Experienced photographers and camera manufacturers often talk about weather-sealing. But what is it?

Weather-sealing is a term used to convey that there is a protective layer that helps block out things that are harmful to the electronics of a camera (or the internal workings of a lens) – things like dust, water, snow, and humidity. Whether a camera has weather-sealing or not, and how much weather sealing is dependent on the particular manufacturer. Typically the more expensive a camera, the greater the chance of weather sealing. Weather sealing consists of gaskets, and perhaps a lining made from rubber or silicon. This is particularly important in regions such as the lens mount, and any moving parts.

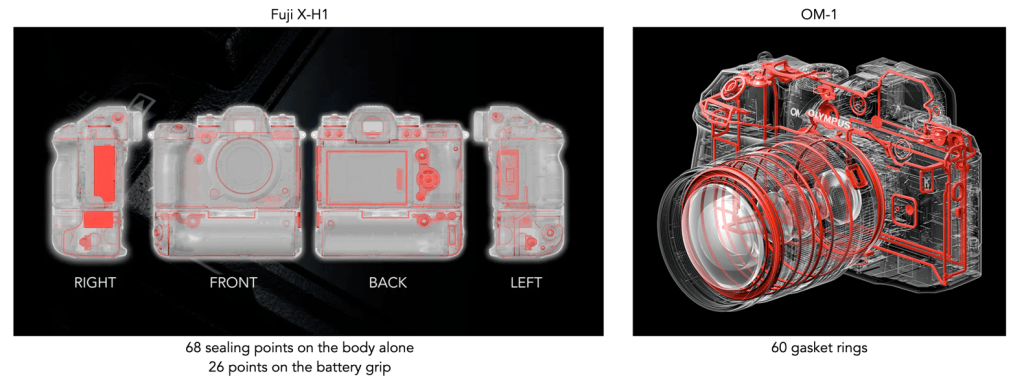

Weather sealing is challenging, partially because there are seams everywhere – between panels on the body and the battery and card compartments, the various controls like switches, push-buttons, rotating knobs and dials. Any break in continuity offers an opportunity for water to seep in. Larger components are the easiest to seal, often achieved using a gasket of some form, e.g. foam, rubber, between adjacent panels. Smaller controls also have foam or rubber gaskets, or O-rings where they interact with the camera body. Consider the Fuji X-H1 as an example (Figure 1). Fuji explained the weather sealing in “X-H1 Development Story #3”. They describe it as having a total of 68 sealing points on the body alone, and additional 26 sealing points for the battery grip. The X-H1 has rubber gaskets all over the body. The memory card door is locked firmly in place with a lock switch and the door has rubber seals to prevent moisture seeping into the compartment. Even the buttons and the joystick have rubber seals around to prevent moisture and dust from getting into the camera.

But weather-sealing is not the same as being water resistant, or waterproof. Weather sealing means a camera can withstand a few small droplets of moisture, or perhaps foggy environs, but it does not mean it one can sit out in a rainstorm. A waterproof camera on the other hand is one which can be fully submerged. Weather sealing also does not prevent condensation. This could only be prevented by filling the camera (and lens) with some inert gas, and sealing it completely. The sheer act of changing lenses allows air inside, and if moving from a warmer or cooler environment too quickly there is a risk of condensation forming. What does weather-sealing really mean? It’s honestly a bit like the terms used on outdoor gear like raincoats, i.e. somewhat vague. Ads for weather-sealing can be a bit bemusing. For example in the ad for the Olympus OM-D EM-5 Mark III, there is a camera sitting in a rainstorm with water splashing around it (Figure 2) – practical? I think not.

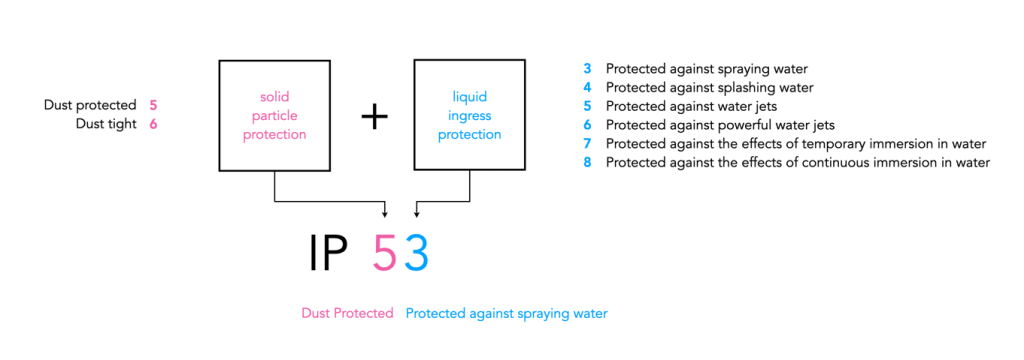

There is no real standardized means of rating weather sealing on cameras, however there is a system known as the IP or “Ingress Protection” rating and it is the standard that rates devices on their sealing properties. The IP rating is commonly used for smartphones, and security cameras. For example many recent iPhone’s have an IP rating of IP68. Notice the two digits, IP68? The first digit “6” indicates indicates the level of resistance and protection to harmful dust. The second digit “8” indicates the level of resistance to water. A rating of “8” means “protected from immersion in water with a depth of more than one meter.” These phones are well protected against dust and are also water-resistant but not fully waterproof.

One of the few digital cameras to get an IP rating, the OM-1 Mark II (formerly Olympus) has a rating of IP-53. This rating provides the second-highest level of dust protection that exists (partial protection against dust that may harm equipment) and certifies that the camera can continue to operate with water falling as a spray onto it at an angle of up to 60°. This means the camera can withstand most weather phenomena, and work in temperatures as low as -10°C. The OM System M.Zuiko 12-40mm f/2.8 Pro II lens (2022) has the same rating. The camera in the rainstorm, the OM-D EM-5 Mark III had an IPX1 rating, meaning it is water resistant to some extent, i.e. protected against vertically falling drops of water (which did not exactly make it splashproof, as IPX1 is the lowest level of protection against liquids). A step above IP-53 is the Leica SL3 with a rating of IP-54 which means the camera is protected from water spray from any direction.

The biggest question is does a camera need weather sealing? The answer is based on whether or not a photograph engages in activities where dust and moisture become an issue. This includes travel to places that are susceptible to inclement, or “four seasons in one day” type weather. Weather sealing is somewhat of an insurance policy, but isn’t necessary for most photographers. It is also better at keeping out dust than moisture. The reality is that most camera manufacturers don’t actually designate an IP rating for their cameras – that’s not to say cameras aren’t well protected against the elements. And terms like splashproof, and weather resistance are really not that useful if they aren’t definable (e.g. in terms of IP ratings), otherwise you have to ask – how resistant?

So how does one deal with weather if you are in photographing in places with inclement weather? Firstly, store the camera gear in a waterproof bag. Avoid sand – it is not the same thing as dust. Also avoid salt water, it does not behave in the same way as fresh water – salt is everyone’s enemy. If shooting in a place like Iceland, where rain is always a possibility, use a rain and dust covers. Sleeves like the Op/Tech Rainsleeve are inexpensive and easy to carry (the Original sells for about C$15 for a pack of two). Another option is a shell from Peak Design which sells for about C$65 (medium). Something that is certainly taboo is changing a lens in rainy or windy conditions – it might be one of the worst things that can be done to a camera.

Want to see how weather sealing works? Check out this article by Dave Etchells [6] who delves into the intricacies of weather sealing technology at Olympus. He investigates both cameras and lenses, with photos of the weather sealing inside the camera (from Olympus R&D).He has also tested the Fuji X-T3 [4], the Canon EOS R [7], and Nikon Z6/Z7 [8]. There is also a great article on PetaPixel [9], that explores the various ways OM (formerly Olympus) tests its cameras (arguably one of the best testing environments around).

Further reading:

- Fuji, “Weather resistant technology” (2015)

- Jeff Carter, “Out in All Weathers”, FujiLove (2018)

- Chris Gampat, “Watch the Not Weather-sealed FujiFilm XS10 Survive being Frozen”, The Phoblographer (2020)

- Dave Etchells, “Fuji X-T3 Weather-Resistance Test Results”, Imaging Resource (2019)

- What nobody told you about Fujifilm weather sealing.

- Dave Etchells, “How to REALLY weather-seal a camera. We go deep behind the scenes at Olympus R&D headquarters”, Imaging Resource (2020)

- Dave Etchells, “Canon EOS R Weather-Resistance Test Results”, Imaging Resource (2019)

- Dave Etchells, “Nikon Z6 / Nikon Z7 Weather-Resistance Test Results”, Imaging Resource (2019)

- Jaron Schneider, “How OM Digital Torture Tests its Weatherproof Cameras”, PetaPixel (2022)

- Chris Gampat, “No, Your Camera is not Waterproof. It’s Protected, Maybe.”, The Phoblographer (2022)

- Mac, “Peak Design Shell Camera Cover Review”, Halfway Anywhere (2023)