The idea of “bokeh” originated in Japan, the western term derived from the the two Japanese Katakana characters bo and ke, “ボケ”, which roughly translates to “to be out of focus”, “to be blurred”, or “out-of-focus blur”. The term made its western debut in 1997 courtesy of Mike Johnston in Photo Techniques magazine. For a long time, there was little or no interest in the concept, but in recent years, and with the use of vintage lenses on digital cameras, it has come to the forefront. Maybe too much so.

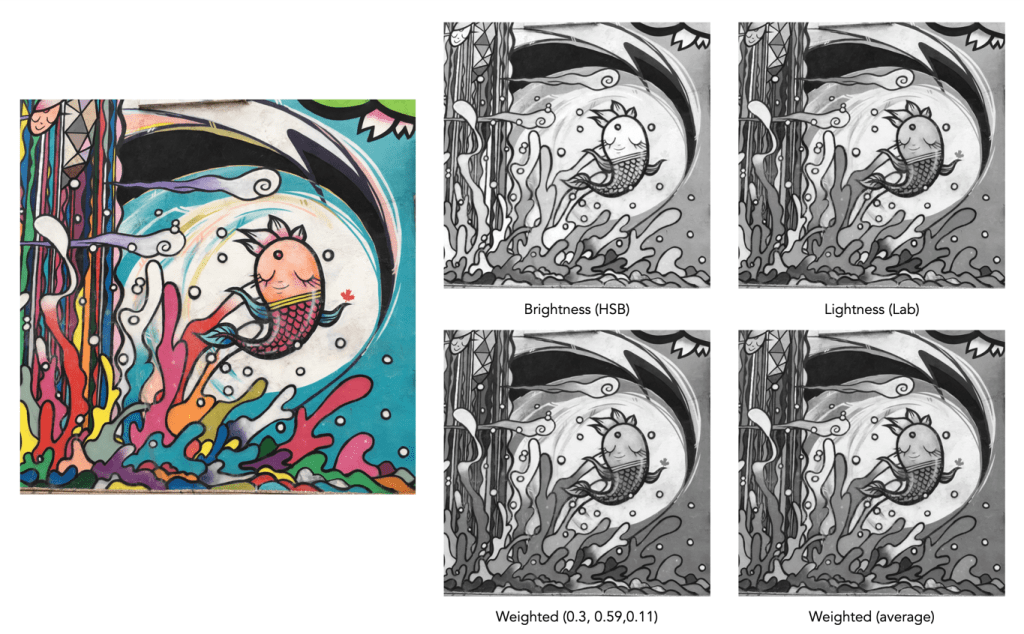

All images contain blur in one form or another, typically in the form of out-of-focus (OOF) regions. The blur that separates a subject/object from its surroundings is the result of shallow depth-of-field (it can occur behind or in front of the subject/object). In many cases OOF regions contribute to the overall aesthetic appeal of an image, either by isolating an object/subject or setting a particular mood. Bokeh is often defined as the quality and aesthetic appeal of the OOF regions of an image, as rendered by the camera lens. Sometimes a particular lens will produce exceptional out-of-focus regions, while others will produce harsh OOF in the same scene.

One of the problems with the term is that it is somewhat imprecise, and often used inappropriately. The Japanese boke is a very subjective, aesthetic quality, so there is no real way to describe it beyond its definition. An article which appeared in the same issue of Photo Techniques, “Notes on the Terminology of Bokeh” by Oren Grad explored many of the Japanese terms used to describe bokeh. For example when a lens diaphragm with six blades is stopped down the iris may become visible in the form of surudoi kado (sharp corners), resulting in ten boke (point bokeh). But there is no indication that this is necessarily “bad bokeh”. Amongst many terms, bokeh could be sofuto (soft) or katai (hard), hanzatsu (complex) or kuzureru (breaking-up). Some of the terms relate purely to out-of-focus highlights, but bokeh is the overall effect as well.

It is true that bo-ke plays a large role in Japanese photographic culture, where it is an aesthetic quality, but bokeh is not just about the optical aesthetics – there is such a number of differing variables at play. Bokeh can even be different within a single lens, changing with a change in aperture or focus, the nature of the subjects/objects in the frame, and lighting conditions. Bokeh, like photography itself is often an enigma of chance. Now it seems like every lens review has to include a lenses ability to produce bokeh. But we are not talking about the bo-ke of Japan, we are talking westernized Bokeh… dreamy, creamy, soapy bubbles. All these pictures with orb-like features in them. Blah! Smooth, or “creamy” blur is desirable, orbs with defined edges are undesirable, or “bad” bokeh.

“Bokeh is not a natural artifact, because humans don’t perceive it outside of photography.”

I mean, I don’t begrudge people for taking these surreal pictures, but real bokeh is not all about these glowing orbs. And what exactly does “buttery” mean? Or creamy? Sorry, these are ridiculous terms. You can’t describe out-of-focus regions as buttery, or creamy. Shortbread biscuits are buttery, but describing bokeh as buttery is weird. Is it meant to signify smoothness? Because butter is only smooth when left at room temperature (and even that is tenuous). The same with using “creamy” as a descriptive word. Mash potatoes can be creamy, as can ice-cream, but not bokeh. Creamy and buttery are not words that describe smooth, they describe mouthfeel and taste.

Most people who use the term bokeh, really don’t know what the term means, and spend too much time trying to create it, rather than letting it occur naturally, usually at the expense of the subject within the image.