This FAQ deals more with the “tech” side of things. Vintage cameras are mostly mechanical, i.e. they are filled with gears and doohickeys of all sorts.

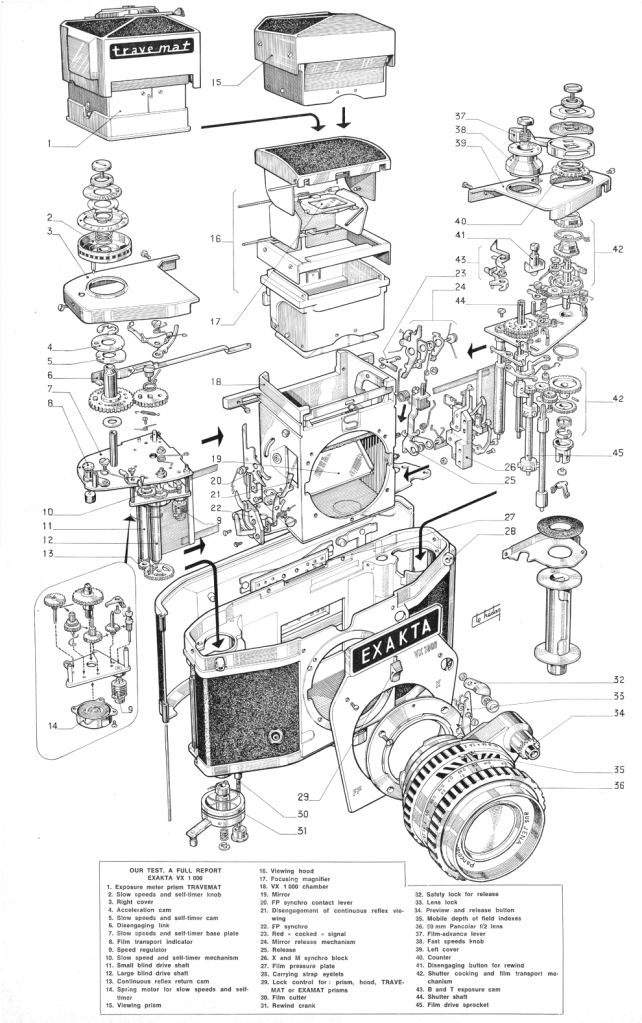

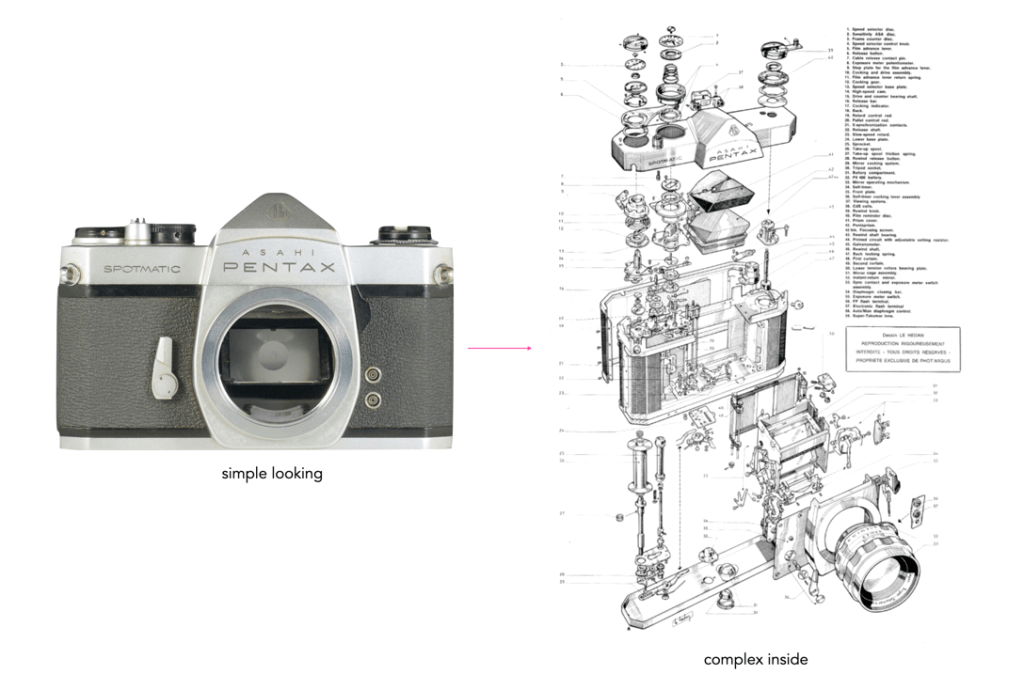

How complex are vintage cameras?

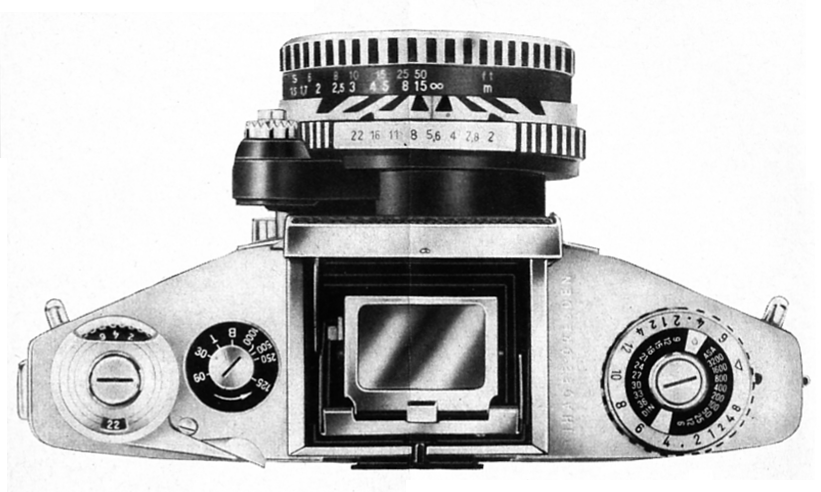

Quite complex, at least from a mechanical perspective. The earlier rangefinders may have been somewhat less complex, but as cameras attained more features, the mechanical complexity increased. They are a world away from the early plate cameras with very moving parts. In some respects electronically controlled cameras can often have simpler designs.

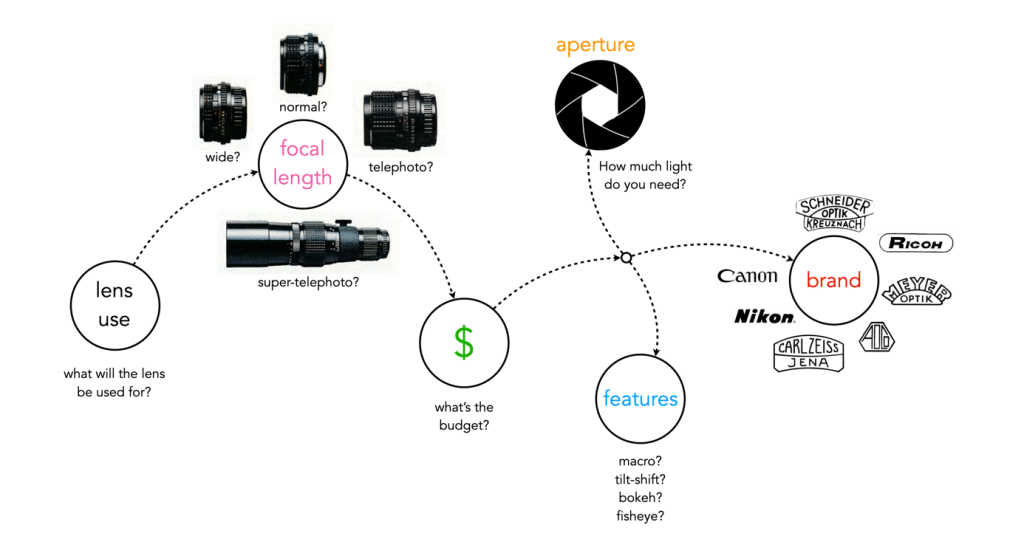

Which brands are most dependable?

This is really hard to pinpoint. You really have to go off reliability, popularity, and reviews. Every manufacturer created good SLRs, and ones that were less that stellar. The less dependable cameras are often those that have known mechanical issues, obscure mechanisms (e.g. “new” shutter mechanisms, or materials that just didn’t work), or have poor usability. If this question is asked on some forum, everyone will have a different answer.

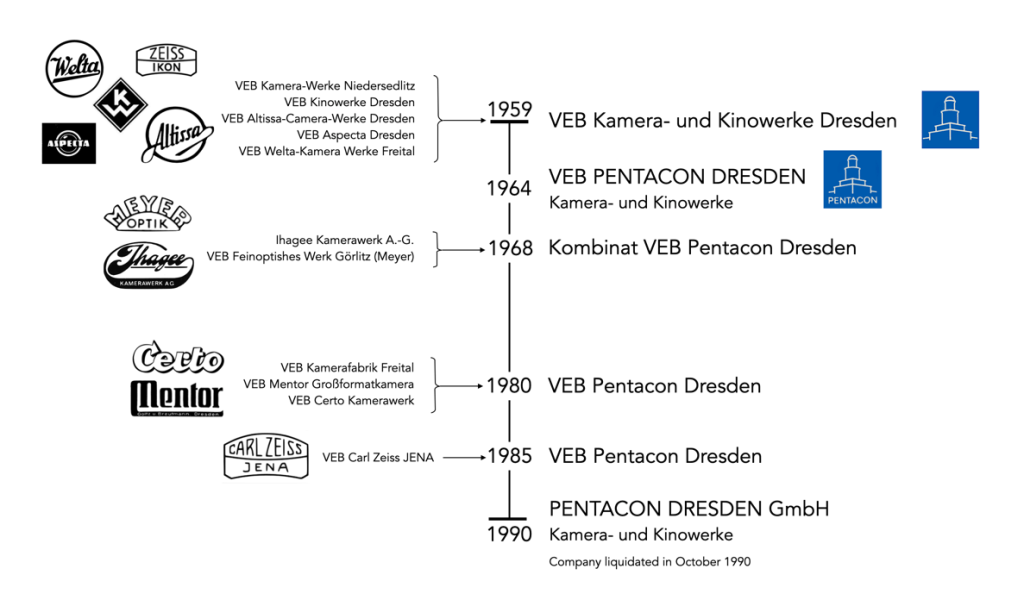

Which brands to avoid?

I don’t like to pigeonhole brands, but for the novice I would honestly avoid East German and Russian SLRs. There should be a lot of these cameras, but in reality there often aren’t, perhaps because they haven’t stood the test of time. The exception is the manual Ihagee Exakta cameras, which generally are quite good from a mechanical viewpoint.

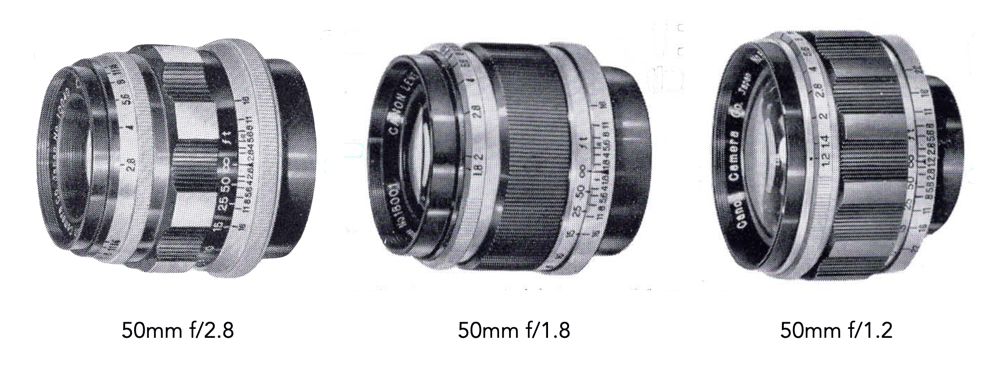

What’s the most important technical issue with vintage cameras?

Arguably the most critical things have to do with the shutter. Shutters are generally constructed of light-tight cloth, metal, or plastic curtains, all of which can be damaged. Does the shutter actually work properly on all shutter speeds, i.e. does it open and close, and not get hung up somewhere? In some cameras the shutter will work fine for fast speeds and perhaps get hung up on one or two of the slower speeds. You can usually test this by opening up the back of the camera and checking the shutter at each speed setting. More critical may be whether or not the shutter speeds are accurate. Again some may be, others may not be.

Are batteries an issue?

There are vintage cameras that use batteries, mostly those that use meters of some sort, or contain electronics. Some vintage cameras use Mercury-oxide batteries which are a problem, because sometimes can’t often be satisfactorily replaced (they were banned in the late 1990s). Also, sometimes even when you find a battery, aging electronics can lead to issues. I have a Minolta X11 (specified to use S76 1.5V “silver-oxide” batteries) which works well, except for one thing – the batteries drain really quickly. This was a quick fix though, only add the batteries when the camera is actually being used.

Are SLR cameras repairable?

Yes, but these days it is sometimes hard to find people that fix them, and it can be expensive. Some repair specialists just remedy specific camera brands. It is also an issue of how readily parts are available – if you have a camera where a lot were made, (say 500,000) it is obviously easier to find donor cameras to provide parts than it is a vintage camera where very few were made. A film camera CLA (Clean, Lube, Adjust) can cost anywhere from C$150-300. In some cases it may be preferable to pay more for a certified camera rather than go through the hassle of repairing an inexpensive one.

Can I fix a camera myself?

Hmmm… yes and no. Let me put it into context. If a camera is cheap you could try and fix it, depending of course on the complexity of the issue. To do this, you need to have the right tools, and probably a camera manual. The problem is that sometimes the sheer age (50-80 years) can mean things are seized up, and un-seizing can sometimes lead to things breaking. I would honestly not go down that path (having tried fixing something simple, it just broke something else). It takes a lot of patience and quite a bit of knowledge to pull things apart and put them back together in working order. Even manual cameras are complex – the innards are a haven of interwoven mechanical things. Open a camera at your own peril.

Are light meters an issue?

Invariably yes. Some of the meters, like the early selenium meters can often work quite well, whereas the Cadmium Sulfide (CdS) meters may not work as well. Sometimes cameras will be advertised as “meter not functioning”. Sometimes due to age, the light meter may not be that accurate anyway, so it might be best to use an external light meter, or even a digital one.

Are there issues with electronic 35mm SLRs?

Yes, electronics don’t always stand the test of time well. Electronics tend to be adverse towards moisture, and dust, which will find their way into a camera and cause issues. It may be possible to find (or even manufacture) mechanical part replacements, electronics are another thing altogether. That being said, electronic cameras are usually quite reliable.