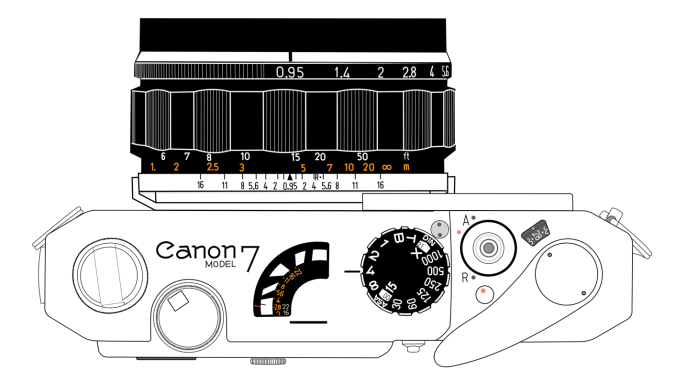

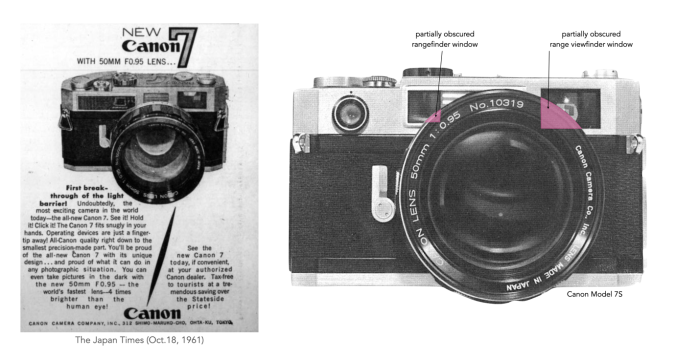

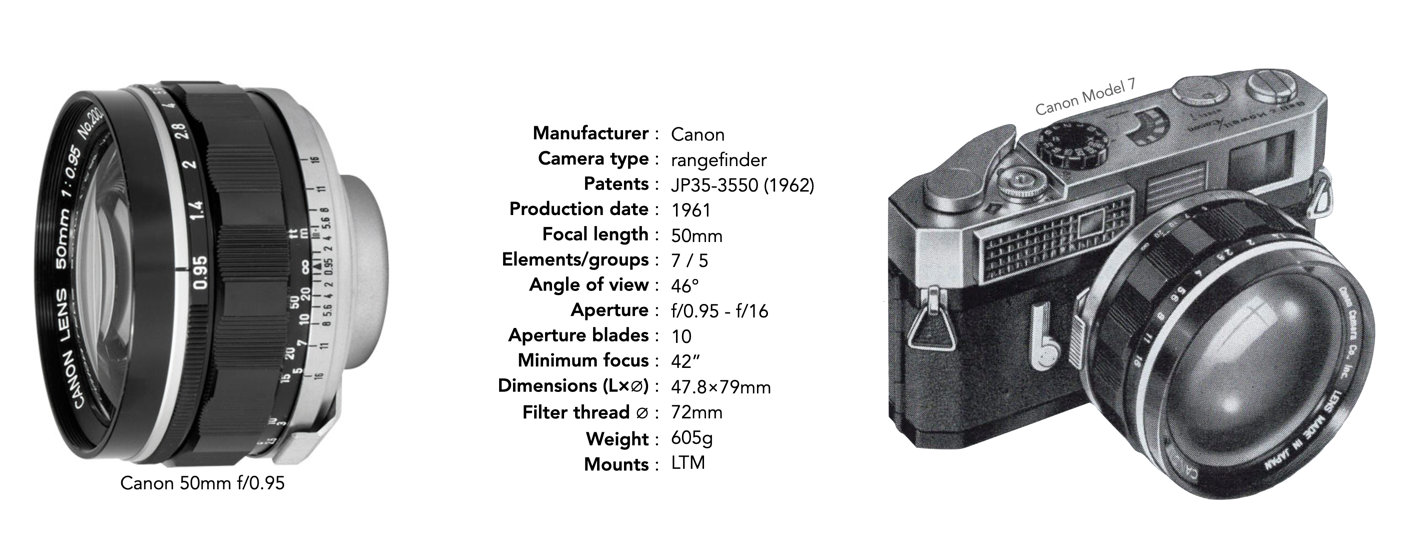

In August 1961, Canon released the 50mm f/0.95, designed as a standard lens for the Canon 7 rangefinder camera. At below f/1.0, it was the world’s fastest 35mm lens. It was created by lens designer Mukai Jirou, who also created several other rangefinder lenses for Canon (35mm f/1.5, 35mm f/1.8, 85mm f/1.8, and 100mm f/2). The Canon f/0.95 was often advertised attached to the Model 7, the first rangefinder Canon with four projected, parallax-compensating field frame lines.

It was supposedly given the name “Dream Lens”, by British photojournalists, a term soon picked up by Canon’s astute marketing department (the exact source of the term is a mystery). The advertising generally touted the fact that it was “the world’s fastest lens, four times brighter than the human eye” (how this could be measured is questionable). In addition it was advertised as giving “least-flare edge-to-edge sharpness, and is ideally corrected for aberration”. Despite the hype, there are no reviews in photographic magazines of the period beyond a quick summary paragraph of the camera.

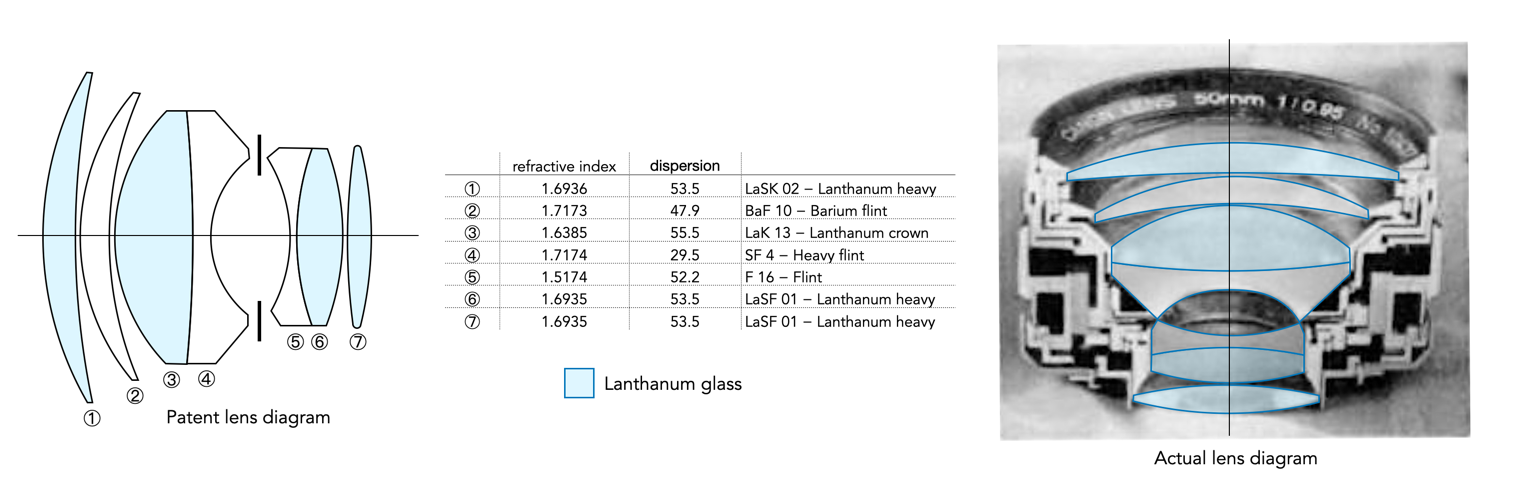

The lens incorporated rare-earth Lanthanum glass in four of the seven lens elements (there were no elements containing Thorium). However the entire lens design took some compromises. This chunky 605g, 79mm diameter lens was so large on the Canon 7 that it obscured a good part of the view in the bottom right-hand corner of the viewfinder, and partially obscured the field-of-view. However the rear lens element had to have about 10mm removed from the top to clear the interlocking roller associated with the rangefinder coupling mechanism, and a metal collar with four protruding feet had to be added to the back section to protect the rear element if the lens was placed on a flat surface with the front element facing up.

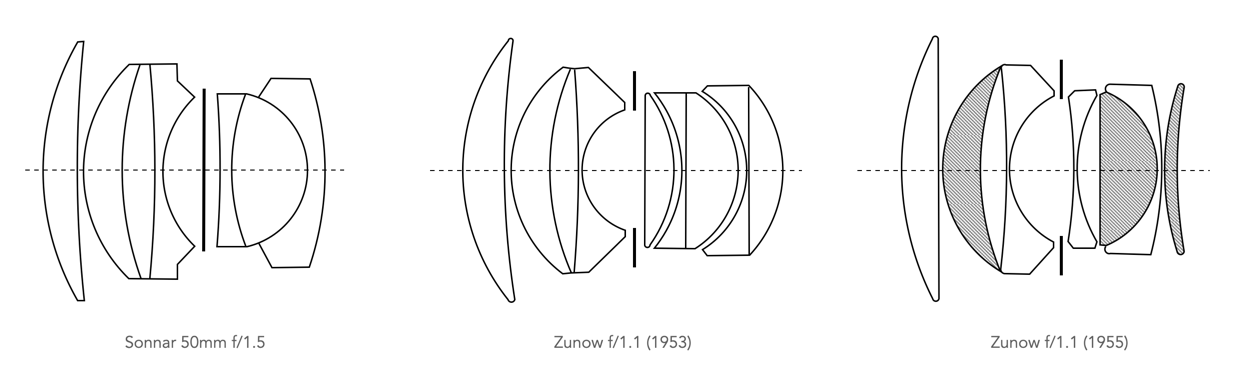

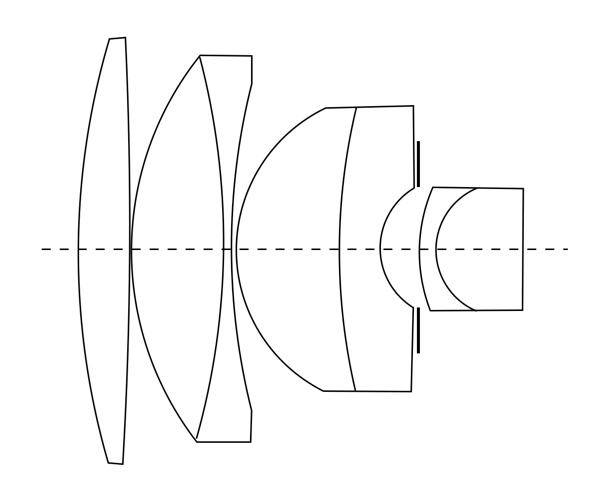

It is Gauss type lens with 7 elements in 5 groups. In it is suggested that while there are many six-element Gaussian lenses, most suffer from some degree of oblique spherical aberration, with significant flare when used at maximum aperture.

There seems to be one Japanese patent of 1962, No.35-3550, [1] that may form the basis of this lens, although the lens diagram in the patent is not the same as that portrayed for the actual lens. The lens described also appears in a U.S. patent [2] where it is specified as an f/1.2 lens. The work has its underpinnings in an earlier Japanese patent, No.205,109 (Publication No.6,685/1953 corresponding to a US patent of 1954 [3]) which showed that spherical aberration could be reduced by selecting the appropriate arrangement of the refractive indices and radii of curvature at the cemented surfaces of each element. The purpose of the design was to create a lens that produced a high quality image.

How do users view the lens today? Overall it could be described as having a lot of vignetting, spherical aberration and quite a bit of softness [7]. Some suggest the soft-focus effect contributes to the lens’ ‘ethereal quality’, and the rendering has an impressionistic quality [4]. Some suggest that it isn’t very sharp wide open [7], having a ‘razor thin depth of field’ [7]. Bokeh is described as ‘Nisen-bokeh’ [5], and a ‘very retro, swirly’ bokeh [7].

Some 20,000 copies of this rangefinder-coupled lens were produced between May 1961 and September 1970. Between 1970 and 1984, Canon continued to manufacture a version of this lens for TV cameras and cinematography which had no rangefinder coupling. Of these, about 7,000 copies were produced. When released the lens cost 57,000 yen. The average yearly salary in Japan in 1961 was ¥294,000, so this lens was the equivalent of one-fifth of a years salary. In the US the Canon 7 was sold under the guise of Bell & Howell/Canon, and in 1962, with the body and lens retailing for $499.95, and the 50mm f/0.95 lens by itself for $320, with the f/1.2 at $210. To put this into context, $320 in 1962 is worth about $3430 today, and a Canon 7 with a f/0.95 lens in average condition sells for around this value. Lenses in mint condition are valued at around C$2200-5000.

Note: The lens is also often rehoused as a cine lens by companies such as Whitehouse Optics (the cost is €6,500, not including the cost of the optics).

Further reading:

- Canon, Utility Patent Japan, “High Photography Lens”, 35-3550 (1962)

- Hiroshi Ito, US2,836,102, “High Aperture Photographic Lens”, (Jun.14, 1956)

- Hiroshi Ito, US2,681,594, “Photographic Objective of Gauss Type”, (Jun.29, 1951)

- Living with the Canon 50mm f0.95 “Dream Lens”, (Jan.30, 2023)

- Canon 50mm f0.95 – A Lens has Emotional Character, (Jul.18, 2020)

- Canon 50mm f0.95 Review, James Fox-Davies (Nov.12, 2015)

- The Canon 50/0.95 TV ‘Dream Lens’ review, Joeri (Nov.21, 2017)