Below are some more myths associated with travel.

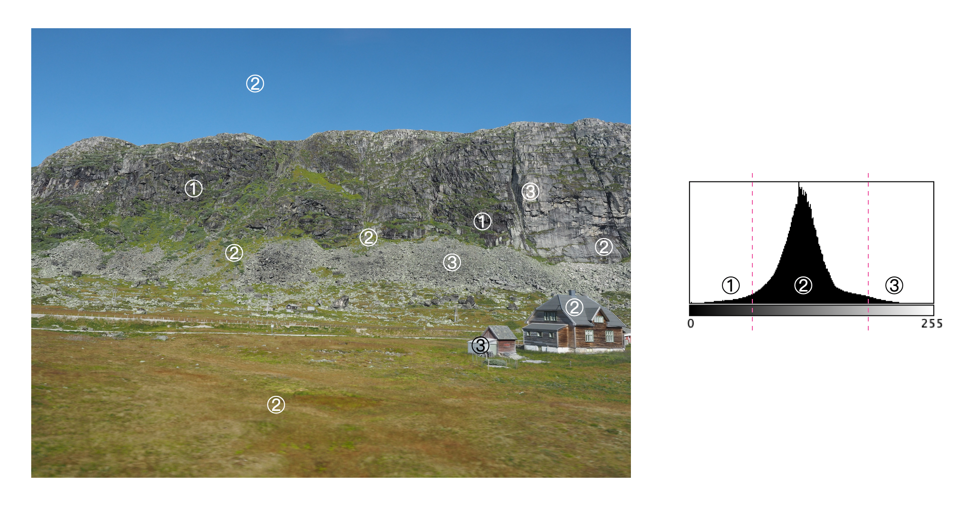

MYTH 13: Landscape photographs need good light.

REALITY: In reality there is no such thing as bad light, or bad weather, unless it is pouring. You can never guarantee what the weather will be like anywhere, and if you are travelling to places like Scotland, Iceland, or Norway the weather can change on the flip of a coin. There can be a lot of drizzle, or fog. You have to learn to make the most the situation, exploiting any kind of light.

MYTH 14: Manual exposure produces the best images.

REALITY: Many photographers use aperture-priority, or the oft-lauded P-mode. If you think something will be over- or under-exposed, then use exposure-bracketing. Modern cameras have a lot of technology to deal with taking optimal photographs, so don’t feel bad about using it.

MYTH 15: The fancy camera features are cool.

REALITY: No, they aren’t. Sure, try the built-in filters. They may be fun for a bit, but filters can always be added later. If you want to add filters, try posting to Instagram. For example, high-resolution mode is somewhat fun to play with, but it will eat battery life.

MYTH 16: One camera is enough.

REALITY: I never travel with less than two cameras, a primary, and a secondary, smaller camera, one that fits inside a jacket pocket easily (in my case a Ricoh GR III). There are risks when you are somewhere on vacation and your main camera stops working for some reason. A backup is always great to have, both for breakdowns, lack of batteries, or just for shooting in places where you don’t want to drag a bigger camera along, or would prefer a more inconspicuous photographic experience, e.g. museums, art galleries.

MYTH 17: More megapixels are better.

REALITY: I think optimally, anything from 16-26 megapixels is good. You don’t need 50MP unless you are going to print large posters, and 12MP likely is not enough these days.

MYTH 18: Shooting in RAW is the best.

REALITY: Probably, but here’s the thing, for the amateur, do you want to spend a lot of time post-processing photos? Maybe not? Setting the camera to JPEG+RAW is the best of both worlds. There is the issue of JPEG editing being destructive and RAW not.

MYTH 19: Backpacks offer the best way of carrying equipment.

REALITY: This may be true getting equipment from A to B, but schlepping a backpack loaded with equipment around every day during the summer can be brutal. No matter the type, backpacks + hot weather = a sweaty back. They also make you stand out, just as much as a FF camera with a 300mm lens. Opt instead for a camera sling, such as one from Peak Design. It has a much lower form factor and with a non-FF camera offers enough space for the camera, an extra lens, and a few batteries and memory cards. I’m usually able to shove in the secondary camera as well. They make you seem much more incognito as well.

MYTH 20: Carrying a film-camera is cumbersome.

REALITY: Film has made a resurgence, and although I might not carry one of my Exakta cameras, I might throw a half-frame camera in my pack. On a 36-roll film, this gives me 72 shots. The film camera allows me to experiment a little, but not at the expense of missing a shot.

MYTH 21: Travel photos will be as good as those in photo books.

REALITY: Sadly not. You might be able to get some good shots, but the reality is those shots in coffee-table photo books, and on TV shows are done with much more time than the average person has on location, and with the use of specialized equipment like drones. You can get some awesome imagery with drones, especially for video, because they can get perspectives that a person on the ground just can’t. If you spend an hour at a place you will have to deal with the weather that exists – someone who spends 2-3 days can wait for optimal conditions.

MYTH 22: If you wait long enough, it will be less busy.

REALITY: Some places are always busy, especially so it if is a popular landmark. The reality is short of getting up at the crack of dawn, it may be impossible to get a perfect picture. A good example is Piazza San Marco in Venice… some people get a lucky shot in after a torrential downpour, or some similar event that clears the streets, but the best time is just after sunrise, otherwise it is swamped with tourists. Try taking pictures of lesser known things instead of waiting for the perfect moment.

MYTH 23: Unwanted objects can be removed in post-processing.

REALITY: Sometimes popular places are full of tourists… like they are everywhere. In the past it was impossible to remove unwanted objects, you just had to come back at a quieter time. Now there are numerous forms of post-processing software like Cleanup-pictures that will remove things from a picture. A word of warning though, this type of software may not always work perfectly.

MYTH 24: Drones are great for photography.

REALITY: It’s true, drones make for some exceptional photographs, and video footage. You can actually produce aerial photos of scenes like the best professional photographers, from likely the best vantage points. However there are a number of caveats. Firstly, travel drones have to be a reasonable size to actually be lugged about from place to place. This may limit the size of the sensor in the camera, and also the size of the battery. Is the drone able to hover perfectly still? If not, you could end up with somewhat blurry images. Flight time on drones is usually 20-30 minutes, so extra batteries are a requirement for travel. The biggest caveat of course is where you can fly drones. For example in the UK, non-commercial drone use is permitted, however there are no-fly zones, and permission is needed to fly over World heritage sites such as Stonehenge. In Italy a license isn’t required, but drones can’t be used over beaches, towns or near airports.