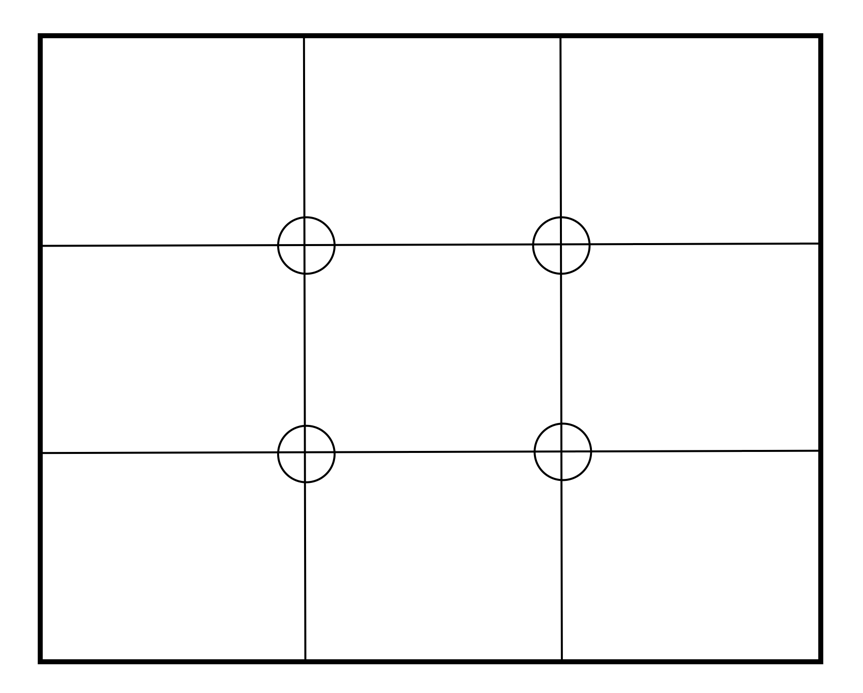

The “Rule of Thirds” (ROT) is a concept used for the composition of a photograph. It states that the centre of interest in a photograph should be placed at any one of the four intersections of four imaginary lines, two of which bisect the frame horizontally, and two of which bisect it vertically, dividing the picture into thirds each way. It’s main goal is to move the subject out of the centre of the image, because having the subject to one side produces visual interest.

But this idea did not originate in photography, but rather art, i.e. painting. In 1783 Sir Joshua Reynolds taught at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, mentioning in his discourses how a painting works best when the use of light and dark has a ratio of approximately ⅓ : ⅔. It is described in a book entitled “Remarks on rural scenery : with twenty etchings of cottages, from nature : and some observations and precepts relative to the pictoresque“, by John Thomas Smith and Joseph Downes in 1797, where is it first defined.

Two distinct, equal lights, should never appear in the same picture : One should be principal, and the rest sub-ordinate, both in dimension and degree : Unequal parts and gradations lead the attention easily from part to part, while parts of equal appearance hold it awkardly suspended, as if unable to determine which of those parts is to be considered as the subordinate. “And ” to give the utmost force and solidity to your work, some part of ” the picture should be as light, and some as dark as possible: ” These two extremes are then to be harmonized and reconciled ” to each other.”

Analogous to this “Rule of thirds”, ( if I may be allowed so to call it ) I have presumed to think that, in connecting or in breaking the various lines of a picture, it would likewise be a good rule to do it, in general, by a similar scheme of proportion ; for example, in a design of landscape, to determine the sky at about two-thirds ; or else at about one-third, so that the material objects might occupy the other two : Again, two thirds of one element, ( as of water ) to one third of another element ( as of land ) ; and then both together to make but one third of the picture, of which the two other thirds should go for the sky and serial perspectives.

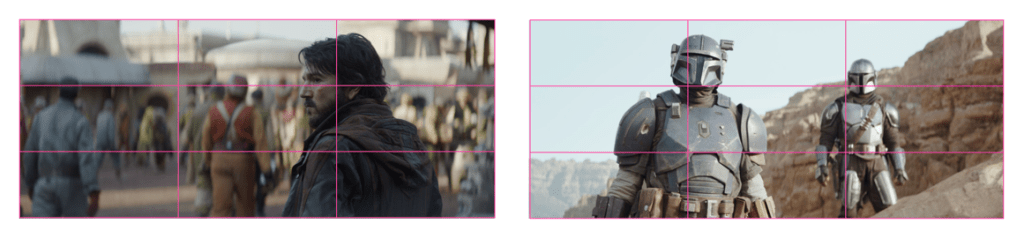

How it got to photography is somewhat mystical. Search for it in books of the mid-20th century, and you won’t find it. For example The Amateur Photographer’s Handbook, by Aaron Sussman, published for about four decades from 1941 on wards does not mention it. It is possible that it transitioned from the cinematic industry where it is commonly used [1]. Consider the examples shown in Figure 2. In the left image, the character clearly is framed in the right third of the frame, whilst in the right image the background and foreground characters are framed at opposite sides of the intersecting lines.

By the 1980s it was often mentioned in passing as a mean of composition, but the past two decades has seen it blossom online, both for use in still photography and video. You can commonly find it being used as the composition guides overlaid on screens on cameras as a means to help with composition.

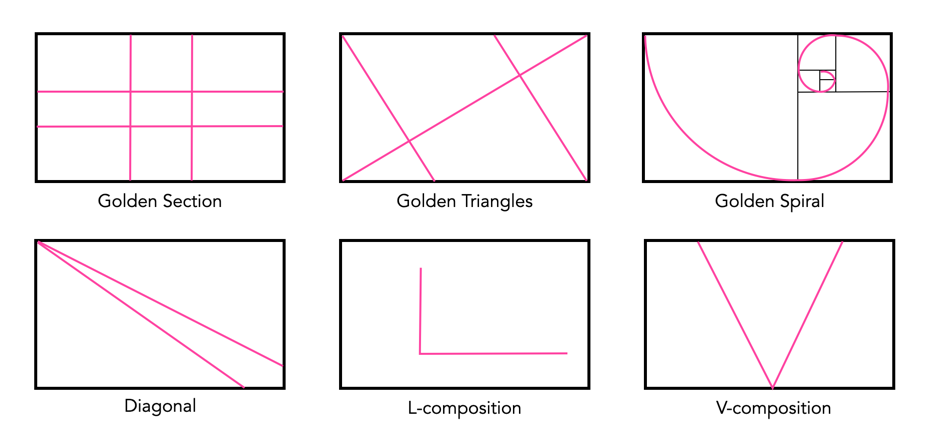

But is it the most optimal means of composition? Hardly. The rule of thirds is not mandatory and when the composition demands it, it can and should be violated. In reality it shouldn’t even be perceived a rule, but rather a guideline. Some photographers believe that an over reliance on this method of composition can lead to boring photographs. Of course the “rule of thirds” isn’t the only method of composition, indeed there are numerous others, some of which are shown in Figure 3. The best composition method is the one that best suits the particular scene being photographed.