Many smartphones are now marketed as having at least one camera with a ridiculous amount of megapixels. The iPhone 14 Pro has 48MP, the Samsung Galaxy S23 has 200MP. Is it just too much? The answers is yes, and some would argue it’s more of a marketing hype than anything else. I mean who doesn’t want to take a 48MP or 200MP image? Well, most people may try it once, but many won’t routinely use it, and the reasons why are varied. First, let’s look at the technology.

Smartphone sensors are no different to any other sensors, they are just usually smaller than many conventional digital camera sensors. The sensors contain a bunch of photosites, so no different there. But there are limits to the size of sensor that can be used inside a smartphone, made more restrictive by the fact that many smartphones now have 2-3 rear-facing cameras. Higher resolution means that more photosites need to be crammed into the sensor’s surface area. The iPhone 14 Pro has a wide angle camera with a 48MP resolution. It uses a 1/1.28” sensor, which is 10×7.5mm in size with a photosite pitch of 1.22µm, which is extremely small. Typically smaller pixels have a harder time getting light than larger ones, leading to some issues in low-light situations. So smartphones typically get around this by creating reduced resolution images with “bigger” pixels that are created by means of photosite binning (or pixel binning if you like).

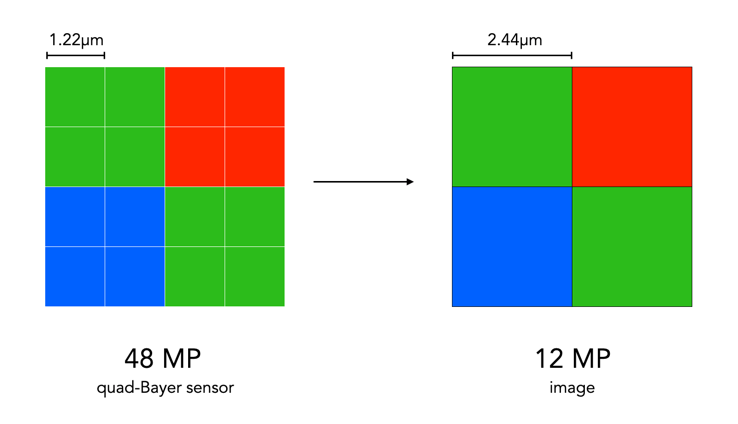

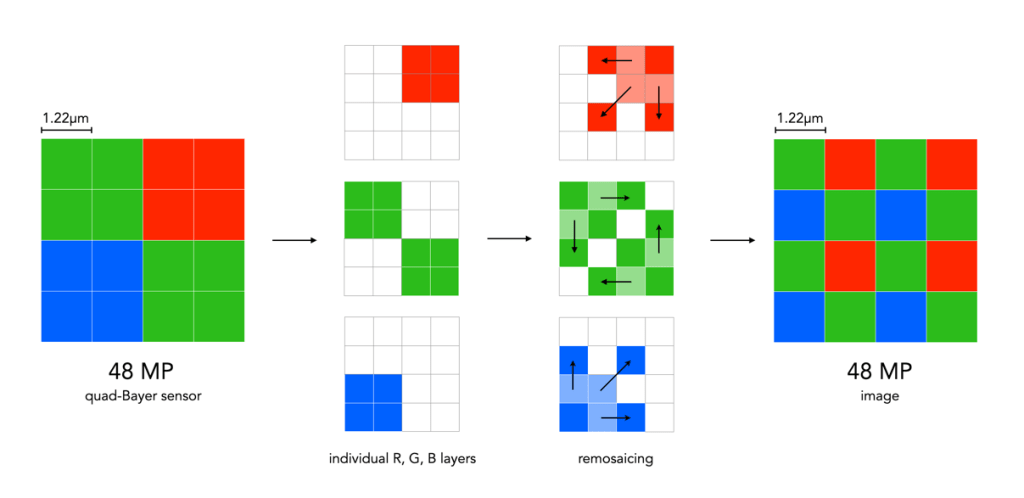

Photosite binning artificially groups smaller pixels into larger ones, potentially boosting the amount of light that can be gathered. The example in Figure 1 shows part of the quad-Bayer sensor of the iPhone 14 Pro. It illustrates how a 12MP is generated from a 48MP sensor. Here four photosites (2×2) are binned from the sensor, producing a 12 megapixel image, i.e. 48÷4=12. The Samsung Galaxy S22 Ultra takes 108MP images, and also defaults to 12MP, but instead of using a 2×2 binning, it uses what Samsung calls “Nonacell” technology”, merging 3×3 photosites into a super pixel. So the photosites, which have a pitch of 0.8µm, are merged to form a 2.4µm super-pixel. Figure 2 shows how a true 48MP images is create via some sort of remosaicing algorithm (pixel rearrangement algorithm).

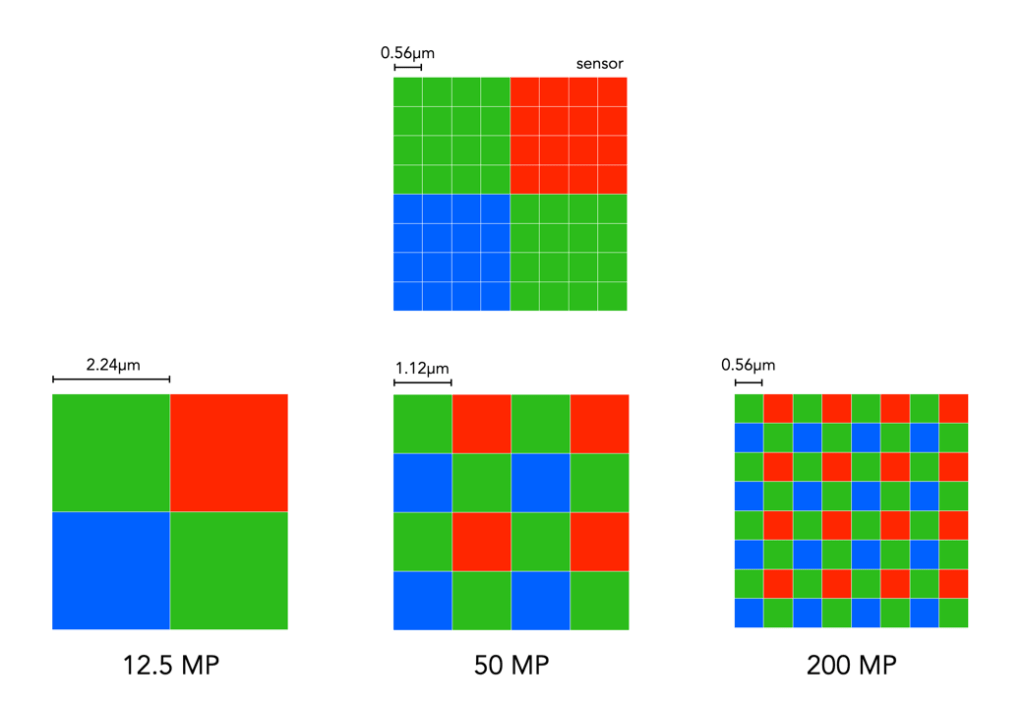

The 200MP Samsung ISOCELL HP-3 1/1.14” sensor takes it a step further. It uses a new “Tetra2” binning mechanism, with 0.56µm photosites. It can produce 200MP, 50MP, and 12.5MP images (shown in Figure 3). In the first stage 2×2 binning is used on the sensors 0.56µm photosites, producing a 1.12µm “super-photosite”, and a 50MP image. Then another round of 2×2 binning is performed, creating a 2.24µm “super-super-photosite”, and a 12.5MP image.

These high resolution sensors are typically only used at full-resolution in bright scenes, reducing to a lower resolution in dark conditions. The idea of binning is to allow smartphone cameras to become more intelligent, choosing the optimal resolution based on the photographic conditions. Of course the question is, does anyone need 50 or 200MP images? As with all technology, there are drawbacks.

Firstly, in the world of digital cameras, 100MP or thereabouts is usually found on a medium format camera with a sensor size of about 44×33mm, e.g. Fujifilm GFX 100S. These cameras are designed to take high resolution images, with sensors containing photosites of a reasonable light-gathering size (e.g. 3.76µm). Now compare the photosite area of this medium format camera, at 14µm2, with that of the Samsung Galaxy S22 at 0.64µm2 – 22 times more light gathering surface area. There is no comparison. Digital cameras also generally use high-quality lenses, with a lot more light gathering potential than those found on smartphones – when it comes to optics, smaller is always marred in compromises.

The process of binning pixels may also introduce artifacts, whether it be a small change in the overall colour of the image, or perhaps blurring artifacts – it really depends on the technology, algorithms, etc. Even remosaicing is a little more challenging, primarily because the different colours are further apart. So there isn’t really 4× more detail in 48MP mode than there is in 12MP mode. Then there is storage. 200MP image files should be large, but due to some sort of compression wizardry, the 12240×16320 images are reduced to files about 30MB in size, which is quite reasonable. Supposedly RAW (DNG) images can take up to 120MB. So storage is an issue. Also, what do you really need a 200MP camera for?

So if the mainstay is a quasi-12 megapixels why do manufacturers waste effort in creating hyper-megapixel smartphones? Perhaps for that one ideal 200MP shot? That perfect sunset while on vacation in Iceland. But what would you do with a 200MP image? Make a print to hang up on the wall? More megapixels does allow for better digital zooming, but the more likely case is that manufacturers know that megapixels matter to consumers, a situation they themselves have hyped up over the past two decades.

Further reading:

Quad Bayer sensors: what they are and what they are not (2019)