There is a lot of information about photography on the internet, and honestly for the beginner it can be overwhelming. The task of deciding on a digital camera is hard enough without content creators prattling on about things you probably don’t need. Here are a few pieces of gear to steer clear of – from the pure perspective of the amateur photographer.

① Full-frame cameras − The ubiquitous dSLR, or “digital SLR” is an extension of 35mm film cameras, hence the reference to “full-frame” (sensors are 36×24mm). They have been the mainstay of professional photographers for the past two decades. But they are not something that an amateur photographer should even consider. They are large, heavy, and prohibitively expensive. The size alone makes them inconvenient for things like long-term travel. In an age of mirrorless cameras with good APS-C sensors they honestly just don’t make a lot of sense. Even the big manufacturers such as Nikon have shifted their emphasis away from dSLRs. There are situations where dSLRs are more of an advantage – low light, a larger sensor, wildlife an sports photographer, none of which are really the concern of the amateur photographer.

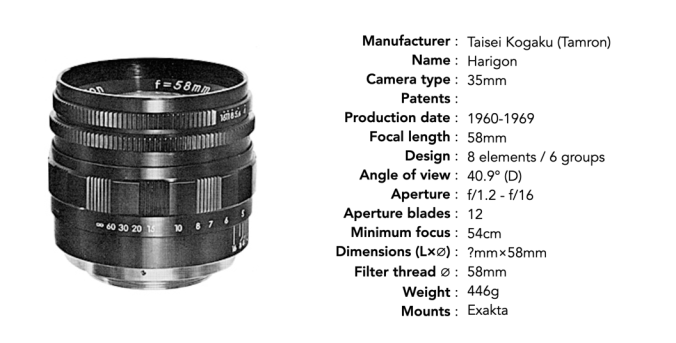

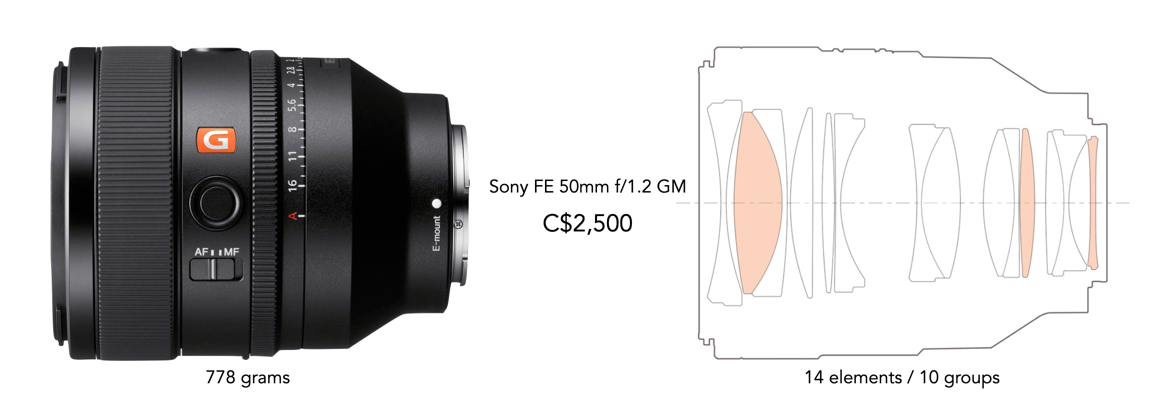

② Fast lenses − What is a fast lens? I would probably categorize it as a lens with a speed faster than f/1.8 up to f/1.2. They contain a lot of glass, are heavy, and expensive. But frankly most people don’t need these lenses. They are perfect for people who shoot a lot at night, or in low-light settings, but slower lenses can also be used in these scenarios. (I wrote a whole post on whether you Should you buy a superfast lens?, and Are modern ultrafast lenses useful?)

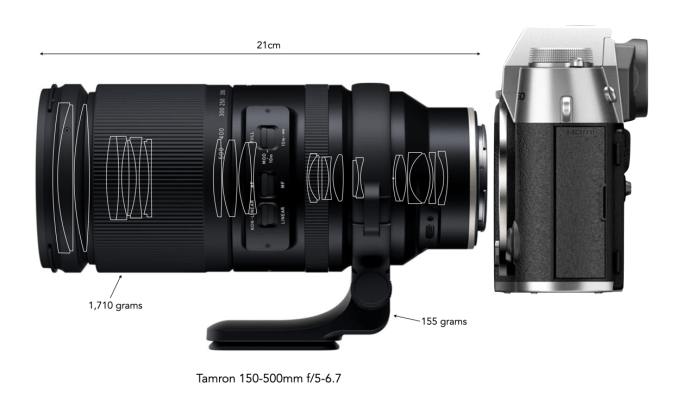

③ Super telephoto zooms − The zooms offer focal lengths like 100-500mm, and are very versatile, just not for the beginner. It’s tempting to consider, but not actually that useful unless you have a specific need, i.e. sports and wildlife photography. In many cases it is just too much zoom. For example landscape photography doesn’t always gel well with focal lengths beyond say 200mm, because there is a tendency to loose perspective, which is the whole point of many landscapes. The other problems are pretty obvious – size and weight. Of course here there is another benefit of mirrorless APS-C cameras, smaller zooms. The Tamron 150-500mm lens for Fuji-X seems amazing (225-750mm eq.), but it contains 25 elements, and weighs 1.71kg – try lugging that around for an extended period!

④ Filters − There are a lot of really good filters which do things like reduce glare, and unwanted reflections, and correct or enhance colours. For example polarizing filters are useful when shooting landscapes in sunny locales, they darken skies, and make colours stand out more. Neutral density filters reduce light hitting the sensor, but doesn’t affect image colours. But it may be best to focus on taking good photographs, and conquering exposure before adding filters into the fray. P.S. UV filters are basically pointless because most sensors aggressively filter UV light. Save the filters for when you gain a little experience.

⑤ Tripods − Most people do not need a tripod. They are super useful for taking stills at home, or when you need to use a super-slow shutter speed, but otherwise they are a bit of a door-stop. They are not at all useful for travel, and overall just aren’t worth the effort. The only ones that can be somewhat useful are the mini variety such as the Manfrotto PIXI (but honestly avoid the Gorilla-type flexible tripods).

⑥ Camera body upgrades − Avoid the trap of upgrading your camera body every 1-2 years. A camera body should last a good amount of years, so there really is no need to consistently upgrade. If you are at the point of considering which camera to buy, save some money and buy an older version of the camera. The reality is that technology has plateaued somewhat in digital cameras, and there isn’t going to be much difference between two or three generations of a camera (except the price). Advanced features aren’t that useful if you are still grappling with the basics.

⑦ A light meter − If you have a film camera, then a light meter might be a must. But in the case of digital cameras, having a dedicated light meter may not be necessary. Good ones are expensive, and take up room. It’s easier to trust the light meter in the camera, or for film cameras use a light meter app such as Light Meter Ultra.

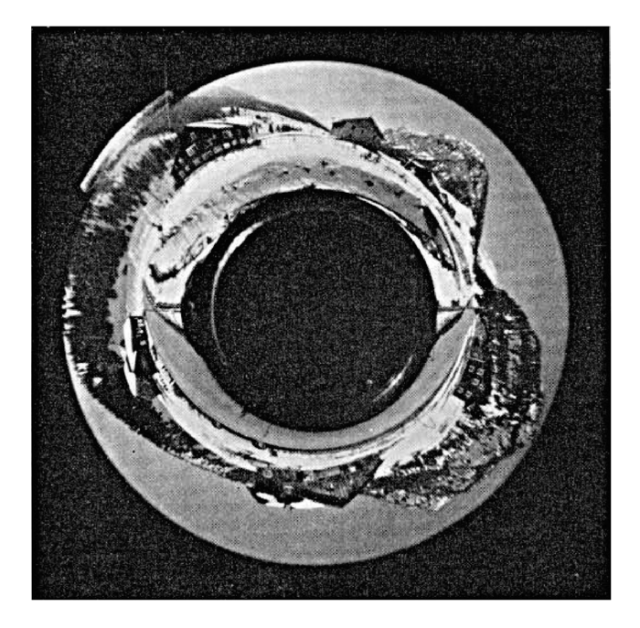

⑧ Lenses you don’t need − It’s hard not to want all the lenses that photographers review online. They look cool, and it would be fun to play with them right? Especially the myriad of inexpensive lenses now on offer. But here’s the thing, most of them you won’t use on a regular basis. Fish-eye lenses are a good example. They are fun and creative because they provide an ultra-wide view of the world. But the caveat is that reasonably priced ones are typically manual focus, and there are very few applications (unless it is a rectilinear fish-eye). There is probably a good reason that manufacturers like Fuji don’t have any fish-eye lenses.

Photography can get to be an expensive hobby, and buying things you don’t need can be a slippery slope. Many of these things I learned the hard way. Buying lenses that I thought I would need, but ended up sitting on a shelf. Think of it this way – every piece of gear that you buy should solve a problem of some sort, but not just a 1-2 instances, a problem you encounter a lot. If you are really interested in a lens, then try and rent the lens before buying to actually see if it is as useful as you think.

Ultimately a new lens or any other gear doesn’t replace the need for knowledge and experience, or frankly will it help you do something if you don’t really know what you are doing.