If you know someone who dabbles in photography, and are looking for a Christmas gift, below are some book ideas. Some are new, others can be found on the vintage market, e.g. Abebooks.

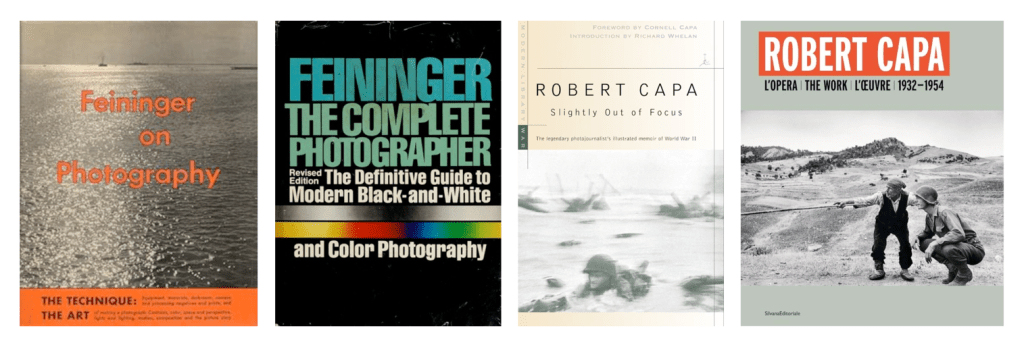

- Any book by photographer Andreas Feininger. He produced a lot of really good books on photographic knowledge. Good ones include Feininger on Photography (1949), and The Complete Photographer (1965). Theses books are less about technology, and more about technique, much of which is just as relevant today in the age of digital.

- Robert Capa’s book, Slightly Out Of Focus: The Legendary Photojournalist’s Illustrated Memoir Of World War II (reprint 2001). A good insight into Hungarian photographer Robert Capa’s experiences during WW2 from the man himself.

- A deeper dive Capa’s photographs can be found in the more recently published Robert Capa: The Work 1932-1954 (2023).

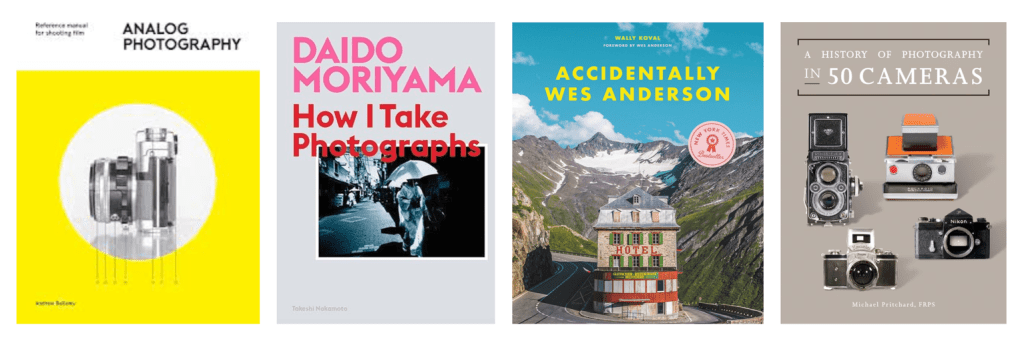

- A very minimalistic approach to film photography can be found in Analog Photography: Reference Manual for Shooting, by Andrew Bellamy (2017). It dives into the fundamentals of 35mm film photography.

- In Daido Moriyama: How I Take Photographs (2019), Japanese street photographer Daido Moriyama explains his approach to street photography. A great book for anyone interested in getting a real insight into street photographer from one of the icons of the genre.

- A great coffee table book is Accidentally Wes Anderson (2020), photographs of real places plucked from the world of his films.

- For a vintage camera buff, there is a great little book, A History Of Photography In 50 Cameras (2022), which explores 180 years of photography through 50 iconic cameras.