Zunow was a lens maker who dabbled in camera making. Their biggest claim to fame is arguably that they were the first to introduce an ultrafast 50mm lens for rangefinder cameras. Supposedly the meaning of Zunow derived from the Japanese word zunō meaning “brain” (although there was also a Zunow company producing bikes where it meant “genius”).

Suzuki Sakuta founded Teikoku Kōgaku Kenkyūjo (Imperial Optical Research Institute) circa 1930 and worked for other companies grinding lenses. In 1954, the company changed names to Teikoku Kogaku Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha (Teikoku Optical Industry Corporation), and in 1956 it became Zunow Kōgaku Kōgyō K.K., or Zunow Optical Industry Co. Ltd..

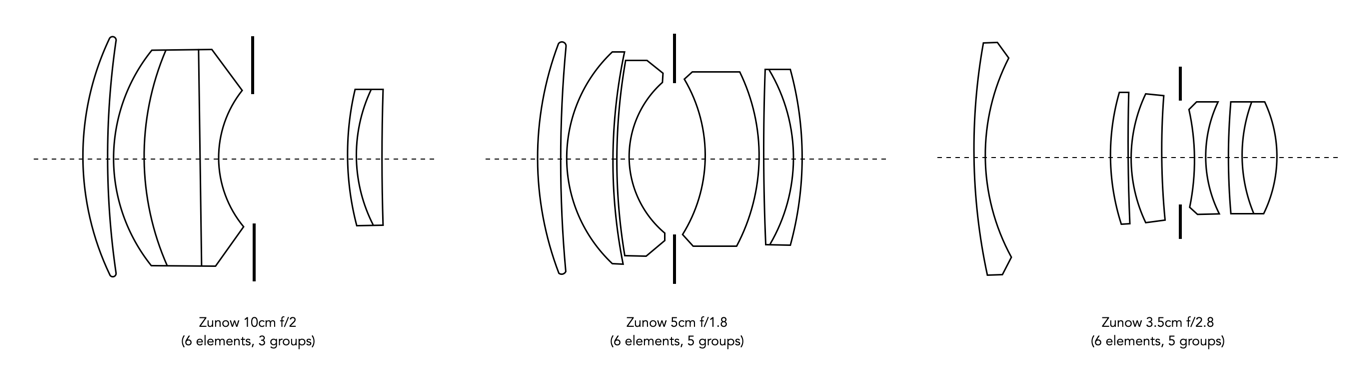

Zunow made a number of lenses for both rangefinder and SLR cameras, including slower 50mm lenses in f/1.3, and f/1.9, a 35mm f/1.7, and a 100mm f/2 lens. In 1953 they introduced a 5cm f/1.1 lens for rangefinder cameras, which at the time was the fastest lens available for any 35mm camera. The f/1.1 lens was not matched in speed until Nippon Kogaku introduced the Nikkor 50mm 1.1 in 1956. After this they started making lenses for other manufacturers, which weren’t as fast, but they were good quality lenses. For example the 35mm f/1.7 was a smidgen faster than the Nikkor 35mm f/1.8. The lenses were often used by other manufacturers as standard lenses. A good example is the Miranda T which came standard with a Zunow 50mm f/1.9 lens. There is some supposition that Zunow supplied the 5.8cm f/1.7 lens for the Yashica Pentamatic II when it appeared in 1960 [1].

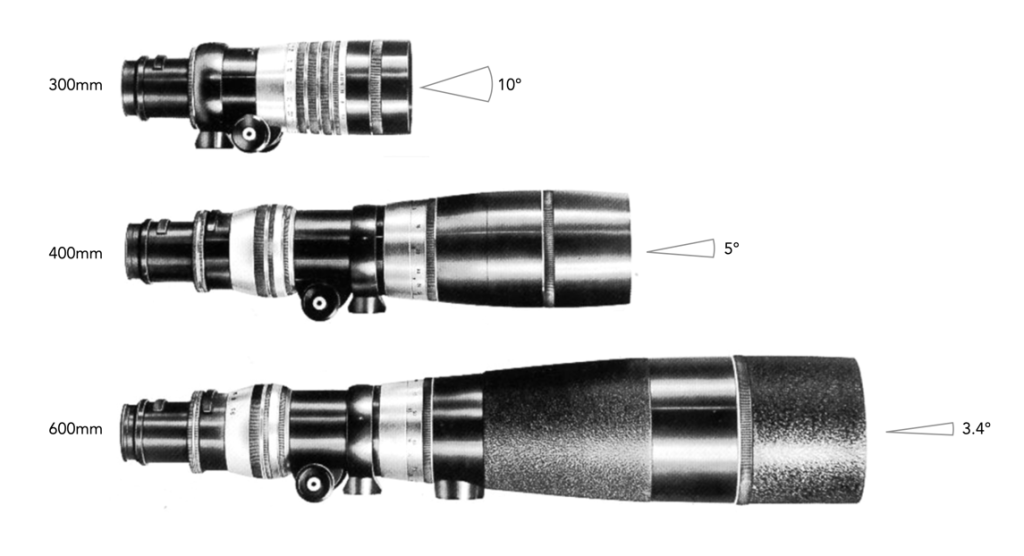

The first cine lens was a 5cm f/1.1 lens produced for American motion picture camera company Mitchell. The company also produced Zunow-Elmo Cine f/1.1 lenses for D-mount (8mm) in 13mm, 25mm, 38mm; and C-mount (16mm) 25mm, 38mm and 50mm.

The decline of Zunow was precipitated by the failure of its Zunow SLR in 1959, and by the bankruptcy of two of its customers – Arco in late 1960 and Neoca in January 1960. Zunow’s financial situation worsened, and rather than become a subsidiary of another company, the company was closed in 1961 [2]. In the same year, Suzuki Takeo founded a new company in partnership with Elmo (who Zunow had supplied lenses for) called Ace Optical who continued making lenses for 8mm and 16mm cine cameras, as well as other commercial lenses [2].

Besides the 5cm f/1.1, other lenses are available, especially in the Japanese market. The cine lenses seem to sell anywhere from US$200-1000. The 3.5cm f/1.7 rangefinder (L39) lens has sold for around US$3500. Typically they are found mostly on the Japanese market.

A list of lenses produced in 1957:

- Rangefinders (Leica IIIf and M-3, Contax Canon, Nikon) : 35mm f/1.7, 50mm f/1.1, 50mm f/1.3, 50mm f/1.9, 100mm f/2.

- 35mm SLR : 50mm f/1.9, 100mm f/2

- 8mm cine : f/1.1 – 13mm, 25mm, 38mm

- 16mm cine : f/1.1 – 25mm, 38mm, 50mm

Company name timeline:

1930 − Teikoku Kōgaku Kenkyūjo (Imperial Optical Research Institute)

1954 − Teikoku Kogaku Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha or Teikoku Optical Industry Corporation

1956 − Zunow Kōgaku Kōgyō K.K., or Zunow Optical Industry Co., Ltd.

1961 − Company closes, re-envisioned as Ace Optical the same year

Notable lenses: Zunow 5cm f/1.1 (1953)

Note that there is still an unrelated company called Zunow in the north of Japan, which makes conversion lenses and filters (for cine cameras).

Further reading

- Was this beautiful lens, which was made exclusively for the Pentamatic II designed by Zunow Optical?, Chasing Classic Cameras with Chris (2017)

- Interview with Suzuki Takeo, CEO of Ace Optical (son of Zunow’s president), May 2006