If it were not for one particular point in time, Kilfitt may not be as well known a brand as it is. That event was the use of the Kilfitt Fern-Kilar f/5.6 400mm lens in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1954 movie “Rear Window”, where the lens, as well as the Exakta camera it was attached to, played a prominent role in the movie (in fact no other camera/lens combination likely ever had such a leading role).

Kilfitt was one of the most innovative lens makers of the 1950s. Born in Westphalia in 1898, Heinz Kilfitt had quite a pedigree for design. Before the war he had established his reputation designing the Robot I camera (24×24mm format), the first motorized camera, introduced in 1934. Rejected by Agfa and Kodak, Kilfitt partnered with Hans-Heinrich Berning to develop the camera. In 1939 Kilfitt sold his interests in the Robot to Berning. In Munich, Kilfitt acquired a small optical company, Werkstätte für Präzisionsoptik und Mechanik GmbH, where he began developing lenses for the like of 35mm systems.

By the end of the war in 1945 Kilfitt had very little left, basically a run-down plant, and few workers. He started a camera repair shop for US army personnel, and by 1948 had started to manufacture precision lenses. Kilfitt devoted himself to what he considered an inherent problem with the photographic industry – the lack of lens mount universality. Every camera had to have its own set of lenses. This led him to introduce the “basic lens” system in 1949. In this system, each lens was supplied with a “short mount”, the rear of which had a male thread which accommodated a series of adapters [1]. Some for SLR, some for C-mount, or reflex housings.

While the company is famous for its telephoto lenses, it actually specialized in another area: macro. Early SLR lenses such as the Biotar 58mm f/2 were able to focus as close as 18 inches, which likely seemed quite amazing, considering the best a rangefinder could do was 60-100cm. Kilfitt thought he could do better, producing the world’s first 35mm macro lens, the 40mm f/2.8 Makro-Kilar in 1955 [3]. It would be what Norman Rothschild called the first “infinity-to-gnats’-eyeball” [2]. It was offered in two versions: one that focuses from ∞ to 10cm, with a reproduction of 1:2, and one that focused from ∞ to 5cm, with 1:1.

Heinz Kilfitt also continued developing cameras. The Kilfitt-Reflex 6×6 appeared around 1952, a camera that had a new system for quickly changing lenses, a complex viewfinder and a swing-back mirror. It influenced the design of other 6×6 format cameras, e.g. Kowa 6. There was also the Mecaflex SLR, another 24×24mm camera produced from 1953-1958 (first by Metz Apparatefabrik, Fürth, Germany later by S.E.R.A.O. Monaco). It was constructed by Heinz Kilfitt, who also supplied the lenses (Kilfitt Kamerabau, Vaduz, Liechtenstein).

| Lens | Smallest aperture | AOV | Shortest focus | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40mm Makro-Kilar f/2.8 | f/22 | 54° | 2-4″ | 150g |

| 90mm Makro-Kilar f/2.8 | f/22 | 28° | 8″ | 480g |

| 135mm KILAR f/3.8 | f/32 | 18° | 60″ | 260g |

| 150mm KILAR f/3.5 | f/22 | 16° | 60″ | 400g |

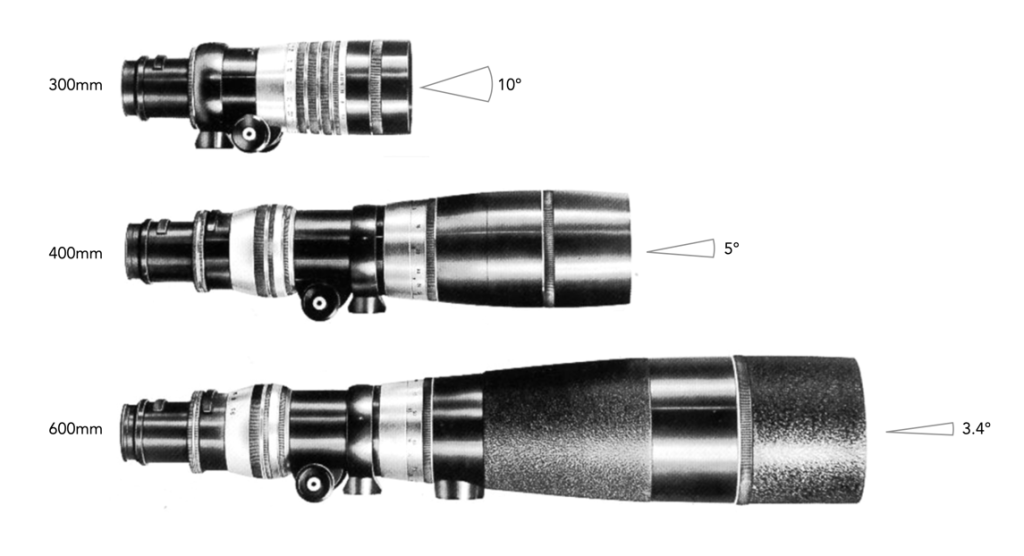

| 300mm TELE-KILAR f/5.6 | f/32 | 8° | 120″ | 990g |

| 300mm PAN-TELE-KILAR f/4 | f/32 | 8° | 66″ | 1930g |

| 400mm FERN-KILAR f/4 | f/45 | 6° | 30′ | 1760g |

| 400mm SPORT-FERN-KILAR f/4 | f/45 | 6° | 16′ | 2720g |

| 600mm SPORT-FERN-KILAR f/5.6 | f/45 | 4° | 35′ | 4080g |

When Heinz Kilfitt retired in 1968 he sold the company to Dr. Back, who operated it under the Zoomar name from its headquarters in Long Island, New York. Dr. Back designed the first production 35mm SLR zoom, the famous 36-82/2.8 Zoomar in 1959. The company eventually transitioned the brand to Zoomar-Kilfitt, and then merged it completely into Zoomar. By this stage the company was providing lenses for 12.84×17.12mm, 24×36mm and 56×56mm cameras. The most notable addition to the line-up was a Macro Zoomar 50-125mm f/4.

Note that the Zoomar lenses are often cited as products of Kilfitt, however although some of them may have been produced in the Kilfitt factories, Zoomar was its own entity. Kilfitt was contracted to manufacture the groundbreaking 1960 Zoomar 36-82mm lens for Voigtländer.

Notable lenses: FERN-KILAR 400mm f/4, Makro-Kilar 40mm f/2.8

Further reading:

- Norman Rothschild, “An updated view of the Kilfitt system”, The Camera Craftsman, 10(2), pp.10-15 (1964)

- Norman Rothschild, “The revolution in SLR lenses”, Popular Photography, (60(6), pp.90-91,130-131 (1967)

- Berkowitz, G., “New.. Makro Kilar Lens”, Popular Photography, pp.86-87,106,108 (Mar, 1955)

- Kilfitt Optik, Photo But More

- ROBOT – Who came up with the idea? Kilfitt or Berning? Two genealogists come together to new discoveries…, fotosaurier (2021) article in German