This past covers more aspects of buying a vintage camera in FAQ form. When it comes to 35mm interchangeable-lens cameras there are two categories: rangefinder and single-lens-reflex (SLR). This FAQ is concerned with SLRs because they became the dominant form of SLR camera found on the used market.

What are the best vintage cameras?

Identifying the best vintage camera is very much a subjective thing. Unlike lenses though, which are often chosen for the aesthetic appeal they impart upon photographs, cameras are all about functionality. All cameras really serve the same purpose, as a vessel to hold the lens, and film, and control the process of taking a photo. So the best vintage cameras are often those that achieve this in a way that doesn’t compromise functionality. They should be simple to use, aesthetically pleasing, ergonomic, and don’t suffer from a series of maladies, e.g. shutters that could imminently fail, poor engineering or manufacture etc.

Which camera types are best?

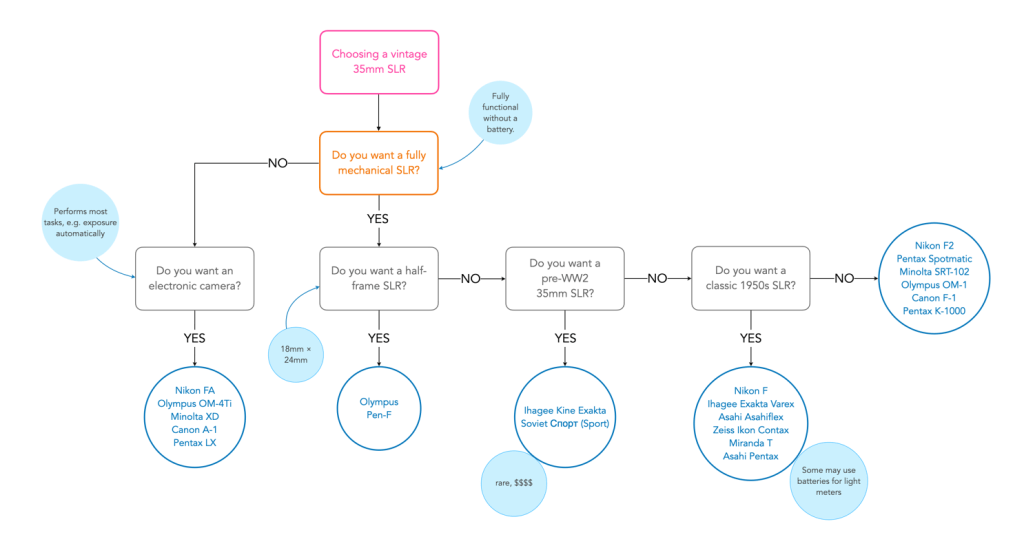

It really depends on what sort of features are required, and perhaps what sort of lens mount (not all lens mounts are inter-compatible, and it is hard to find adapters for film cameras). Do you want fully manual, semi-automatic, or fully electronic? Do you want a built-in light meter (which is tricky because many don’t work anymore)? Then you have to figure out which ones are problematic from some functional viewpoint, e.g. problems with shutters, or flaky electronics. For example Olympus made 14 major models of manual focus SLR in the period 1972 until 2002, and two automatic models. The OM-707 was an auto-only camera, and somewhat of a disaster from a usability perspective. The Olympus OM-4Ti (1986-2002) is considered by many to be best film SLRs money can buy.

What is the most versatile camera mount?

In reality, M42 is likely the most common lens mount, at least up until the early 1970s. There were a lot of lenses made for this mount from a myriad of manufacturers. There were also a bunch of cameras that used it as the mount. Next in line might be the Exakta mount.

Can film cameras use lenses from other brands?

Unlike mirrorless digital cameras, which have a short focal flange distance, allowing for adapters to suit a bunch of 35mm film lenses, the same is not true for film cameras. Some cameras can use lenses with other mounts, many can’t. For example the Minolta cameras with an SR-mount can use M42 mount lenses, because the flange distance on the camera (43.50mm) is less than that of the lens, allowing an adapter to convert the M42 to SR-flange (MD,MC) – however the opposite is not true.

Do some people buy cameras because they are aesthetically pleasing?

Yes. Some people love how cameras look, even if they don’t function that well. Form over function is a real thing for some people, of course beauty is always in the eye of the beholder.

Why were some SLRs unsuccessful?

Sometimes cameras didn’t sell that well, and as a result weren’t that successful. This was usually down to poor choices in the design of the camera. A good example is Rollei which had its own bayonet mount lens system known as the QBM – proprietary lens mounts means a smaller choice of lenses. Poor usability, or finicky mechanical features often lead photographers to abandon a camera. Sometimes it can be poor aesthetics, as with the case of the Minolta Maxxum 7000, although to be honest requiring photographers to dump all their lenses in favour of a new system with autofocus, probably wasn’t the best idea.

What about brands?

There are three major categories of vintage camera manufacturers. The first are landmark manufacturers who got into the game early, and focused heavily on SLRs. They likely had a start in 35mm rangefinder cameras. This means manufacturers like Exakta, Asahi-Pentax, Nikon, and Canon. Pentax is the only one of the three that did not produce rangefinder cameras. Next are the companies that are second tier, i.e. they had a smaller footprint, made only SLRs or got into the game late. This includes Konica, Minolta, Fuji, Olympus, Topcon, Yashica, Petri, Mamiya, Miranda, Ricoh, Zeiss Ikon, KW, ALPA. Lastly are the companies who didn’t really do a great job with 35mm SLR – Leica, Rollei, Voigtländer. Each manufacturer produced both good and mediocre cameras, and so it really requires some investigation into the right brand.

Are Japanese SLRs better than German ones?

In all probability, yes. There are undoubtedly some good German SLRs, mostly from East Germany, produced in the 1950s and 1960s. West Germany really didn’t produce that many successful SLRs. Both countries struggled to produce SLRs that could compete with the ones produced by Japanese manufacturers. There are a few good German SLRs, e.g. the Contax S2, but the reality is there is likely better Japanese cameras that are way cheaper.

Should I buy a camera made in East Germany?

With the exception of Exakta cameras, many post-war Eastern bloc cameras suffer from lower standards of engineering, reliability, and in some cases poorer usability than West German and Japanese cameras. When they were new, this was less of an issue because these cameras were often sold for dramatically lower prices. However aging cameras can be fraught with issues. Check the reliability of any camera you are interested in.

Why are there so many Eastern-bloc cameras?

Cold hard currency. The communist-bloc countries needed currency, and one was to achieve that was to produce goods to sell in the west. Banking on Germany’s pre-war reputation for producing photographic equipment, this was a very lucrative option. Dresden, which ended up in East Germany, was once the European epicentre of photographic innovation. The cameras were often sold cheaply, thanks in part to Eastern-bloc government subsidies.

What’s are the best East German SLRs?

Anything in the Exakta range, or perhaps a Praktina, or Praktica IV.

What about the weird brand SLRS?

Oh, you’re talking about the small independent brands?

- Rectaflex (Italy, 1949) – over-engineered, heavy yet reliable, these cameras are expensive only because of their rarity.

- Alpa (Switzerland, 1942) – exacting, well-built cameras. Some models such as the 6c are extremely good cameras, although some are susceptible to shutter issues. Expensive, but provides a unique character, and high level of quality.

- Wrayflex (England, 1950) – the only commercially successful, English made SLR.

- Edixa Reflex (West Germany, mid 1950s) – moderate quality cameras made by Wirgin (Weidbaden), these cameras rarely operate for very long.

Why are there so few cameras not made in Germany or Japan?

This is in part due to a lack of interest in developing their photographic sectors. While the allies poached a lot of high-tech workers from Germany, particularly from the armaments sector, they didn’t relocate any photographic expertise, except from the Russian occupied zone in Germany to the US zone. The boom in SLRs which occurred in the 1950s was driven by cheap cameras and lenses coming out of East Germany, and the growth of the photographic sector in Japan. Countries like the US, UK, and France could not compete, or just didn’t have the ability to get into a market that was dominated pre-war by Germany.

What’s does “mint” mean?

This is a term used by some resellers to indicate that a camera is in near perfect condition, almost like it came out of the factory last week. In many cases it likely means the camera sat in its box, and was never used (if it comes with the box and instructions, even better). However just because it’s mint doesn’t always mean that everything will function the same as it did when it came out of the factory 60 years ago. Materials still may degrade, grease solidifies, and gears seize up.

What about electronically-controlled 35mm SLRs?

This is often a choice for people who don’t want to deal with a fully manual camera. This means any 35mm SLR where electronics aid in calculating things like exposure. This could range from something like an aperture-priority-only camera to an autofocus equipped, completely automatic SLR. The only problem with these cameras can be aging electronics. If the electronics stop working, you basically have a paper weight. Choose a camera that is well reviewed and barely ever gets negative reviews. Note that manual cameras often had light meters, but that doesn’t make them electronic cameras (a camera with a light meter can generally be used even if the light meter doesn’t work.)