The first permanent photograph was produced in 1825 by the French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. Since then photographs have become the epitome of our visual history. Until becoming widespread in the 1950s, colour images were more of an aberration, with monochrome, i.e. black-and-white, being the norm, partially due to the more simplistic processing requirements. As a result, history of good portion of the 19th/20th centuries is perceived in terms of monochromic images. This determines how we perceive history, for humans perceive monochromatic images in a vastly differing manner to colour ones.

The use of black-and-white in historical photographs implies certain ideas about history. There is the perception that such photos are authentic historical images. By the mid half of the 19th century, photography had become an important means of creating a visual record of life. However the process was inherently monochromatic, and the resulting photographs provided a representation of the structure of a subject, but lacked the colour which would have provided a more realistic context. There were some photographic processes which yielded an overall colour, such as cyanotypes, however such colour was unrealistic. The first colourization of photographic occurred in the early 1840s, when Swiss painter Johann Baptist Isenring used a mixture of gum arabic and pigments to make the first coloured daguerreotype. Such hand colouring continued in successive mediums including albumen and gelatin silver prints. The purpose of this hand-colouring may have been to increase the realism of the photographic prints (in lieu of a colour photographic process) .

The major failing of monochromatic images may be the fact that they suffer from a lack of context. Removing the colour from an image provides us with a different perception of the scene. Take for example the picture of the Russian peasant girls shown in Fig. 1. The image is from the US Library of Congress Prokudin Gorskii Collection, and depicts three young women offering berries to visitors to their izba, a traditional wooden house, in a rural area along the Sheksna River, near the town of Kirillov. Shown in colour, we perceive a richness in the girls garments, even though they are peasant girls in some small Russian town. When we think of peasant Russia in the early 20th century, we are unlikely to associate such vibrant colours with their place in society. Had we viewed only the panchromatic image, our perception would be vastly different.

Humans are capable of perceiving approximately 32 shades of gray and millions of colours. When we interpret an image to extract descriptors, some of those descriptors will be influenced by the perceived colour of objects within the image. A monochrome image relies on a spectrum of intensities that range from black to white, so when we view a monochromatic image, we perceive the image based on tone, texture and contrast, rather than colour. In the photograph of the peasant girls we are awed by the dazzling red and purple dresses, when viewing the monochrome image we are drawn to the shape of the dresses, the girls pose, and the content of the image.

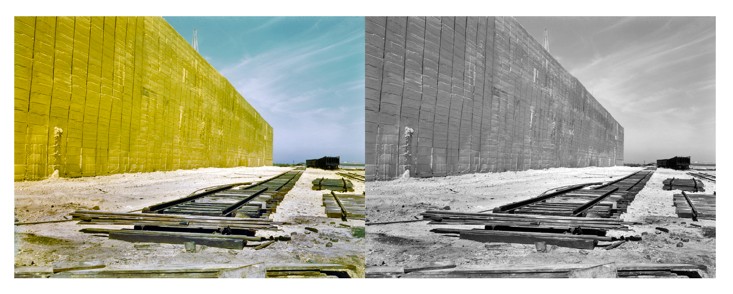

Here is a second example of a sulfur stack shown in both colour and grayscale. The loss of meaning in the monochrome image is clear. The representative stack of sulphur is readily identifiable in the colour image, however in the monochrome image, the identifying attribute has been removed, leaving only the structure of the image with a loss of context.