In the days of film cameras, every company had it’s own way of “naming” cameras and lenses. This made it very easy to identify a lens. Asahi Pentax had the ubiquitous Takumar (TA-KOO-MA) name associated with its 35mm SLR and 6×7 lenses. The name would adorn the lenses from the period of the Asahiflex cameras with their M37 mount, through the M42 mount until 1975 when the switch to K-mount came with a change to the lens branding.

Asahi was founded by in 1919 by Kumao Kajiwara as Asahi Optical Joint Stock Co. Asahi began making film projection lenses in 1923, and by the early 1930s was producing camera lenses for the likes of future companies Minolta (1932), and Konica (1933). In 1937 with the installation of a military government in Japan, Asahi’s operations came under government control. By this time Kajiwara had passed away (it is not clear exactly when), and the business passed to his nephew Saburo Matsumoto (possibly 1936?). It was Matsumoto who had the vision of producing a compact reflex camera. In 1938 he bought a small factory in Tokyo and renamed it as Asahi Optical Co. Ltd.

It seems as though the lens series was named in honour of one of the founders brother, Takuma Kajiwara. There might have been the analogy that photography was a means of painting with light, and lenses were like an artists brushes. On a side note, the name Takuma in Japanese is an amalgam of “taku” meaning “expand, open, support”, and “ma” meaning “real, genuine”.

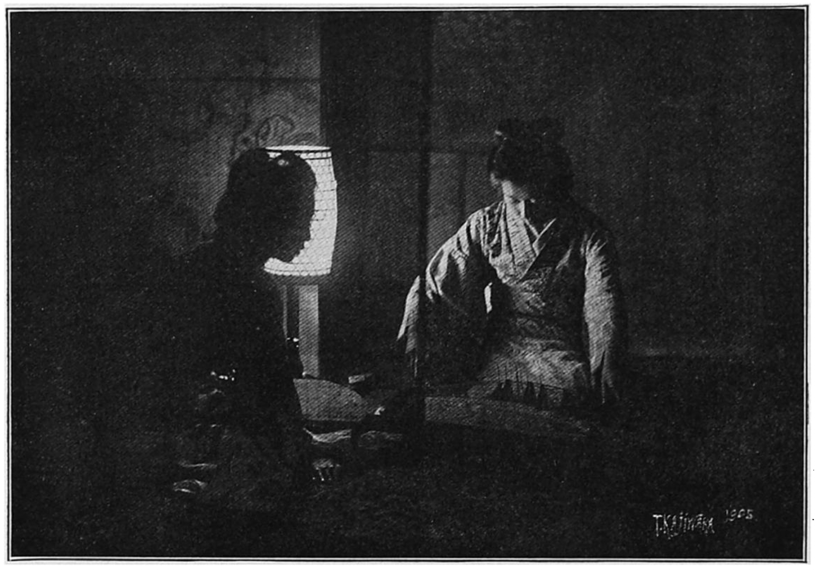

Takuma Kajiwara (1876-1960) was a Japanese-American photographic artist and painter who specialize d in portraits. Born in Kyushi, Japan he was the third of five brothers in a Samurai family. Emigrating to America at the age of 17, he settled in Seattle, and became a photographer. He later moved to St.Louis and opened a portrait studio, turning from photography to painting. In 1935 he moved to New York. In 1951 he won the gold medal of honour for oils from the Allied Artists of America for his expressionist painting of the Garden of Eden titled “It All Happened in Six Days”. Takuma himself had an interest in cameras, patenting a camera in 1915 (Patent No. US1193392).

Note that it is really hard to determine the exact story due to the lack of accessible information.