I have worked on image processing algorithms on and off for nearly 30 years. I really don’t have much to show for it because in reality I found it was hard to build on algorithms that already existed. What am I talking about, don’t all techniques evolve? Well, yes and no. What I have learned over the years is that although it is possible to create unique, automated algorithms to process images, in most cases it is very hard to make those algorithms generic, i.e. apply the algorithm to all images, and get aesthetically pleasing results. And I am talking about image processing here, i.e. improving or changing the aesthetic appeal of images, not image analysis, whereby the information in an image is extracted in some manner – there are some good algorithms out there, especially in machine vision, but predominantly for tasks that involve repetition in controlled environments, such as food production/processing lines.

The number one thing to understand about the aesthetics of an image is that it is completely subjective. In fact image processing would be better termed image aesthetics, or aesthetic processing. Developing algorithms for sharpening an image is all good and well, but it has to actually make a difference to an image from the perspective of human perception. Take unsharp masking for example – it is the classic means of applying sharpening to an image. I have worked on enhanced algorithms for sharpening, involving morphological shapes that can be tailored to the detail in an image, and while they work better, for the average user, there may not be any perceivable difference. This is especially true of images obtained using modern sharp optics.

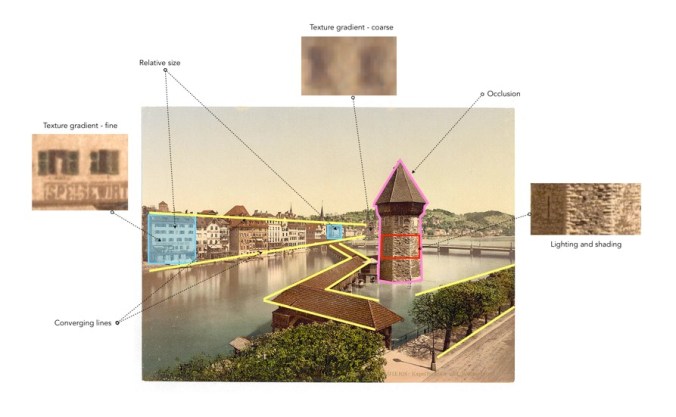

Part of the process of developing these algorithms is understanding the art of photography, and how simple things like lenses, and how various methods of taking a photo effect the outcome. If you ignore all those and just deal with the mathematical side of things, you will never develop a worthy algorithm. Or possibly you will, but it will be too complicated for a user to understand, let alone use. As for algorithms that supposedly quantify aesthetics in some manner – they will never be able to aesthetically interpret an image in the same way as a human.

Finally, improving the aesthetic appeal of an image can never be completely given over to an automated process, although the algorithms provided in many apps these days are good. Aesthetic manipulation is still a very fluid, dynamic, subjective process accomplished best through the use of tools in an app, making subtle changes until you are satisfied with the outcome. The problem with many academically-motivated algorithms is that they are driven more from a mathematical stance, rather than one based on aesthetics.