Vintage 35mm film cameras can survive for decades. You can pick up a camera from the 1960s and if its fully mechanical, there is a good chance it will still be fully functional. Vintage cameras that require batteries, e.g. for the exposure meter, or contain electronics are more of a hit and miss situation. The problem is that no one really can ascertain how well electronics age. Some age well, others don’t. Digital cameras are another thing altogether.

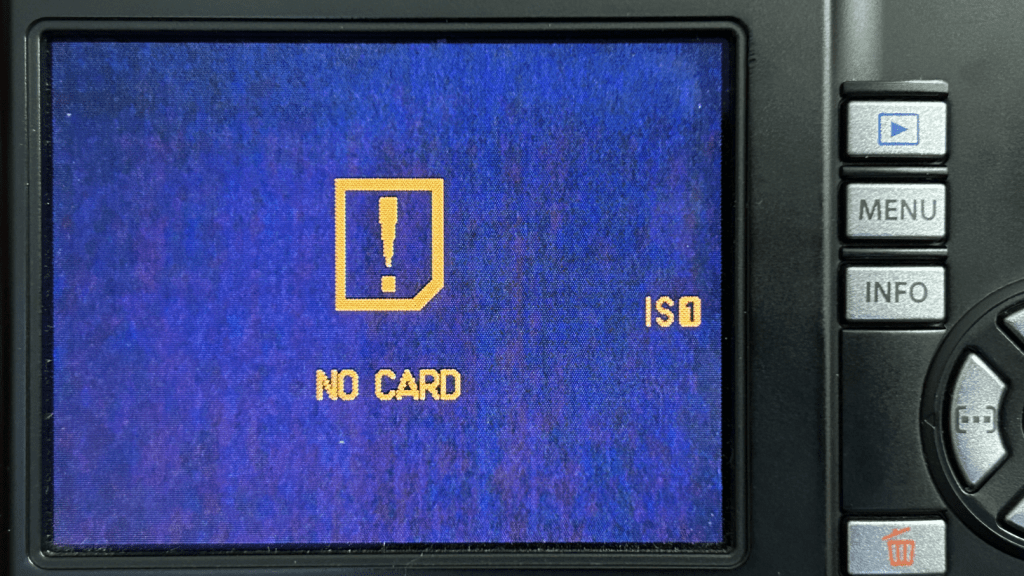

Anyone who has used digital cameras for the past 20 years likely has a few of these “zombie” cameras sitting in a cupboard somewhere. Cameras are upgraded, with their predecessors effectively “shelved”. The reality is that for the most part, digital cameras beyond a certain age just don’t hold much value (unless they are from Leica). One problem with vintage digital cameras is that things can just stop working. I have an old Olympus E-PL1 MFT camera. I haven’t used it in a while, and when I tried it today, it displayed a blinking red “IS-1” indicator. This basically means that the image stabilizer has failed (noticeable when the camera is first turned on because the anti-dust mechanism makes a rattling noise). That’s inherently an issue with electronics, things can just stop working, and fixing them on an old camera is often just not financially viable. It’s basically digital junk.

But the bigger problem is actually the battery. Some manufacturers have decided over the years to change the type of batteries used in their cameras (for many reasons). When a camera becomes legacy, i.e. is no longer supported, there is a good chance that the manufacturer will stop making the associated batteries. The E-PL1 was introduced in 2010, and although the battery in my camera still works, it is not possible to buy Olympus BLS-1 batteries for it anymore. It is also not really possible to determine what the status of existing batteries is – measuring the number of battery cycles is not easy or even possible (unlike laptop batteries). One way is to charge the battery, and take photographs until it drains, but tedious is an understatement. A battery will typically last between 300-500 recharge cycles.

The result is a vintage digital camera that may still work well, but ultimately needs a new battery. You could try the gambit of 3rd party batteries, but there really isn’t any way of knowing what battery will actually work, because they don’t usually come from verifiable battery makers (often resulting in slight fluctuations in the voltage provided to the camera). Yes, you can get replacement batteries from companies like Duracell (via DuracellDirect.com), however this company is not owned by Duracell, but rather PSA Parts Ltd. And these batteries are not exact replacements. For a real analysis, check out this article by Reinhard Wagner who dissects some off-brand Olympus BLN-1 batteries (it’s in German, but is easy to translate).

So what does this mean? Essentially if you want to use a camera long-term, make sure you have a good amount of spare batteries, i.e. anyways purchase at least one spare battery when purchasing a new camera. Also check the date on the batteries, as they made need replacing as they age. In all likelihood, nobody is going to be using vintage digital cameras in 50 years time, but they still might be using film ones.

P.S. The digital “age” of a camera is sometimes counted using the idea of “shutter actuation’s“. This is basically a count of how many photos have been taken. A modern mirrorless camera will have shutters rated at around 100-150K. Most cameras likely won’t come anywhere near that count, so they aren’t really a valid notion, except perhaps to indicate how much a camera has been used.