Lens descriptors, those one-liners that describe the characteristics of a lens use to be simpler. Consider the older Leica lens box shown below. A brand, a lens name, aperture, focal length, and a lens profile. But then maybe lenses were simpler? I guess they could have festooned the descriptor with lens coatings, and other fancy acronyms describing interesting lens features, but they didn’t, probably because whoever was in charge of marketing realized that lens descriptors need to be simple.

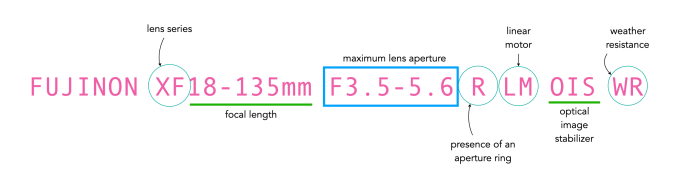

Many companies now give their lenses such complex descriptors it’s easy for people to get confused. Often the difference between two generations of a lens is the addition of another acronym on the newer lens. Take Fujifilm lenses as an example. I love Fujifilm lenses, but their names are a bit of a mouthful… to the extent that Fujifilm actually includes a section in their brochures called ‘Lens Names Explained‘. Here is an example of a Fujifilm lens descriptor:

There is a lot of information in this label, mostly describing the characteristics of the lens, such as weather-resistance, the type of motor driving the focusing mechanism, and whether the lens has a physical aperture ring or not. Most companies that produce lenses seem to have some sort of guide to explain their terminology. Canon provides ‘How to read a lens name‘ where they talk about lens mount, focal length and aperture (the easiest things to explain), and then a myriad of abbreviations to explain technology: L (Luxury), DO (diffractive optics), DS (defocus smoothing coating), IS (image stabilization), and focusing motor (USM/Nano USM/STM/Macro). or perhaps Sony’s ‘Lens terminology‘?

For the average user, it’s just too much information. Can things be improved? Yes − by simplifying naming conventions, i.e. removing the acronyms and abbreviations. Put them somewhere else, because most people in the first instance are interested in ① focal length, ② maximum aperture, and perhaps ③ weather resistance (and let’s be honest, price). I’m not even sure it matters if the acknowledgement of aspherical lens elements is necessary, or even the type of focusing motor. The only people that likely care are professional photographers. I mean most lenses have pages contains their specs that people will read, so is there any point to including so much detail in a lens descriptor? Perhaps try and create some industry standard symbols. For example using a symbol to denote weather resistance, e.g. ☔︎.

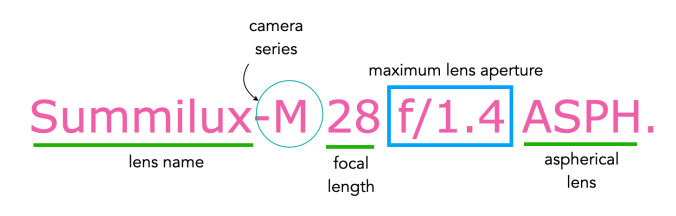

Below is a much simpler description of a Leica lens. Mostly just the basics, although I don’t really know why they include the fact the lens contains aspherical elements (ASPH)?

Although I always thought that in the age of different sensor sizes, it might be better to forgo the focal length, and replace it with the lenses angle-of-view (the horizontal one that is, not the nonsensical diagonal one). So for the example lens above (for full frame) this would be 65°. This would also avoid the whole issue with designating lenses, e.g. crop-sensor. Maybe the issue is also that lenses really don’t have ‘names’ anymore, well except for maybe Leica and Zeiss.

I understand, digital lenses are way more complex than their historical counterparts, and companies are continuously adding new features. But where does it end? Do we add lens elements/group data to the descriptor? What about lens coatings? The presence of ASPH already shows some creep of internal technology onto the side of a lens box. How important is it to know that a lens has aspherical elements? Do we also need to signify the existence pf extra-low dispersion glass?

I get it, it’s all about selling the lens, but the more complicated a lens descriptor is, the more questions that have to be asked.