I previously covered choosing a camera for travel, now I thought I would provide some insight into choosing lenses for travel, in the context of an amateur photographer. There are many varied opinions on this travel photography, although I have to believe some come from photographers who aren’t really amateurs. This post speaks more to the traveller, who I consider distinctly different to the tourist. The tourist is a person who is just there to take photographs, with little interest in knowing the story behind the objects in the scene. They just care that they photographed the scene. The traveller is intrinsically interested in what they photograph. There are many forms of tourist ranging from the person who takes photos with an iPad to that annoying person who is fully decking out with a full-frame camera with the largest zoom lens available.

Travel photography, at least for the amateur, can suffer from what is commonly known as overpacking. You think you are going to need a bunch of lenses and accessories, and you end up with a bag overstuffed with gear. From my own experiences, you never end up using half of it. More important may be a couple of lenses for the large camera, and a secondary pocket-size camera, something like a Ricoh GR III. This ancillary camera is perfectly suited to street photography because it is designed to do just that, in a more discrete way (and offers macro as well). But back to the lenses. The reality is that you likely only need 1-2 lenses, or if you prefer zooms, a single lens.

The best travel combo is a normal and an ultra-wide lens

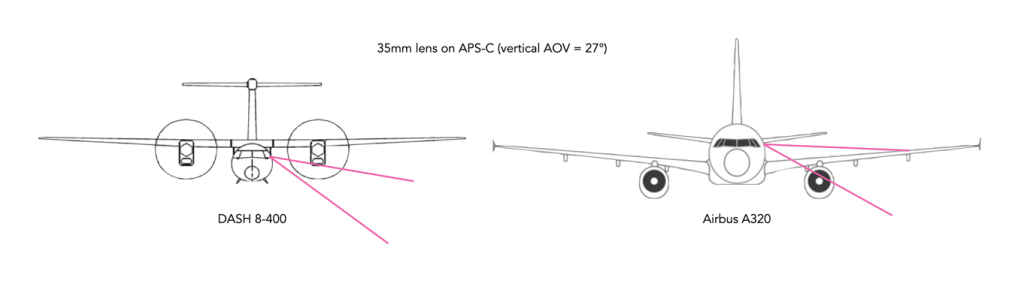

When you travel, you are trying to replicate in photographs what you see with your eyes. This means a normal lens, something in the range 40-55mm (or 26-36mm for APS-C), which provides roughly the same perspective as you see with your own eyes. A normal lens is good because it is inconspicuous, often quite compact, and quite adaptable to street photography. The faster normal’s also have the added benefit of performing well in low-light conditions, for example museums where flashes are often prohibited. For example with the Fuji-X system, a good choice might be a 35mm f/2 R WR, which provides a low-cost, weather-resistant normal lens (US$400, 170g), or the faster 33mm f/1.4 R LM WR (US$800, 360g).

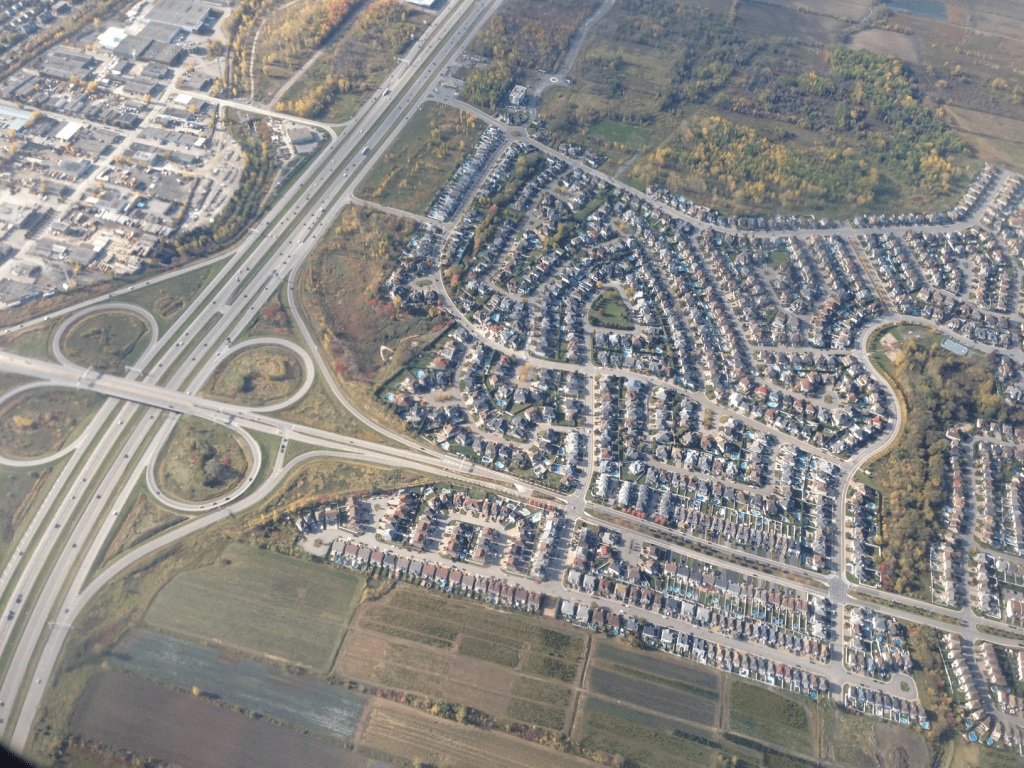

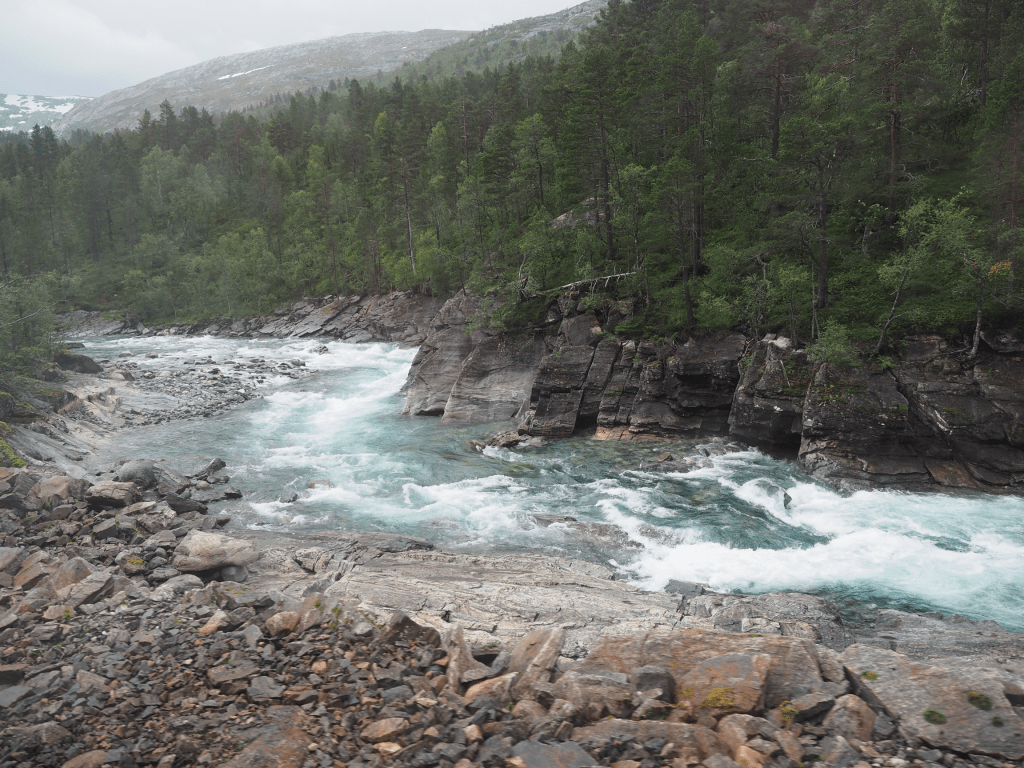

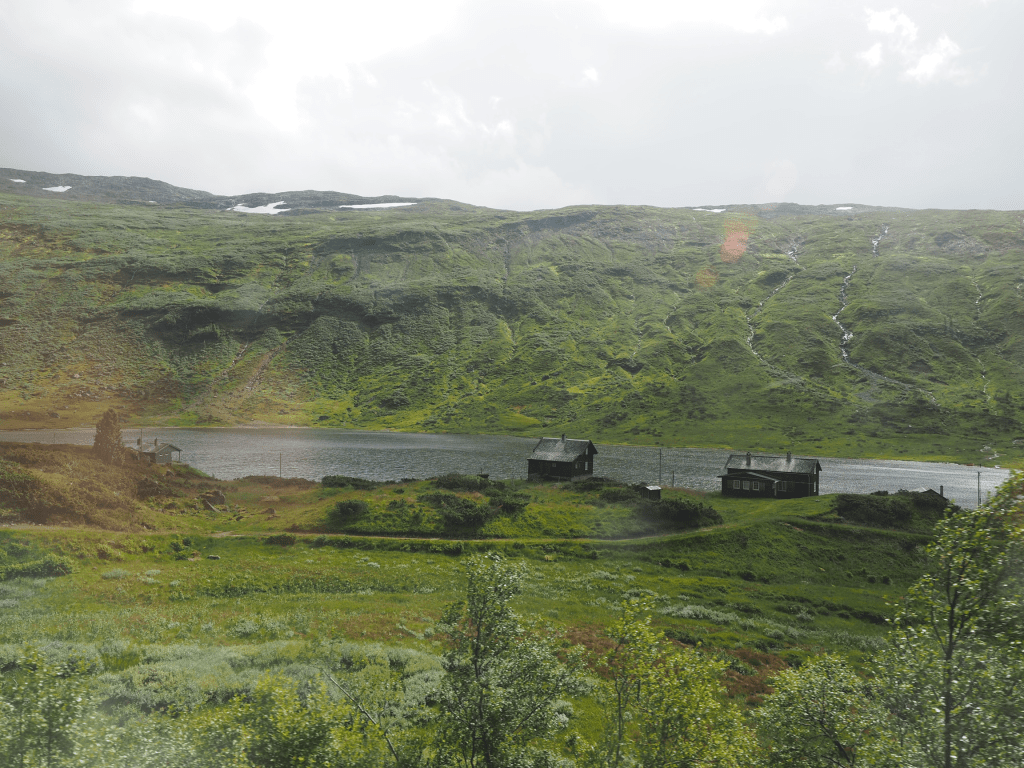

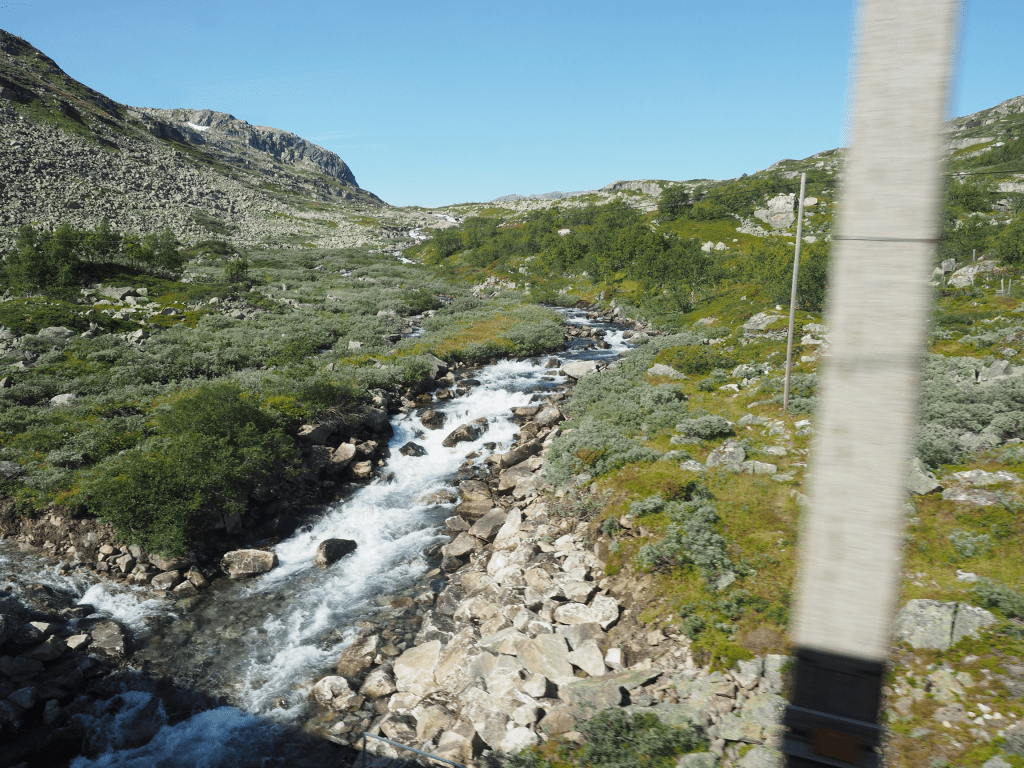

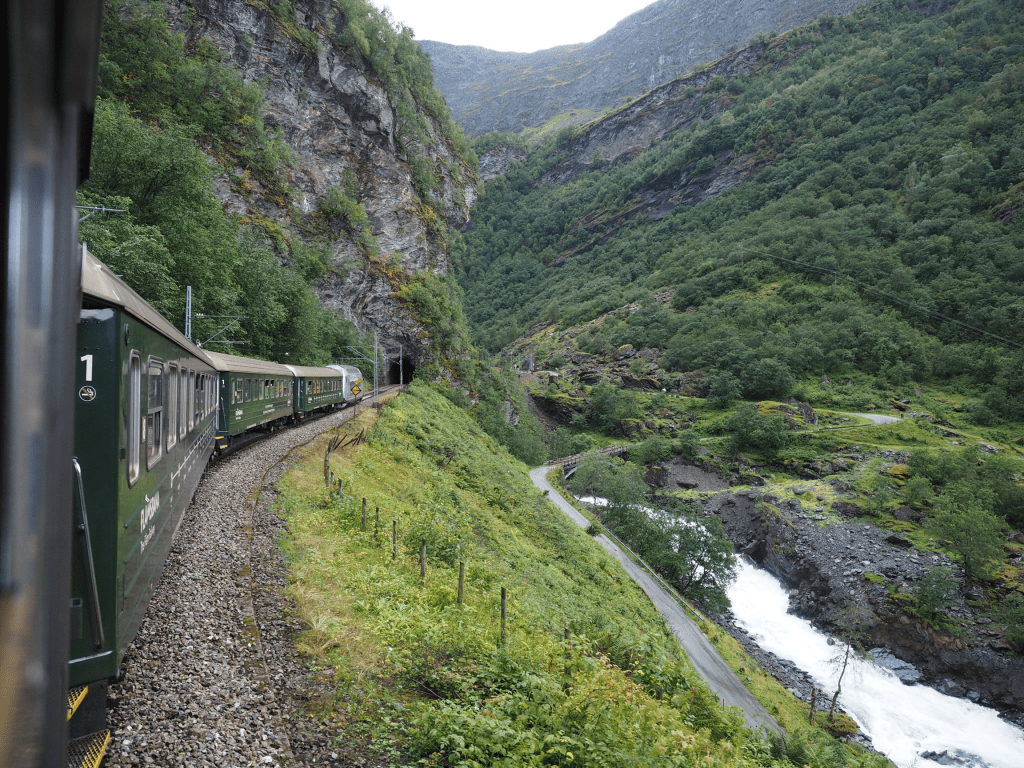

Travel general involves scenes that are expansive, whether that is natural landscapes, streetscapes or simply photographing in tight spaces. The best lenses replicating this immersive experience in photographic form is an ultra-wide-angle lens. There are many situations, especially in older cities, where an ultra-wide angle lens helps transform a simple street into a dramatic scene. This means lenses in the range of 15−20mm (10−13mm for APS-C). Some Fuji-X choices for normal and ultra-wide lenses are shown in Figure 1.

Here are some of the things to consider when choosing a lens for travel photography:

- weather-resistance − Not every day is sunny when travelling, so having some protection against moisture and dust is a good idea.

- auto-focus + manual focus − Auto-focus makes taking photography easier, especially as the window for taking a shot can be limited. It’s also nice to have some control over more artistic shots with the option of manual focus.

- a reasonable large aperture, good for low-light − Nobody wants to lug a flash around when touring, as it can be somewhat invasive.

- compact enough to fit in a pocket − For a secondary lens, it’s handy just top be able to fit it in a pocket, or small bag.

This isn’t the telephoto you’re looking for

Some will argue that a telephoto while travelling is a must-have, helping to capture scenes that are physically out of reach, I would argue the opposite. On most trips, telephoto lenses just aren’t needed. They might be great for a safari, but traipsing through the alps, or the streets of Rome, there is little need for a telephoto. There may be some shots you won’t get, particularly those in the distance, but frankly travel is about immersing yourself in the immediate surroundings. There wouldn’t be much point in taking a photo of a Roman statue from a distance.

A zoom lens for those who want a single lens

For those who prefer a single lens, then the answer might be a zoom lens. Firstly, avoid the superzoom lens – these are cover everything from wide to ultra-telephoto providing a broad range of focal lengths. These offer exceptional flexibility, but at the expense of being heavy, which can impact travel portability. In addition they often just aren’t wide enough. For example Tamron makes a 18-300mm lens for Fuji-X cameras (f/3.5-f/6.3), which covers everything really – in terms of FF this is 27-450mm. That’s a *lot* of lens. But the lens is 620g, which is heavy, well heavier than I would want to lug around everyday, and at f/3.5 it is kind-of slow. Besides which, based on the previous discussion, there is little need for a telephoto zoom when travelling.

If you only want a zoom lens, stick to one which encompasses wide, normal, and perhaps portrait – for Fuji this would be something like a 16-55mm (24-82.5mm FF), considered by some to be the “Swiss Army Knife” of lenses. Or perhaps the lighter, less expensive Sigma 18-50mm (27-75mm FF). Figure 2 shows a series of potential zooms for Fuji-X, all of which are autofocus (generally for Fuji-X, the only autofocus lenses are restricted to Fujifilm, Sigma and Tamron lenses).

Artisanal lenses

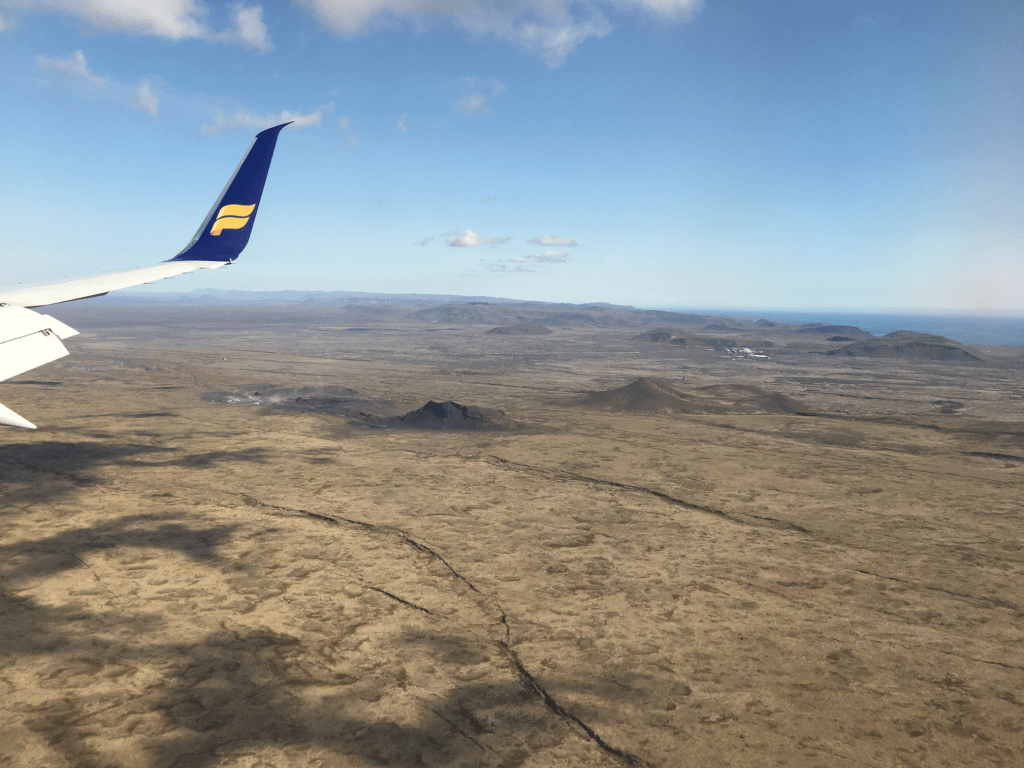

Another interesting lens to take along is a fish-eye lens, allowing for the creation of whimsical and fun travel photographs. A fish-eye is the wider alternative to the ultra-wide, and generally comes in a circular, or diagonal format. Both these formats generally exhibit some form of distortion, hence the reason they are usually used in a more artistic way. They are also perfect for photographing large, cavernous spaces, i.e. those whose grandeur would not be represented clearly by any other lens, e.g. cathedral ceilings. What about distortion? Consider it part of the art. Figure 3 shows some fish-eye choices for Fuji-X.

The final choice?

In many cases you will end up using a single lens for 80-90% of the time. What that lens is, is really up to the needs of the photographer. What if you had to choose only one lens to take long on your travels? Some people photograph an entire trip entirely using a 35mm lens (APS-C 23mm), others may choose a versatile zoom. Or perhaps the best option is to compact zoom, and a wide aperture normal, e.g. 35mm f/1.4 (APS-C). A 35mm lens (23mm APS-C) is suitable for most landscapes, and covers most aspects of daily life encountered in street photography. For example the Fujifilm 23mm f/2 R WR is compact, lightweight, and has a horizontal AOV of 55°, which is reasonable. On the downside, low-light situations aren’t fantastic, and close-up shots can be soft. But it is weather resistant, less expensive than one of Fuji’s top lenses, and is fast to focus. Everything is a compromise.

Many people will push native lenses only, e.g. Fujifilm – it’s not necessary, there are many good 3rd party lenses, the only caveat being that many are manual focus only.

N.B. Prices are in US$, and AOV’s shown in the figures are always horizontal.

Further reading:

- Alik Griffin − Fujifilm X Mount Lens List

- FujiFrame − Fujifilm Lenses

- Ahad Halari approaches his travel photos with a piscine perspective, Feroz Khan, The Phoblographer (July, 2021)