When it comes to megapixels, the bottom line might be how an image ends up being used. If viewed on a digital device, be it an ultra-resolution monitor or TV, there are limits to what you can see. To view an image on an 8K TV at full resolution, we would need a 33MP image. However any device smaller than this will happily work with a 24MP image, and still not display all the pixels. Printing is however another matter all together.

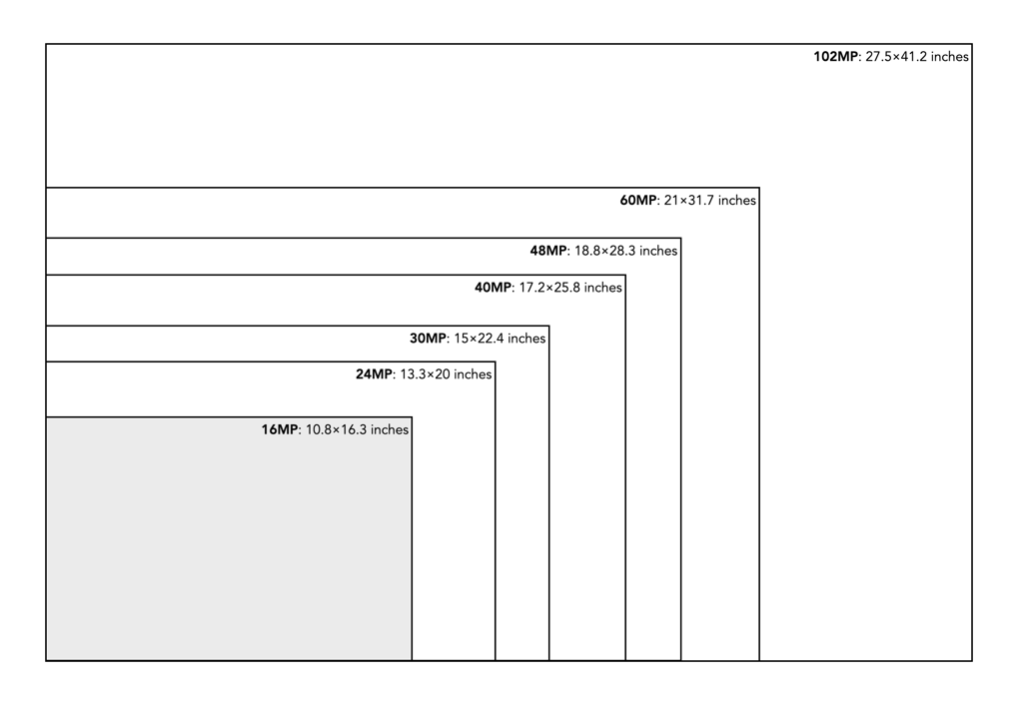

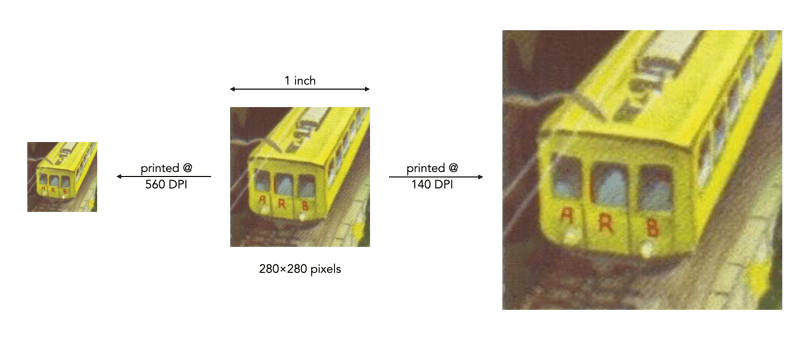

The standard for quality in printing is 300dpi, or 300 dots-per-inch. If we equate a pixel to a dot, then we can work out the maximum size an image can be printed. 300 dpi is generally the “standard”, because that is the resolution most commonly used. To put this into perspective, at 300dpi, or 300 dots per 25.4mm, each pixel printed on a medium would be 0.085mm, or about as thick as 105 GSM weight paper. That means a dot area of roughly 0.007mm². For example a 24MP image containing 6000×4000 pixels can be printed to a maximum size of 13.3×20 inches (33.8×50.8cm) at 300dpi. The print sizes for a number of different sized images printed using 300dpi are shown in Figure 1.

The thing is that you may not even need 300dpi? At 300dpi the minimum viewing distance is theoretically 11.46”, whereas dropping it down to 180dpi means the viewing distance increases to 19.1” (but the printed size of an image can increase). In the previous post we discussed visual acuity in terms of the math behind it. Knowing that a print will be viewed from a minimum of 30” away allows us to determine that the optimal DPI required is 115. Now if we have a large panoramic print, say 80″ wide, printed at 300dpi, then the calculated minimum viewing distance is ca. 12″ – but it is impossible to view the entire print being only one foot away from it. So how do we calculate the optimal viewing distance, and then use this to calculate the actual number of DPI required?

The amount of megapixels required of a print can be guided in part by the viewing distance, i.e. the distance from the centre of the print to the eyes of the viewer. The golden standard for calculating the optimal viewing distance involves the following process:

- Calculate the diagonal of the print size required.

- Multiply the diagonal by 1.5 to calculate the minimum viewing distance

- Multiply the diagonal by 2.0 to calculate the maximum viewing distance.

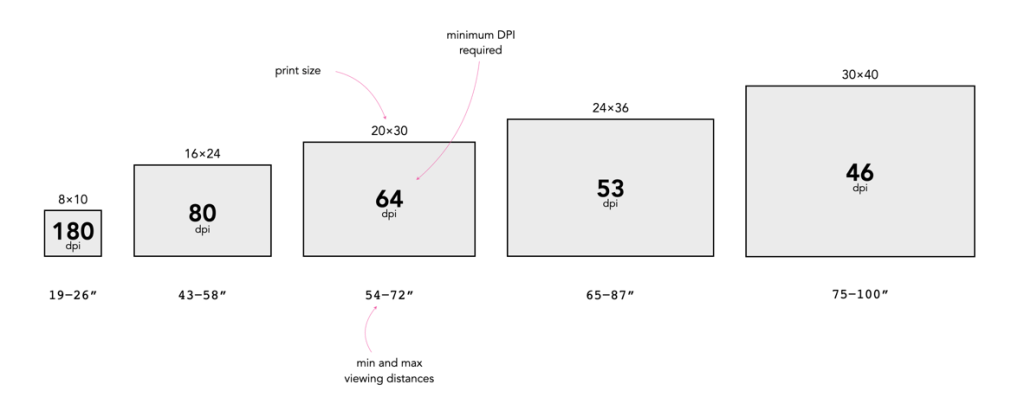

For example a print which is 20×30″ will have a diagonal of 36″, so the optimal viewing distance range from minimum to maximum is 54-72 inches (137-182cm). This means that we are no longer reliant on the use of 300dpi for printing. Now we can use the equations set out in the previous post to calculate the minimum DPI for a viewing distance. For the example above, the minimum DPI required is only 3438/54=64dpi. This would imply that the image size required to create the print is (20*64)×(30*64) = 2.5MP. Figure 2 shows a series of sample print sizes, viewing distances, and minimum DPI (calculated using dpi=3438/min_dist).

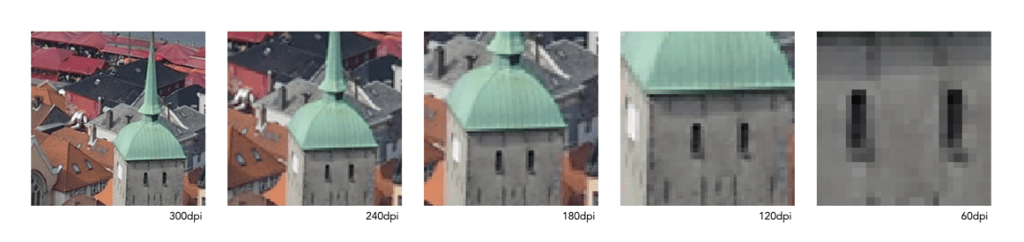

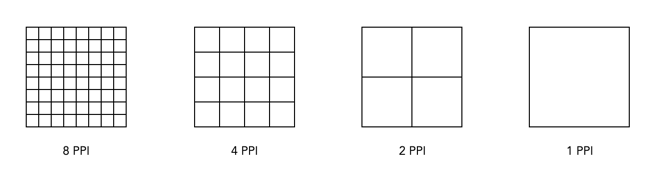

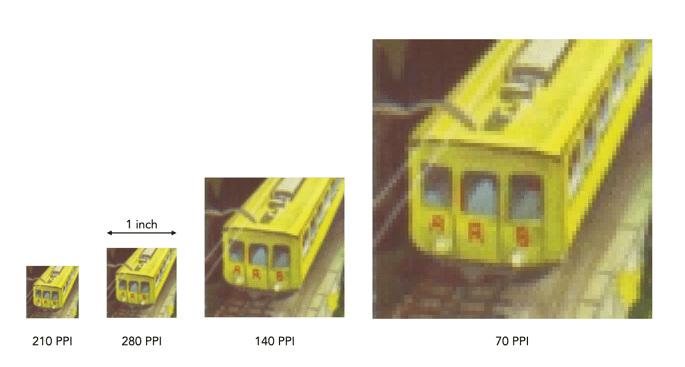

Now printing at such a low resolution likely has more limitations than benefits, for example there is no guarantee that people will view the panorama from a set distance. So there likely is a lower bound to the practical amount of DPI required, probably around 180-200dpi because nobody wants to see pixels. For the 20×30″ print, boosting the DPI to 200 would only require a modest 24MP image, whereas a full 300dpi print would require a staggering 54MP image! Figure 3 simulates a 1×1″ square representing various DPI configurations as they might be seen on a print. Note that even at 120dpi the pixels are visible – the lower the DPI, the greater the chance of “blocky” features when view up close.

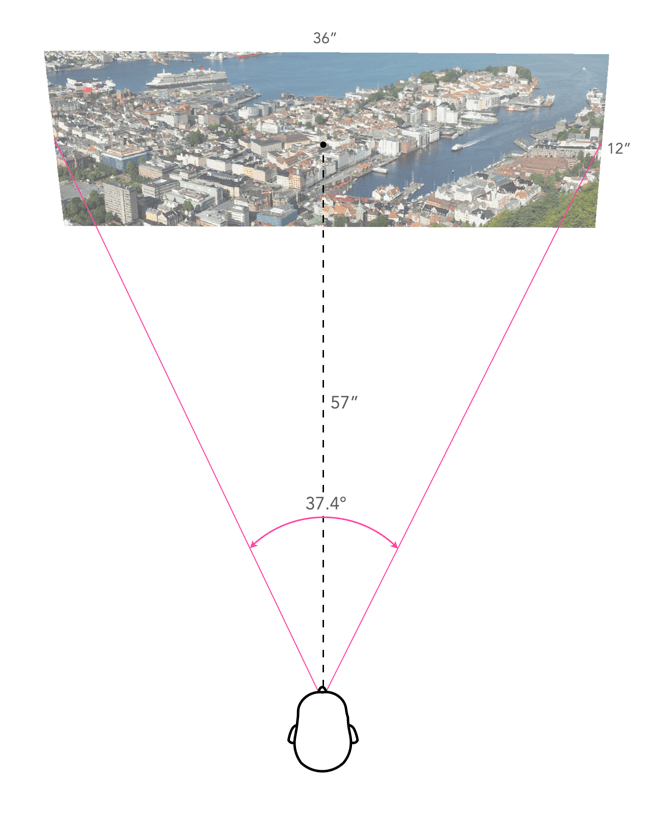

Are the viewing distances realistic? As an example consider the viewing of a 36×12″ panorama. The diagonal for this print would be 37.9″, so the minimum distance would be calculated as 57 inches. This example is illustrated in Figure 4. Now if we work out the actual viewing angle this creates, it is 37.4°, which is pretty close to 40°. Why is this important? Well THX recommends that the “best seat-to-screen distance” (for a digital theatre) is one where the view angle approximates 40 degrees, and it’s probably not much different for pictures hanging on a wall. The minimum resolution for the panoramic print viewed at this distance would be about 60dpi, but it can be printed at 240dpi with an input image size of about 25MP.

So choosing a printing resolution (DPI) is really a balance between: (i) the number of megapixels an image has, (ii) the size of the print required, and (iii) the distance a print will be viewed from. For example, a 24MP image printed at 300dpi will allow a maximum print size of 13.3×20 inches, which has an optimal viewing distance of 3 feet, however by reducing the DPI to 200, we get an increased print size of 20×30 inches, with an optimal viewing distance of 4.5 feet. It is an interplay of many differing factors, including where the print is to be viewed.

P.S. For small prints, such as 5×7 and 4×6, 300dpi is still the best.

P.P.S. For those who who can’t remember how to calculate the diagonal, it’s using the Pythagorean Theorem. So for a 20×30″ print, this would mean:

diagonal = √(20²+30²)

= √1300

= 36.06