Hang a large, scenic panorama from a wall, and the picture of the scene looks like the scene itself. Photographs are mere imitations of life, albeit flat renditions. Yet although they represent different realities, there are cues on the flat surface of a photograph which help us perceive the scene in depth. We perceive depth is photographs (or even paintings) because the same type of information reaches our visual system from photographs of scenes as from the scenes themselves.

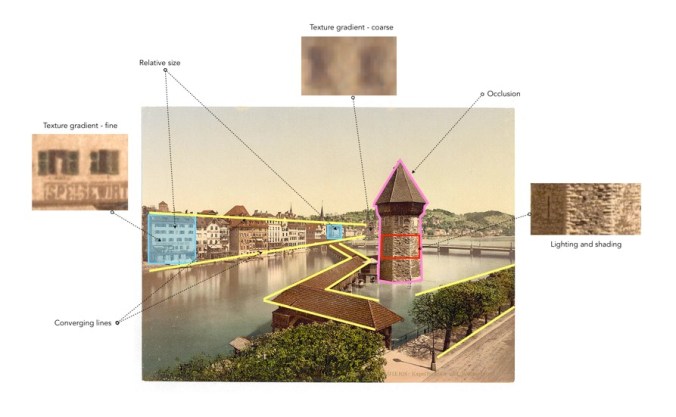

Consider the following Photochrom print (from the Library of Congress) of the Kapellbrücke in the Swiss city of Lucerne, circa 1890-1900. There is no difficulty perceiving the scene as it relates to depth. It is possible to identify buildings and objects in the scene, and obtain an understanding of the relative distances of objects in the scene from one another. These things help define its “3D” ness. The picture can be seen from another perspective as well. The buildings on the far side of the river get progressively smaller as they progress along the river from the left to right, and the roof of the bridge is much larger in the foreground than it is in the distance. There is no motion parallax, which is the relative movement of near and far objects were we physically moving around the scene. These things work together to define our perception of the prints flatness.

Our perception of the 3D nature of a flat photograph comes from the similarity of information reaching the human visual system from an actual 3D scene, and one described in a photograph of the same scene.

What depth cues exist in an image?

- Occlusion – i.e. overlapping or superimposition. If object A overlaps object B, then it is presumed object A is closer than object B. The water tower in Fig.1 hides the buildings on the hill behind it, hence it is closer.

- Converging lines – As parallel lines go into the distant, they become closer together. The bridge’s roofline in Fig.1 gets smaller as it moves higher in the picture.

- Relative size – Objects that are larger in an image are perceived to be closer than those which are further away. For example, the houses along the far riverbank in Fig. 1 are roughly the same height, but become smaller as they progress from the left of the picture towards the centre.

- Lighting and shading – Lighting is what brings out the form of a subject/object. The picture in Fig. 1 is light on the right, and darker on the right, this is effectively shown in the water tower which has a light side, and a side with shadows. This provides information about the shape of the tower.

- Contrast – For scenes where there is a large distance between objects, those further away will have a lower contrast, and may appear blurrier.

- Texture gradient – The amount of detail on an object helps understand depth. Objects that are closer appear to have more detail, and as it begins to loose detail those areas are perceived to be further away.

- Height in the plane – An object closer to the horizon is perceived as being more distant than objects above or below it.

Examples of some of these depth cues are explained visually below.