Novoflex is a German maker of lenses and camera accessories (macro bellows, tripods, tilt-shift bellows, etc.). It was founded in 1948 by photographer Karl Müller Jr. In 1949 the company produced the reflex housings for Leica, which allowed SLR lenses to be modified for use on Leica cameras. These were initially marketed under the name Reproflex, until being changed to Novoflex in 1950. From 1954 housings were also made for Contax cameras.

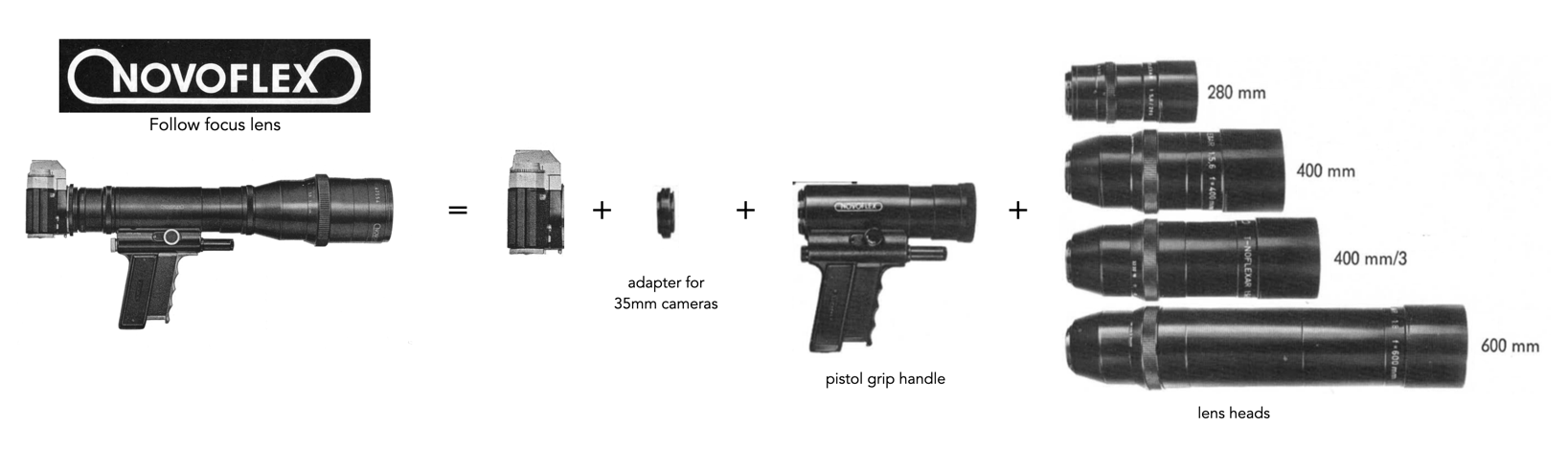

In 1956 they started production of their first lenses, the Novoflex Follow Focus lenses. The Follow Focus lens system was interesting because it included a pistol-grip focusing device that allows the user to go from infinity to minimum focus in a split second. Essentially it provides one-handed focusing. According to the company this was useful for “wildlife subjects in full flight, sports, the fleeting moment, the unexpected are unusual picture opportunities that must be taken at peak-action.”

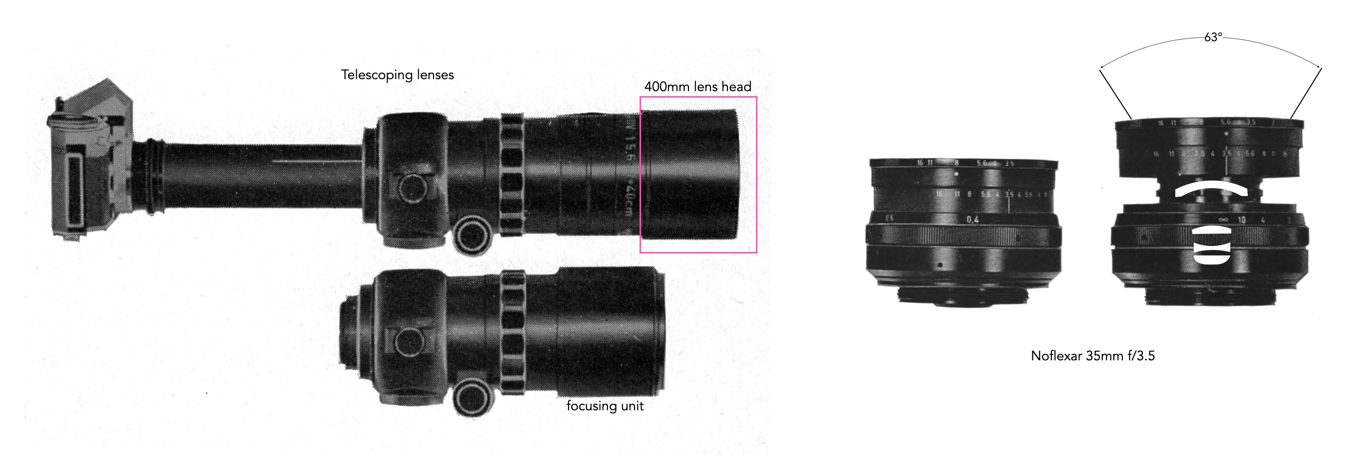

This was followed in 1960 with nesting telephoto lenses, advertised as ‘telescopic tele lenses’. These were designed in order to make telephoto lenses easier to transport, being able to collapse to half their size. The focusing unit could be equipped with lens heads for 400mm and 640mm. In 1962 the company introduced the ‘2-in-1 lens’, 35mm f/3.5 Noflexar, a macro wide-angle lens with a focusing range from infinity to 2.75”, and a reproduction ratio of 1:2. In 1969 the company started making automatic bellows devices. The company had an extensive range of ancillary products for many camera systems. This included a wide-angle macro lenses, bellow units, follow-focus lenses, slide copiers, and associated coupling adapters.

Novoflex is still an active company, producing photographic accessories such as auto-bellows, tripods, macro systems and camera-lens adapters.