover all zoom lenses of any design. Zoomar eventually reduced its R&D of new lenses in favour of promoting foreign-made lenses – Back purchased Heinz Kilfitt in 1968 (catalog).

“The Voigtlander-Zoomar is the only Zoomar lens for still cameras. This model, with fully automatic diaphragm, is designed expressly for use with the Bessamatic Camera. A high-precision varifocal lens, in focus at all focal lengths from 36 to 82mm, it enables the photographer to shoot continuously at variable focal lengths without changing camera position.”

Description from the manufacturer.

The lens was produced from 1959-1968, with a total of only 15,000 units being built. Today the Zoomar 36-82 f/2.8 is often associated with the Voigtländer Bessamatic SLR. However the Zoomar was introduced from day one in both the DKL (Voigtländer) and Exakta mounts. Later it was also produced in other mounts, including the ALPA, and an M42 mount for the East German cameras like the Ikon Contax S. By the early 1960’s there were more zoom lens options, mostly in the telephoto zoom realm. None were anything special when compared to prime lenses, as they often had increased distortion and less contrast, but these were often overlooked because of the “newness” of the technology. It is still possible to find these lenses today, with prices in the range of C$700-1200 for lenses in reasonable condition.

✽ The Zoomar actually had a doppelganger – the Russian Zenit-6 camera came standard with a zoom lens called the Rubin-1. It wasn’t exactly the same, the focal length is shorter at 37-80mm and both had different zooming mechanisms.

Further reading:

- Hall, N., “Zoomar: Frank G. Back and the Postwar Television Zoom Lens”, Technology and Culture, 57(2), pp.353-379 (2016)

- Herbert Keppler, Bennett Sherman, “Zoom for you 35mm”, Modern Photography (May, 1959)

- Back, F.G., “The Zoomar Lens”, American Cinematographer, 28(3), p.87,109 (March, 1947)

- Back, F.G. et al., US Patent No.2,732,763, “Varifocal Lens Constructions and Devices”, assigned Jan.31, 1956

- Back, F.G., US Patent No.2,454,686, “Varifocal Lens for Cameras”, assigned Nov.23, 1948

- Back, F.G., US Patent No.2,913,957, “Varifocal Lens Assembly”, assigned Nov.24, 1959

- Back, F.G., US Patent No.2,902,901, “Reflex Camera Varifocal Lens”, assigned Sep.8, 1959

- Back, F.G., US Patent No.3,014,406, “Varifocal Lens Assembly for Still Camera Photography”, assigned Dec.26, 1961

- Roe, A.D., “The Zoomar Varifocal Lens For 16mm Cameras”, American Cinematographer, p.27,50 (January, 1954)

- Keppler’s Vault 94: The History of Zoom Lenses (2021)

Feininger on seeing

“Photographers — idiots, of which there are so many — say, ‘Oh, if only I had a Nikon or a Leica, I could make great photographs.”’ That’s the dumbest thing I ever heard in my life. It’s nothing but a matter of seeing, and thinking, and interest. That’s what makes a good photograph.”

Andreas Feininger in an interview with American Society of Media Photography (1990)