One of the more interesting aspects of photographing outdoors is the colour of the sky. You know the situation – you’re out photographing and the sky just isn’t as vivid as you wished it was. This happens a lot in the warmer months of the year.

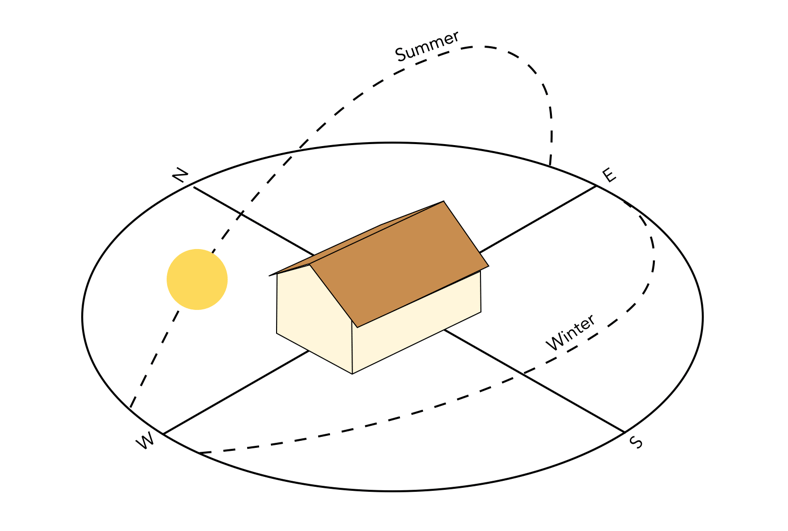

The sky isn’t blue of course. We interpret it is blue because of light, and its interaction with the atmosphere. The type of blue also changes, but the difference is most noticeable in fall and winter, when the sky appears a more vivid blue than it does throughout the summer months (that’s why you can never expect a really vividly blue sky in summer when travelling).

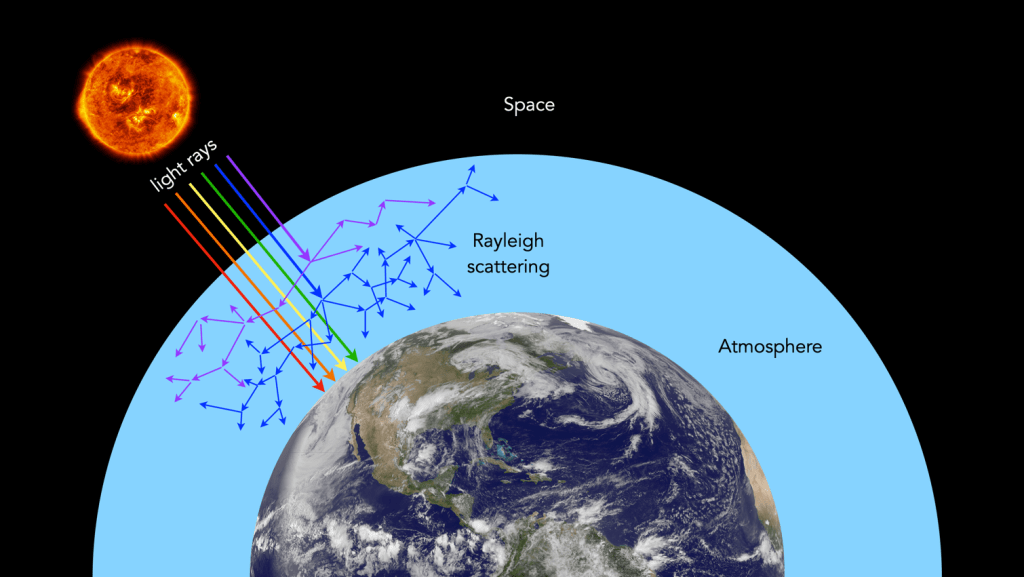

Firstly the blue colour of the sky is due to the scattering of sunlight off molecules in the atmosphere smaller than the wavelength of light (approximately 1/10th the wavelength). There are many gases in the atmosphere, e.g. nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen. Mixed in with these elements are particles which include dust, pollen, and pollution. The scattering is known as Rayleigh scattering, and is most effective at the short wavelength (400nm) end of the visible spectrum. Therefore the light scattered down to the earth at a large angle with respect to the direction of the sun’s light is predominantly in the blue end of the spectrum. Because of this wavelength-selective scattering, more blue light diffuses throughout atmosphere than other colours producing the familiar blue sky.

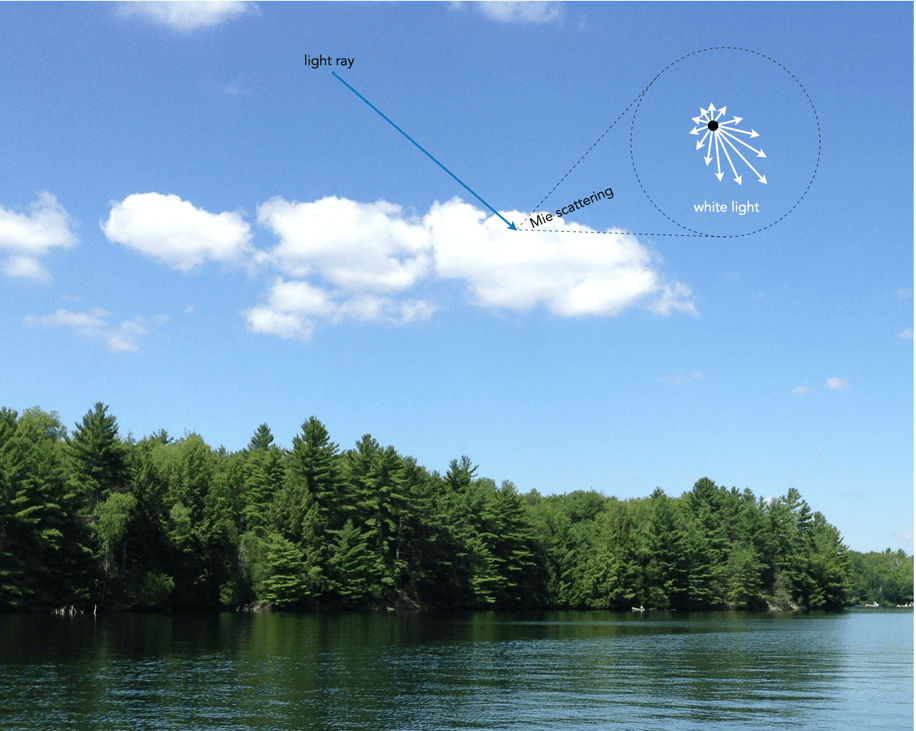

During the summer months, when the sun is higher in the sky, light does not have to travel as far through the atmosphere to reach our eyes. Consequently, there is less Rayleigh scattering. Blue skies often appear somewhat hazy, veiled by a thin white sheen. When light encounters large particles suspended in the air, like dust or water vapour droplets, wavelengths are scattered equally. This process is known as Mie scattering, and produces white-coloured light, e.g. making clouds appear white. In summer in particular, increased humidity increases Mie scattering, and as a result the sky tends to be relatively muted, or pale blue.

In the fall and winter the Northern Hemisphere is tilted away from the sun, the sun’s angle is lower, which increases the amount of Raleigh scattering (light has to travel further through the atmosphere, and the scattering of shorter wavelengths is more complete). The cooler air during this period also decreases the amount of moisture the air can hold, diminishing Mie scattering. These two factors taken in conjunction can produce skies that are vividly blue.

Q: If the wavelength of purple is only 380nm, why don’t we see more purple skies?

A: Purple skies are rare because the sun emits a higher concentration of blue light waves in comparison to violet. Furthermore, our eyes are more sensitive to blue rather than violet meaning to us the sky appears blue.

Q: What particles cause Rayleigh Scattering?

A: Small specks of dust or nitrogen and oxygen molecules.