For many decades, achromatic black-and-white (B&W) photographs were accepted as the standard photographic representation of reality. That is until the realization of colour photography for the masses. Kodak introduced Kodachrome in 1936 and Ektachrome in the 1940s which lead to the gradual, popular adoption of colour photography. It only became practical for everyday photographers during the mid-1950s after film manufacturers had invented processes that made colour pictures sufficiently easy to develop. That didn’t mean that B&W disappeared from society, as in certain fields like journalistic photography they remained the norm. There were a number of reasons for this – news photos were generally printed in B&W, and B&W film was faster, meaning less light was needed to take an image, allowing photojournalists to shoot in a variety of conditions. So from a journalistic viewpoint, people interpreted the news of the world in B&W for nearly a century.

The difference between B&W and colour is that humans don’t see the world in monochromatic terms. Humans have the potential to discern millions of colours, and yet are limited to approximately 32 shades of gray. We have evolved in this manner because the world around us is not monochromatic, and our very survival once depended on our ability to separate good food from the not so good. Many things can be inferred from colour. Many things are lost in B&W. Colour catches the eye, and highlights regions of interest. For instance, setting and time of day/year can be inferred from a photograph’s colours. Mood can also be communicated based on colour.

Black-and-white photographs offer a translation of our view of the world into a unique achromatic medium. Shooting B&W photographs is clearly more challenging because unlike the 16 million odd colours available to describe a scene, B&W typically offers only 256, from pure black (0), to pure white (255). Take for example a photograph taken during the First World War. These photographs were typically B&W, and grainy, painting a rather grim picture of all aspects of society during this period. We typically associated B&W with nostalgia. There was some colour photography during the early 20th century, provided by the Autochrome Lumière technology, and resulting in some 72,000 photographs of the time period from places all over the world. But seeing things in B&W means having to interpret a scene without the advantage of colour. Consider the following photograph from Paris during the early 1900s. It offers a very vibrant rendition of the street scene, with the eye drawn to the varied colour posters on the wall of the building.

Without the colour, we are left with a somewhat drab and gloomy scene, befitting the somber mood associated with the early years of the early 20th century. In the B&W we cannot see the colour of the posters festooning the buildings. What is interesting is that we are likely not use to seeing colour photographs from before the 1950s. It’s almost like we expect images from the before 1950 to be monochromatic, maybe because we perceive these years filled with hardship and suffering. But there is something unique about the monochrome domain.

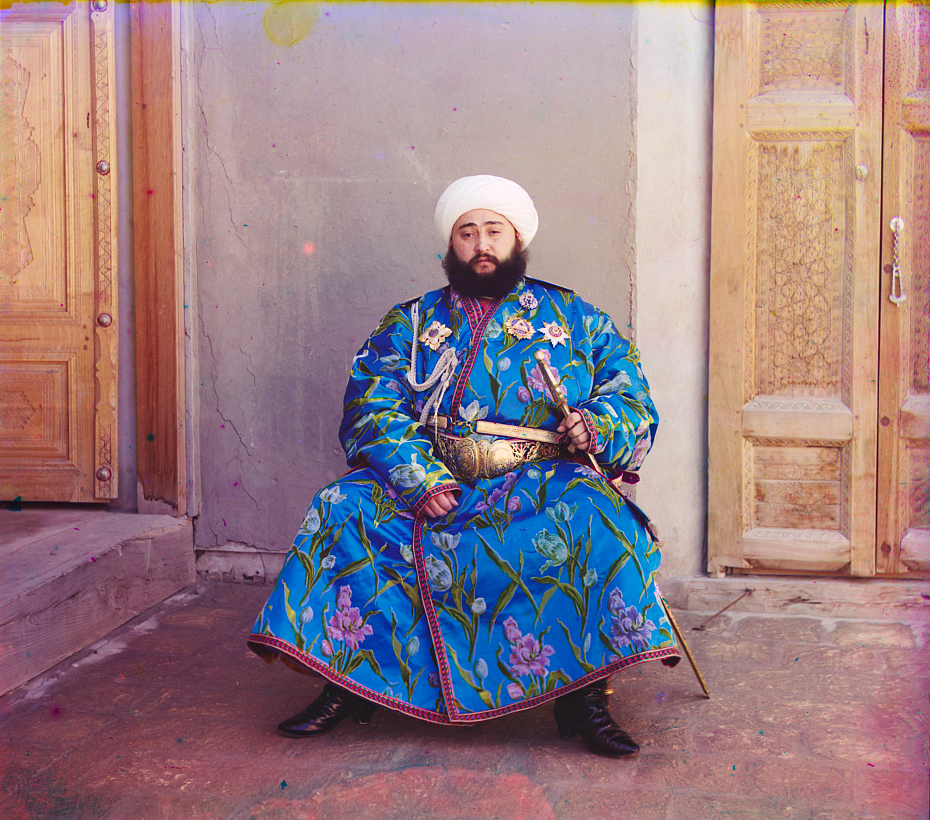

The aesthetic of black-and-white photographs is based on many factors, including lighting, any colour filters that were used during acquisition of the photograph, and the colour sensitivity of the B&W film. Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii (1863-1944) was a man well ahead of his time. He developed an early technique for taking colour photographs involving a series of monochrome photographs and colour (R-G-B) filters. The images below show an example of Alim Khan, Emir of Bukhara. It is shown in comparison with two grayscale renditions of the photograph. The first is the lightness component from the Lab colour space, and the second is a grayscale image extracted from RGB using G=0.299R+0.587G+0.114B. Both offer a different perspective of how the colour in the image could be rendered by the camera. None present the vibrance of the image in the same way as the colour image.