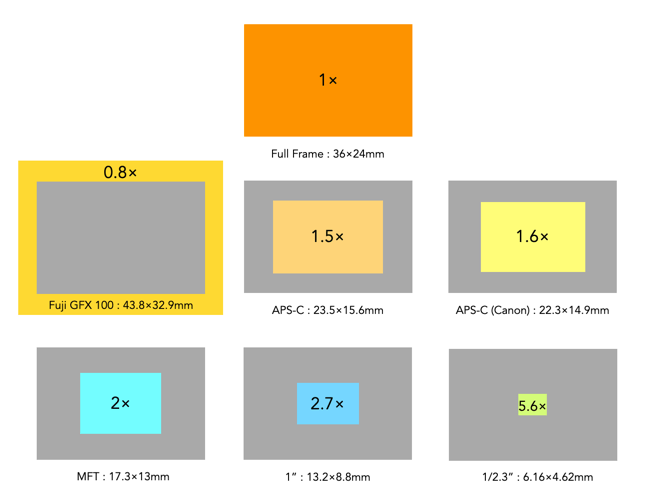

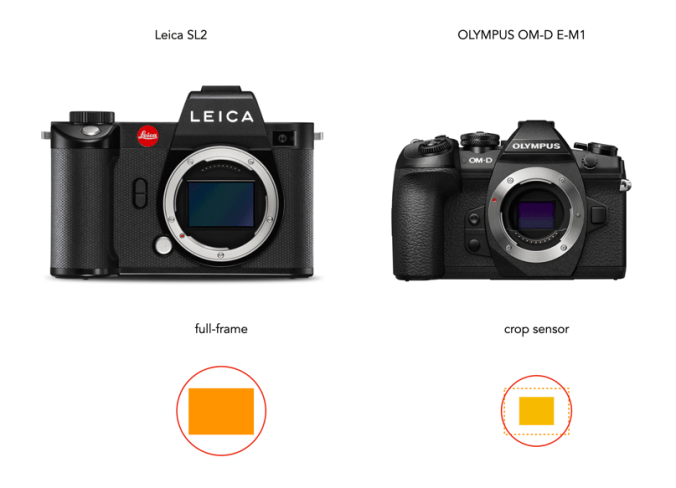

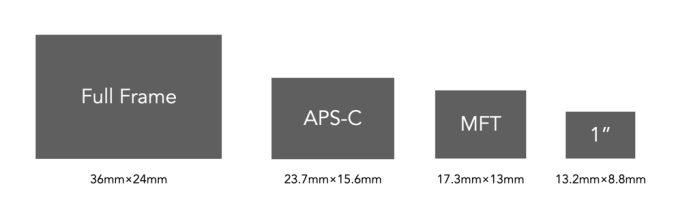

The term “crop-sensor” doesn’t make much sense anymore, if it ever did. I understand why it evolved, because a term was needed to collectively describe smaller-than-35mm sized sensors (crop means to clip or prune, i.e. make smaller). That is, if it’s not 36×24mm in size it’s a crop-sensor. However it’s also sometimes used to describe medium-format sensors, even though they are larger than 36×24mm. In reality non-35mm sensors do provide an image which is “cropped” in terms of comparison with a full-frame sensor, but taken in isolation they are sensors unto themselves.

The problem lies with the notion that 36×24mm constitutes a “full-frame”, which only exists as such because manufacturers decided to continue using the concept from 35mm film SLR’s. It is true that 35mm was the core film standard for decades, but that was constrained largely by the power of 35mm film. Even half-frame cameras (18×24mm, basically APS-C size) used the same 35mm film. In the digital realm there are no constraints on a physical medium, yet we are still wholly focused on 36×24mm.

Remember, there were sub-full-frame sensors before the first true 36×24mm sensor appeared. Full-frame evolved in part because it made it easier to transition film-based lenses to digital. In all likelihood in the early days there were advantages to full-frame over its smaller brethren, however two decades later we live in a different world. “Crop” sensors should no longer be treated as sub-par players in the camera world. Yet it is this full-frame mantra that sees people ignore the benefits of smaller sensors. Yes, there are benefits to full-frame sensors, but there are also inherent drawbacks. It is the same with the concept of equivalency. We say a 33mm APS-C lens is “equivalent” to a 50mm full-frame. But why? Because some people started the trend of relating everything back to what is essentially a 35mm film format. But does there even need to be a connection between different sensors?

The reason “crop” sensors have continued to evolve is because they are much cheaper to produce, and being smaller, the cameras themselves have a reduced footprint. Lenses also require less glass, making them lighter, and less expensive to manufacture. Maybe instead of using “crop-sensor”, we should just acknowledge the sensors exactly as they are: Medium, APS-C, and MFT, and change full-frame to be “35mm” format instead. So when someone talks about a 35mm sensor, they are effectively talking about a full-frame. All it takes is a little education.

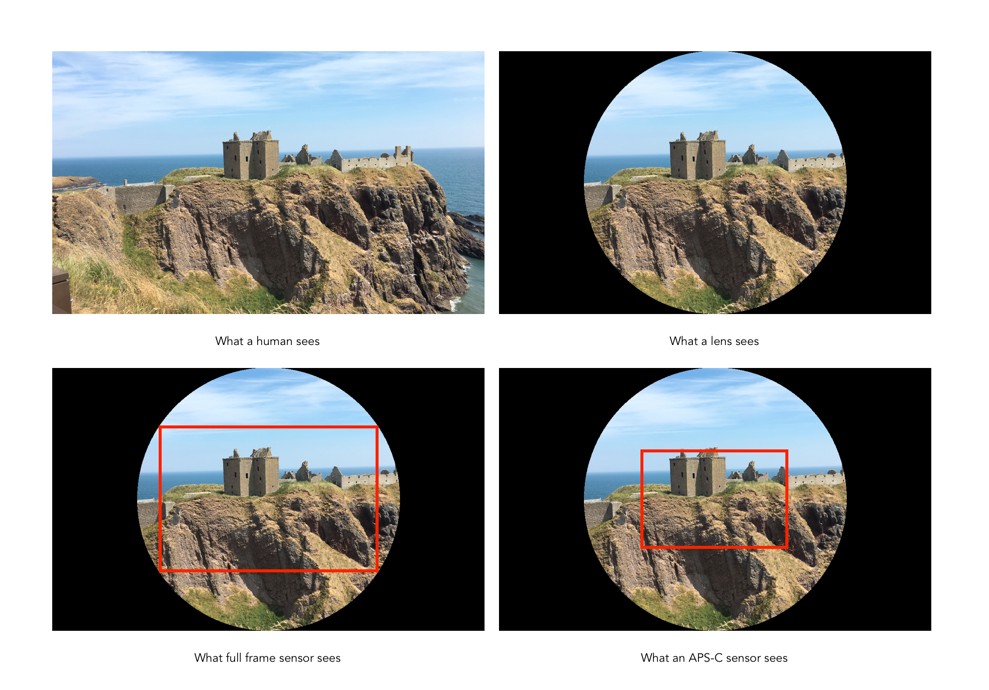

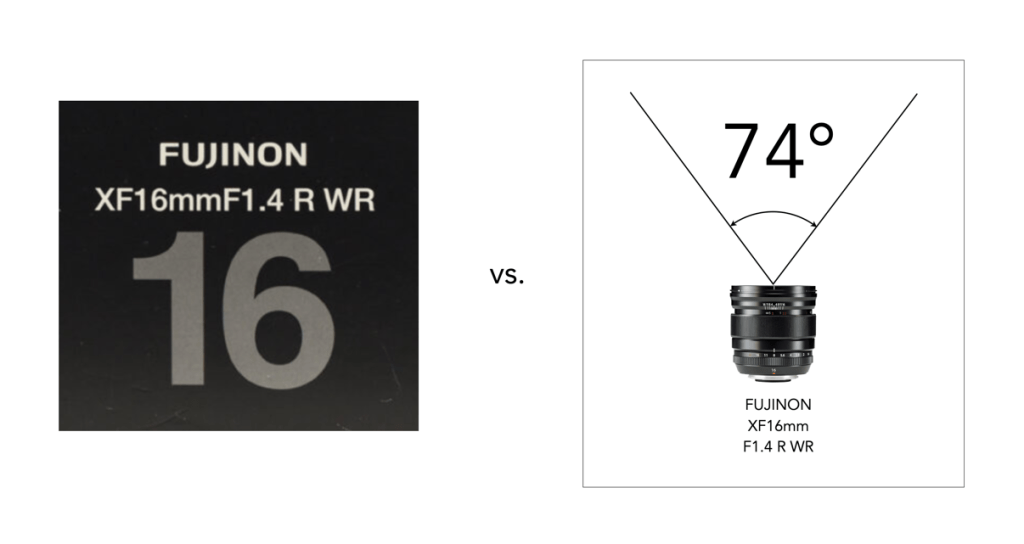

Using the term-crop sensor also does more harm than good, because it results in more terms: equivalency and crop-factor which are used in the context of focal length, AOV, and even ISO. People get easily confused and then think that a lens with a focal length of 50mm on an APS-C camera is not the same as one on a FF camera. Focal lengths don’t change, a lens that is 50mm is always 50mm. What changes is the Angle-of-View (AOV). A larger sensor gives a wider AOV, whereas a smaller sensor gives a narrower AOV. So while the 50mm lens on the FF camera has a horizontal AOV of 39.6°, the one on the APS-C camera sees only 27°.

It would be easier not to have to talk about a sensor in terms of another sensor. But even though terms like “crop-sensor” and “crop-factor” are nonsensical, in all likelihood the industry won’t change the way they perceive non-35mm sensors anytime soon. I have previously described how we could alleviate the term crop-factor as it relates to lenses, identifying lenses based on their AOV rather than purely by their focal length. This works because nearly all lenses are designed for a particular sensor, i.e. you’re not going to buy a MFT lens for an APS-C camera.