Trying to choose between a zoom and a prime lens can be challenging, mainly because they probably shouldn’t be compared in the first place. Basically they offer different outcomes. A prime is almost a lens specialized for a particular task, whereas a zoom can be more of a “jack-of-all-trades”. There are also different types of each of these lenses. There are expensive fast primes, and less-expensive primes with a slower maximum aperture. There are also native primes from the camera manufacturer, and third-party primes. The same criteria can be applied to zoom lenses. Table 1 summarizes some of the key differences between prime and zoom lenses.

| characteristic | prime | zoom |

|---|---|---|

| price | + simple build, less expensive | − complex build, more expensive |

| aperture | + brighter, wider aperture (faster) e.g. f/1.2 to f/2 | − darker, narrower aperture (slower) |

| sharpness | + sharper images, fewer optical deficiencies | − less sharpness, some distortion |

| versatility | − less versatile | + more versatile |

| size and weight | + lighter and more compact − have to carry more lenses | − bulkier and heavier + need to carry fewer lenses |

A zoom provides a level of flexibility that a prime does not, but this comes with some trade-offs. The first thing a zoom lens typically gives up is speed, i.e. how wide the aperture opens up. Prime lenses on the other hand are fast, and some are super-fast. Note that prime lenses are nearly always smaller and lighter than zooms. Many things influence the size and weight of a lens including whether it is a pro-grade lens (often contain more glass), or whether it has a large maximum aperture (again requiring a bigger lens with more glass). Every lens has its pros and cons.

Despite the fact that prime lenses are often lauded for their specific nature, i.e. suited to one particular task, zoom lenses can also be categorized in this manner. For example someone might choose a 17-28mm full-frame lens for landscapes, providing some scope. In addition, although a good zoom lens may be more expensive than a prime, more prime lenses may be needed to equal the range of coverage, thereby leading to more cost. There are also some lenses that don’t work very well as a zoom, e.g. fish-eye lenses.

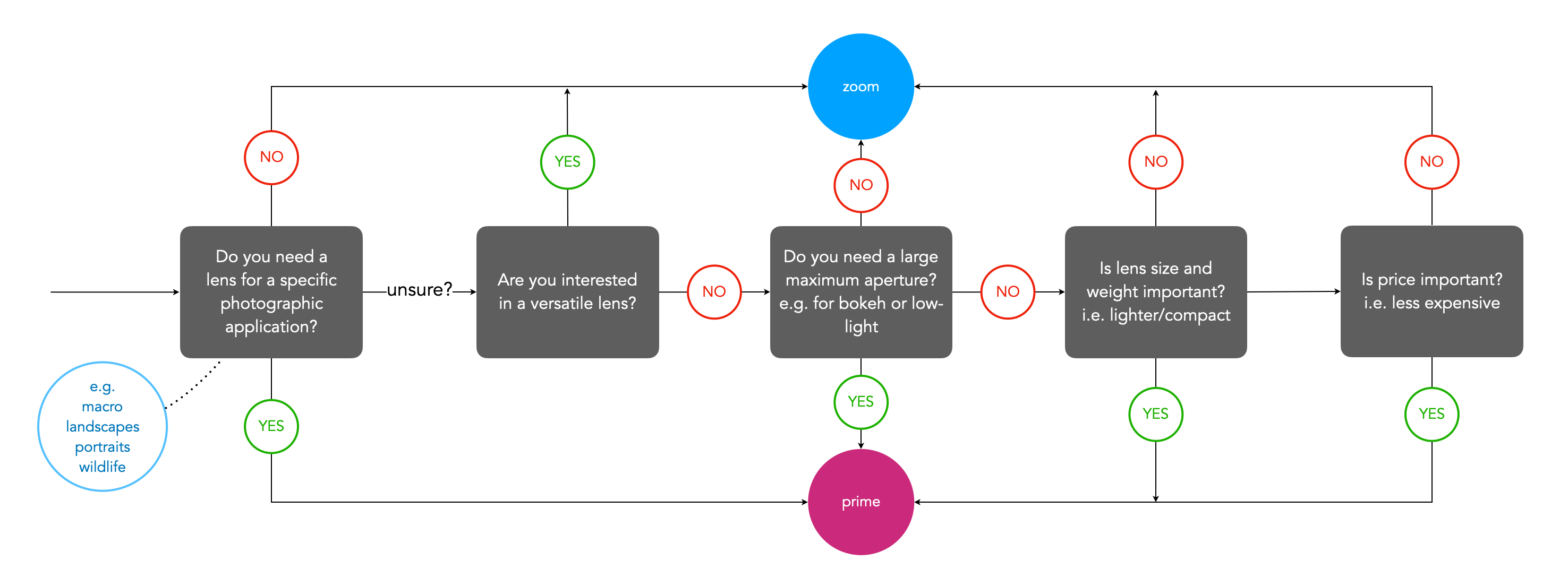

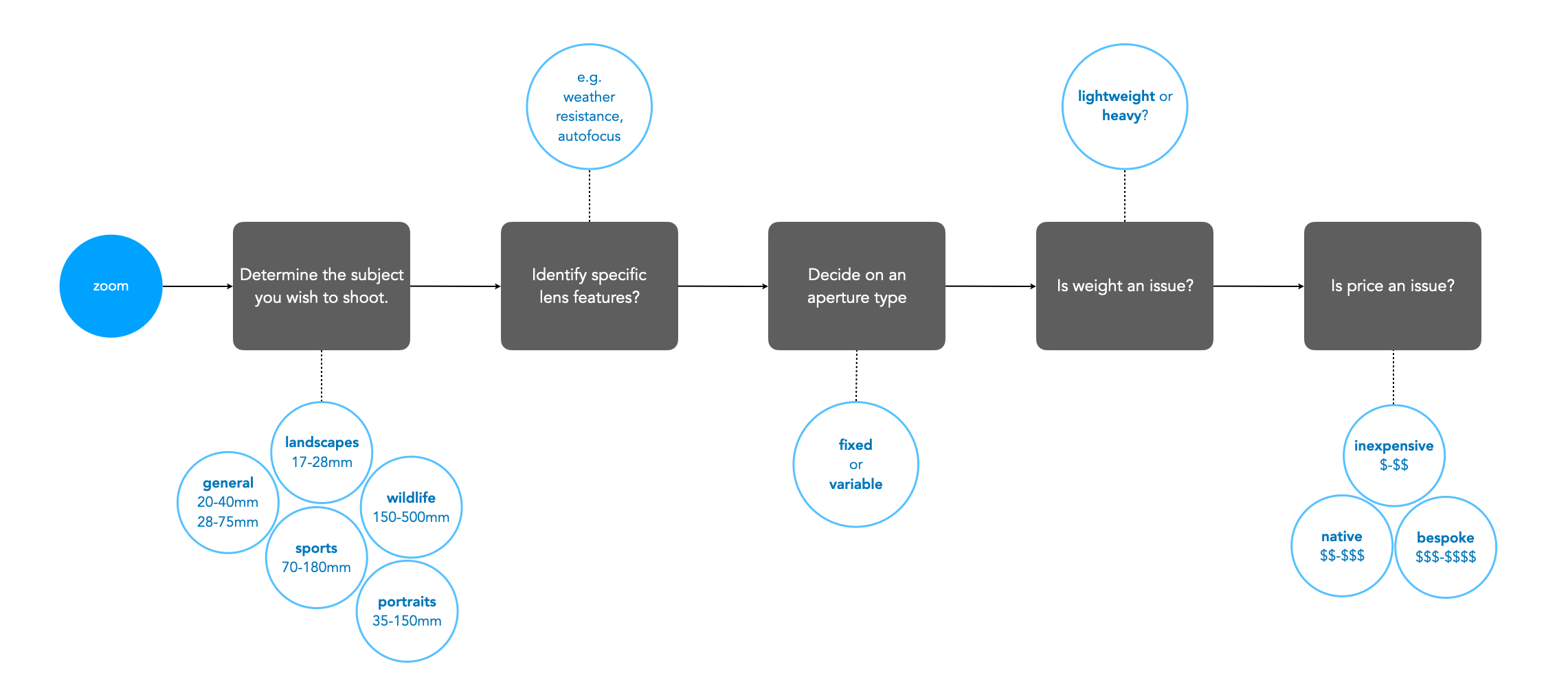

When selecting a prime lens it is often the case of deciding on an application, and then which lens meets all the criteria. For example, a trip to Iceland may warrant a wide-angle lens that is weatherproof (because the weather can change every 5 minutes in Iceland) − in this case something like a 24mm ultra-wide would be optimal. Alternatively, some photographers might opt for even a wider lens, e.g. 16/18mm due to the ‘largeness’ of the landscape. Choosing a zoom lens on the other hand can be a little more challenging. This is because there are often a variety of options. For example, choosing a 50mm prime means you get a 50mm lens, with perhaps the only variability being the speed (maximum aperture) of the lens. But there may be more than one option for choosing a particular zoom lens. Figure 2 shows a flowchart which considers some of the main factors to consider when choosing a zoom lens.

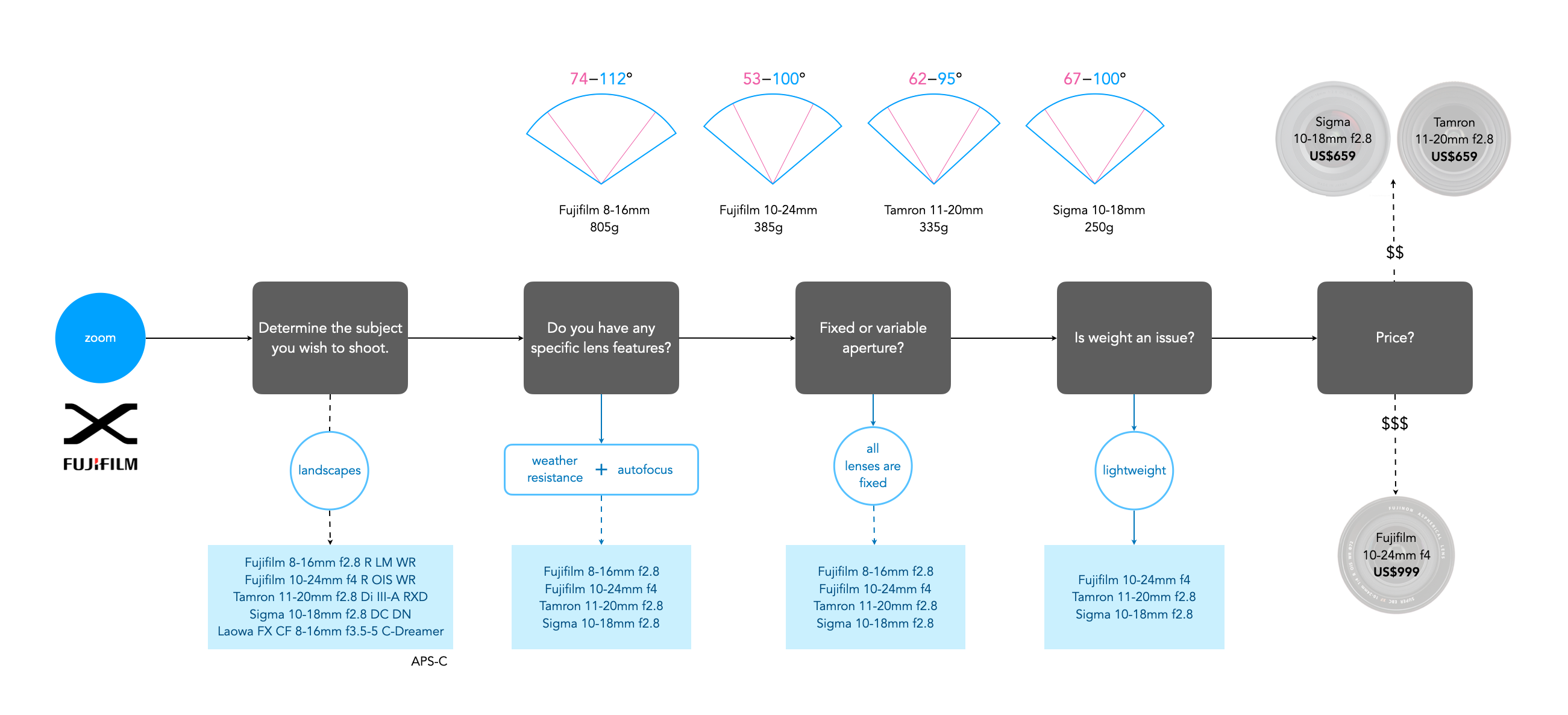

Figure 3 shows an example of choosing a wide zoom lens for a Fuji-X camera (APS-C), using the above factors. There isn’t that much difference between the lenses with respect to AOV (angle-of-view), but as each factor is considered, more lenses are filtered out. At the end only three of the five lenses satisfy the criteria considered, and then it comes down to price. If we were choosing this for the trip to Iceland then we might want the greatest flexibility in focal lengths, for example the Fujifilm 10-24mm (FF equivalent 15-36mm). If maximum aperture is an issue, then either the Tamron or Sigma are fine alternatives.

There are some situations where one lens is just enough. Mountain enthusiast Jakub Cejpek talks about using the Fujifilm XF10-24mm/F4 on a mountain trek. He chose mirrorless for its ‘lightweight style’, and the 10-24mm lens for its versatility, knowing that changing lenses in impossible, ‘time is rare, and weather conditions are tough’.