A camera either tells a lie, or does not tell a lie. It may seem somewhat confusing, but it is all a matter of perspective.

The camera, being a machine, cannot really lie because the picture it is taking is what it is designed to take. Therefore every unmanipulated photograph, no matter its context is essentially true. This includes the use of things like film simulations – if the settings in a Fujifilm camera are modified to take a photograph using a simulation to mimic Kodak Porta 400 film, then the picture produced is true. On the other hand, the human eye, being subject to the interpretation of the brain often sees things differently from the camera lens with the result being that what the camera perceives as true, appears as false. In other words, it is the human eye that lies, or deceives us. Therefore to make the cameras rendition correspond closer to the humans perception, a photographer may have to force a camera to effectively tell a lie. The resulting picture then is a constructive lie, because the lie serves a constructive purpose.

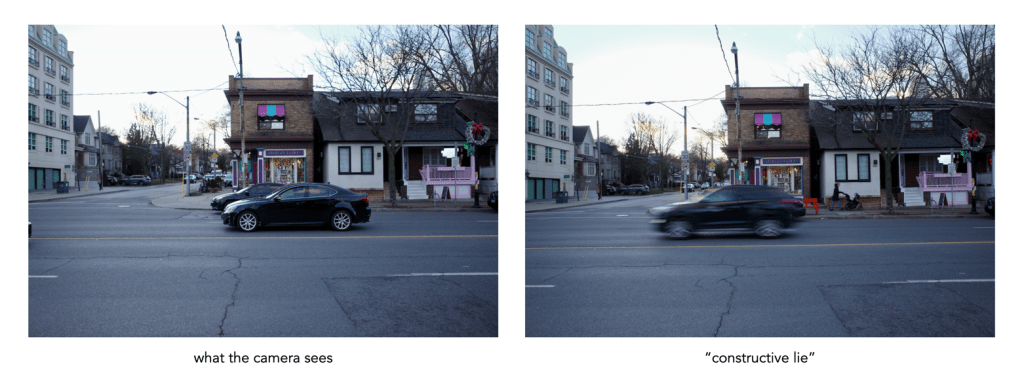

Consider as an example, cars driving down a road. Since your eyes can follow the cars in transit, you can perceive them in the form of sharp images, while understanding that the cars are actually moving. A camera, using the appropriate fast shutter speed, will freeze the scene, effectively giving the erroneous impression that the cars on the road are standing still. There is no real difference between a picture of the cars in motion, or standing still. Motion can be rendered in the photograph with blur – using a slow shutter speed will cause a slight blur in the rendering of the picture. The eye does not see this blur in real life, so the photograph would not be true, but rather a constructive lie. The resulting image is much more descriptive of the scene.

Another example of a constructive lie deals with the colour temperature of a scene. The lighting in a scene may not create the most optimal scene from a visual perspective, perhaps due to the temperature of the light source, resulting in what is known as a colour cast. As a result a photographer may modify the temperature by means of a white balancing setting to the point where the eye perceives it as “normal”. For example a scene lit by a tungsten light would have an orange hue. A photograph taken of this scene would have a corresponding colour cast, which would be rejected by the brain as seeming “unnatural”, because colour memory makes us see things in the same light as a sunlit scene. This is another case where the photograph of the scene is “true”, and the corrected version is false – constructive lie.

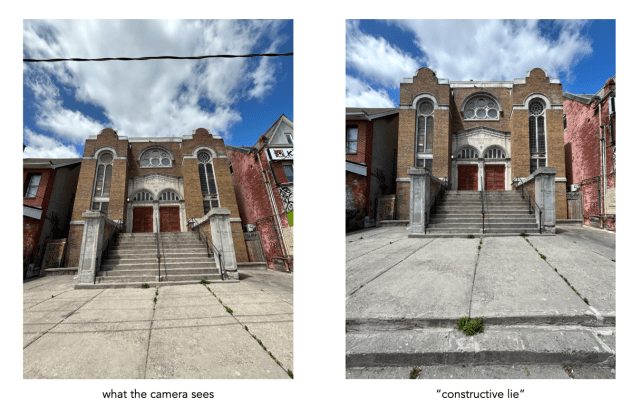

The third example is the classic one where tall building appear somewhat skewed, leaning back into the scene – what is known as the keystone effect. This convergence of parallel lines is a perfectly natural example of perspective, which is perfectly acceptable in the horizontal plane, e.g. railway tracks, but seemingly deplorable in the vertical plane. Converging lines are easy to fix, either by means of the tilt-shift lens, or using software (some cameras have this built-in), with the resulting image being a constructive lie as opposed to the seeing the building as it really appears.