Zunow was a Japanese company best known for it’s innovation in superfast lenses. During the last few years of its existence, the company designed a couple of camera’s including a prototype of a Leica copy, the Teica, and their first 35mm SLR, the Zunow Pentaflex or ‘Zunowflex’. Work on the camera supposedly began around 1956, but it was only produced for a short time, from 1958-1959). The Zunowflex had a compact design, inspired by the likes of the Miranda T, or even the Praktina.

The design of the Zunow Pentaflex was initiated by Kiyoshi Arao, the managing director in charge of technology who had been transferred from Chiyoda Kogaku Seiko Co., Ltd. Zunow Optical was originally a lens factory with no experience in camera bodies, and Arao himself had little experience with 35mm SLRs, so went on to study the Miranda. Arao would leave the company due to conflicts around the time of the camera’s release (joining Mamiya Optical). The camera was first announced in the April 1958 issue of the monthly magazine Shashin Kōgyō.

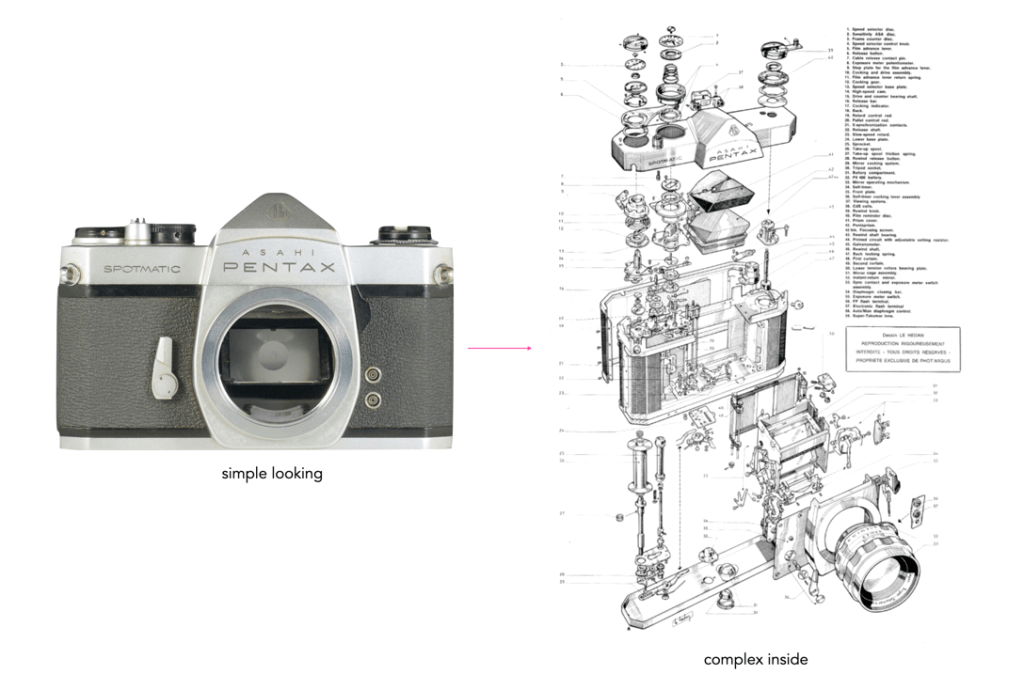

This camera brought solutions to many of the issues outstanding with SLRs together into one camera. It was a very aesthetically pleasing camera, with a streamlined look, that would become normal for cameras in the 1960s. The elegant look was designed by Kenji Ekuan from GK Industrial Research Institute. Ekuan was an industrial designed best known for designing Kikkoman’s iconic soy sauce bottle, and a series of Japanese trains. The design was started from a completely new idea, taking the spirit of ancient Japanese “Noh” as its model, combining complex mechanisms into a simple and concise form.

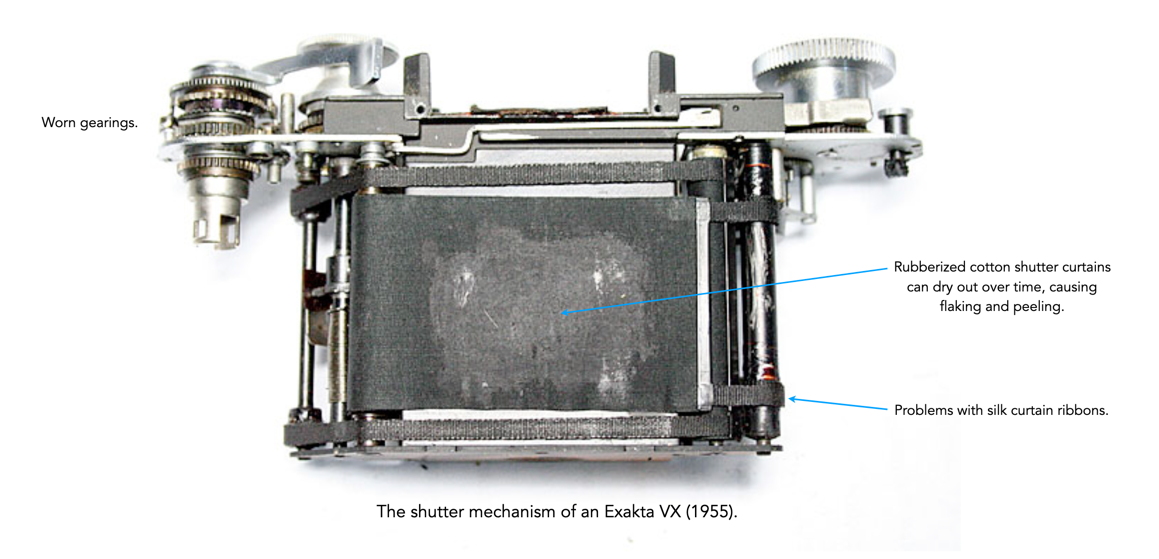

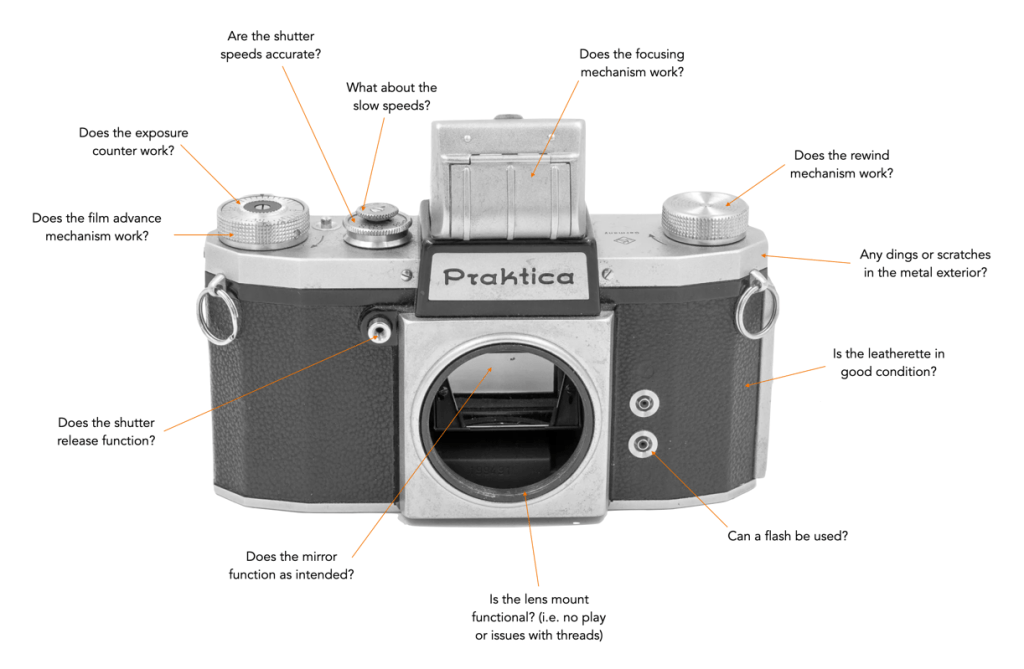

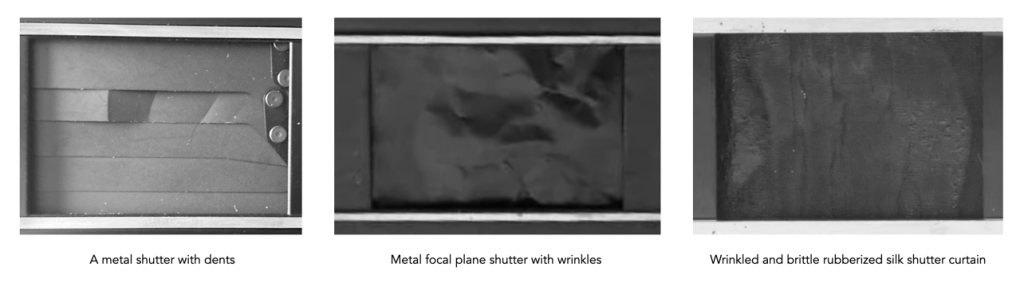

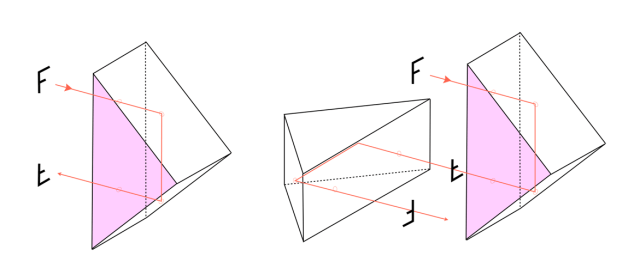

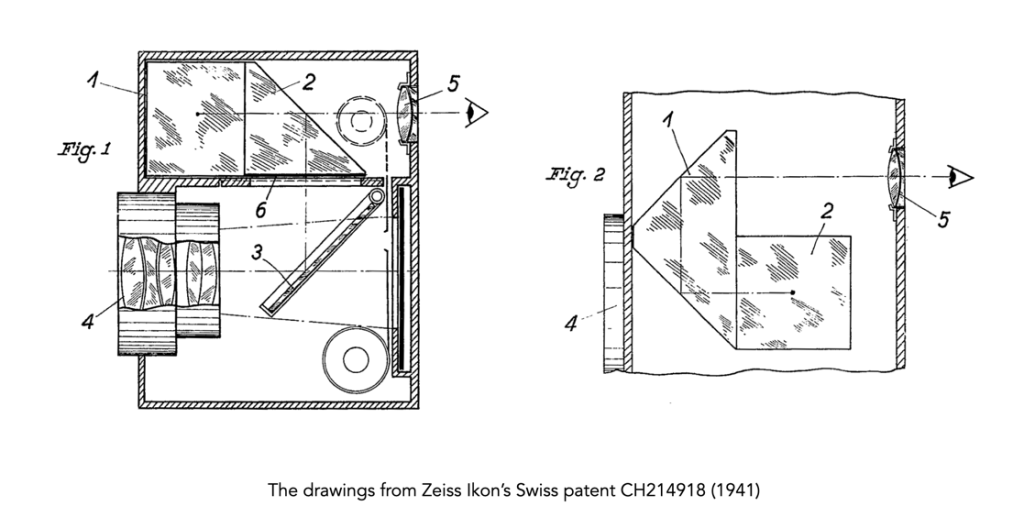

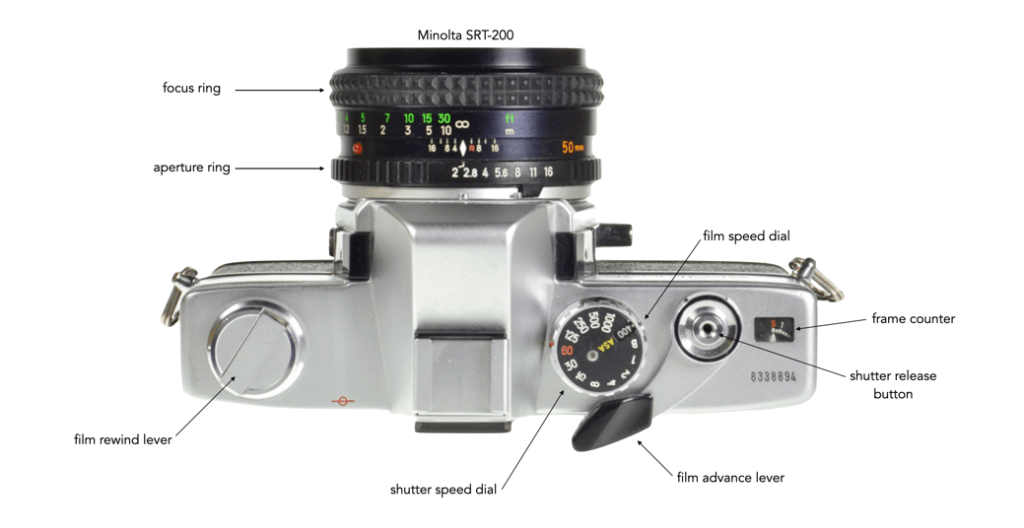

Where it broke from convention was the fact that the shutter release was front mounted, similar to how the Exakta and Miranda cameras were laid out, and the speed dial was situated beneath the wind lever, a concept which didn’t appear until much later on the Canon AE-1. It had a removable pentaprism, and interchangeable focusing screens. Supposedly a waist-level viewfinder was also available. It also had a right-hand front shutter release, and a lever wind, not found on many SLRs of the period (except for the Exakta which was left-handed, the Mecaflex, and the Asahi Pentax). The camera had a focal-plane shutter with speeds from 1 to 1/1000 sec, plus B.

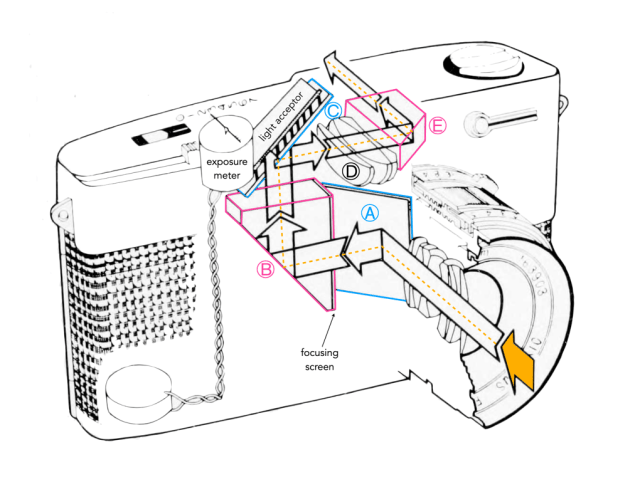

It was the first Japanese camera to have an internally coupled automatic lens diaphragm, the “ZUNOWmatic” diaphragm system, when most cameras of the era had a pre-set system, meaning a lever had to be moved to open the diaphragm after the photograph had been taken. It worked like this: when the shutter release is triggered, “the automatic diaphragm actuating ring revolves and trips the auto-diaphragm “tail” of the lens mount, diaphragm closes down to previously determined aperture, mirror springs up out of the way, Shutter operates, mirror then returns to normal “seeing” position, diaphragm actuating ring revolves again, kicks the pin back into position and reopens diaphragm to maximum aperture” [1].

The instant return mirror, was something Zunow called the “Wink Return”, which supposedly was quiet, or put another way – “quiet it is, silent it is not” [1]. In its marketing material the company suggested that traditional SLRs had issues with mirror return, i.e. there is a shock, and the sound of the shutter is loud. The “wink Return” was suppose to eliminate unpleasant noise and shock with almost no blackout effect. The lever was considered by some to be “heavy”, but the shutter release is “surprising light” [1]. There is a single shutter speed dial, with equally spaced speeds (which few SLRs had), which allowed for the choice of intermediary speeds. Another unique feature is an internal synchro-switch which automatically sets FP or X sync as shutter speeds are changed from fast to slow. The downside is that the camera was heavy at 620g.

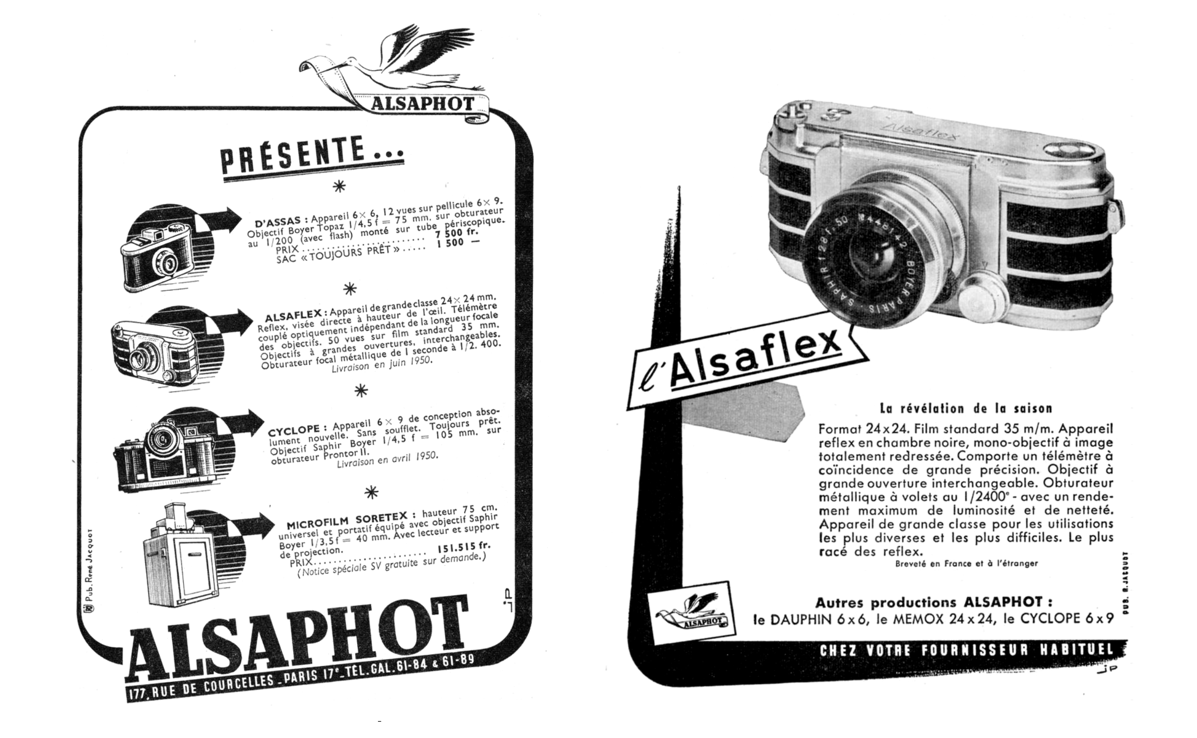

One potential limitation of the camera was its proprietary breech mount, and a range of only six lenses: 35mm f/2.8, 50mm f/1.8, 58mm f/1.2, 100mm f/2, 200mm f/4, 400mm f/5.6, and 800mm f/8. Only the lenses 100mm and shorter had auto diaphragms. There were lens mount adapters to allow the use of M42, Exakta and L39 lenses, likely reducing the need to produce an entire range of lenses. Supposedly the lens provided with the camera was the Zunow 58mm f/1.2, which would have been the fastest SLR lens of the period (the only evidence of its existence seem to be the ads in Figure 2).

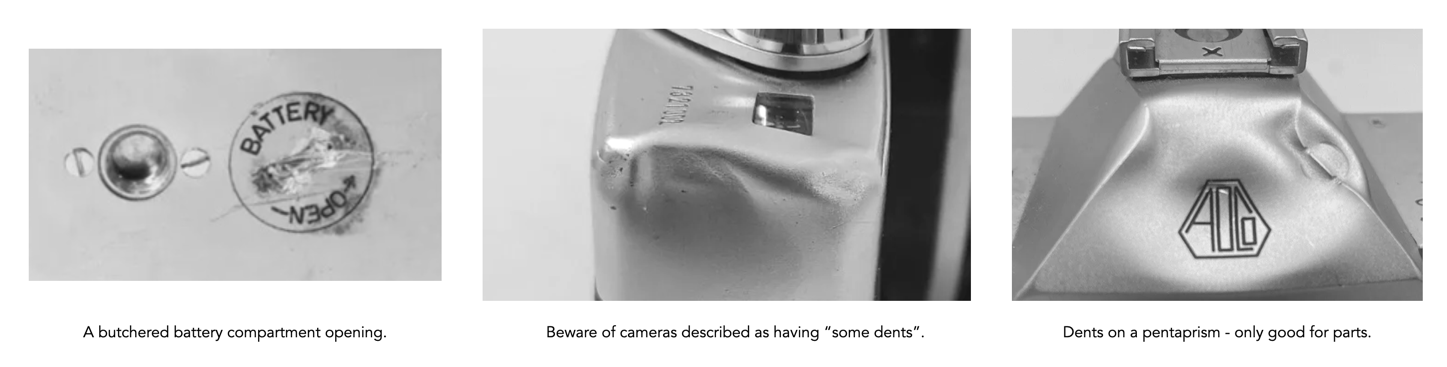

However in all reality there were issues with the camera. Adding new features to a camera implies that a substantial amount of testing must be performed before mass production commences. It has been suggested that hundreds of cameras were sold, however a lack of quality control meant many were returned [2] (this may be in part because most of the parts were outsourced, with the factory only doing assembly [3]). Other parts of the system, such as other interchangeable viewfinders were also lacking. There were also functional problems with the camera, for example the fully automatic aperture was slow, resulting in incidents of the aperture lagging behind the shutter [2]. Of the cameras existing today apparently few work perfectly [2].

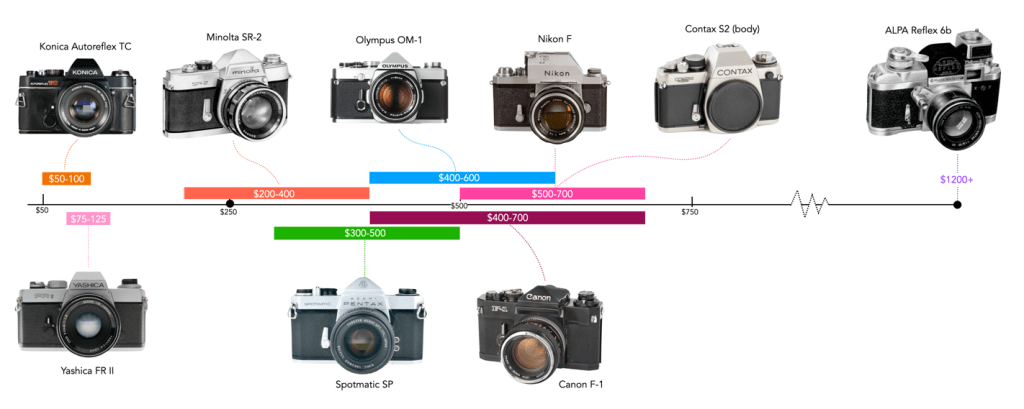

The camera was only sold in Japan, and in total only about 500 were produced (at the rate of 8 cameras per day [1]). In 1959 the speculation was that it would be expensive in the US, as the Zunow + 58mm f/1.2 lens sold for US$300 in Japan. However Zunow was in a poor financial situation and was not able to capitalize on the design, closing the company in 1961. These cameras are now extremely rare. Auctions, where they occur then to suggest prices of around the US$20,000 mark.

Specifications:

Type: 35mm SLR camera

Manufacturer: Zunow (Japan)

Model: Zunowflex

Production period: 1958−1959

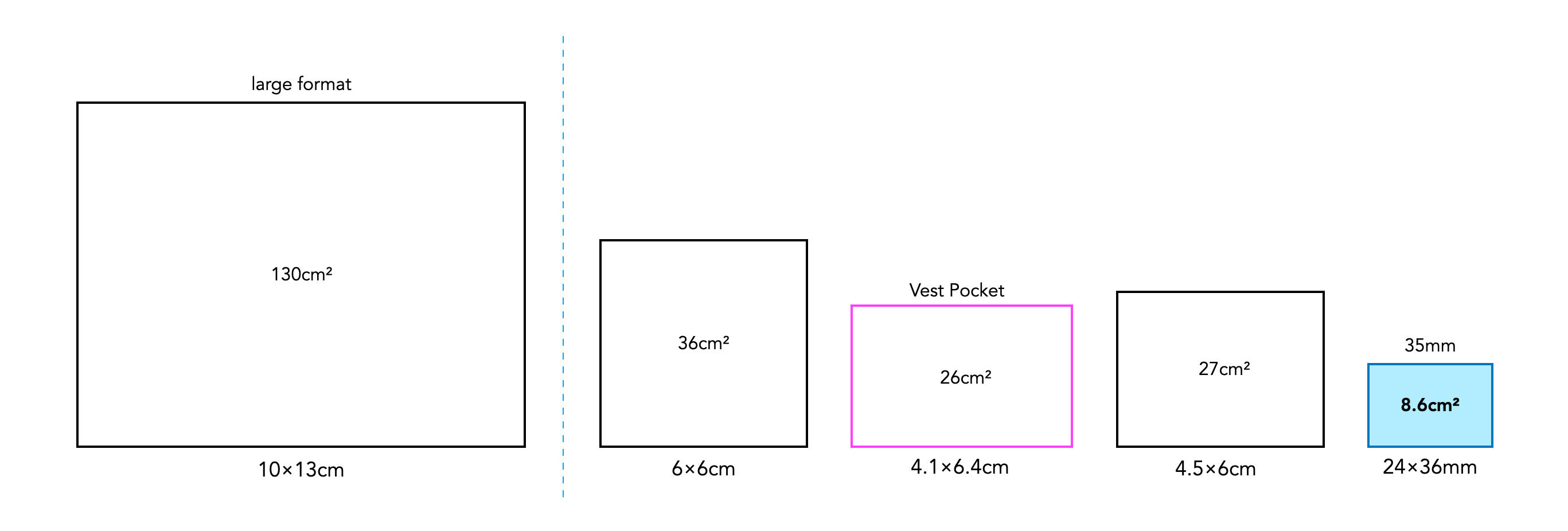

Format: 24×36mm on 135 film

Lens mount: breech

Standard lens: 5.8cm f/1.2, 5cm f/1.8

Shutter: focal-plane, single-axis non-rotating dial type

Shutter speeds: 1 to 1/1000 sec., B

Viewfinder: SLR with non-removable pentaprism

Mirror: “Wink return” system

Exposure meter: −

Flash synchronization: FP, X automatic switching

Self-timer: −

Aperture control: Instant opening and closing type built into the body, fully-automatic

Film advance: 180° operation lever wind, prevention of double exposures, automatic frame counter

Weight/dimensions: 615 grams / 144×88×56mm

Further reading:

- Tsuneo Baba, “Zunow: Indication of things to come in 35mm single-lens reflexes?”, Modern Photography, 23(4), p.110 (1959)

- Kosho Miura, “Systematic Survey on 35 mm High End Camera – History from Leica to SLR”, National Museum of Nature and Science Survey Reports of Systematization of Technology, 25, pp.55-56 (Mar. 2018)

- Interview with Suzuki Takeo, CEO of Ace Optical (son of Zunow’s president), May 2006 (PDF)