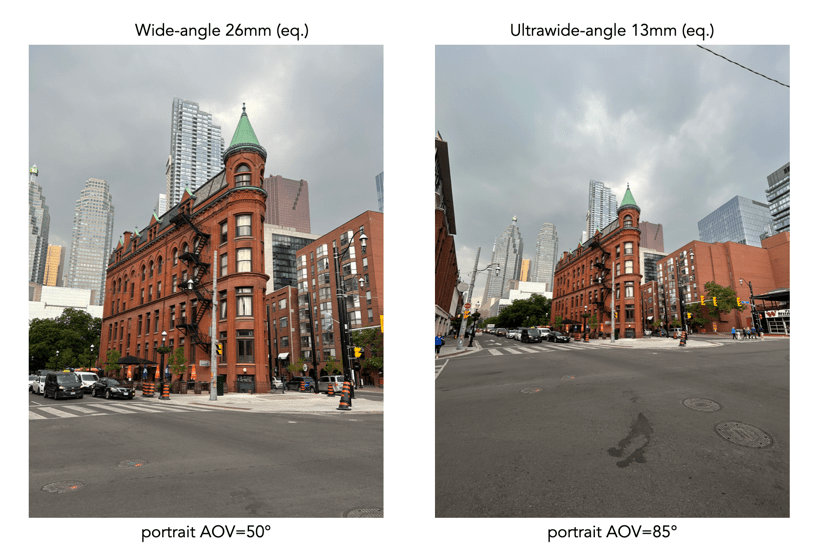

I must say, I quite like the wide lenses on the iPhone 14. It has two rear-facing cameras, an ultra-wide with a focal length of 13mm, and a 26mm wide (full-frame equiv). I don’t really want to get into reviewing these cameras, because other people have already done extensive reviews. An example of a portrait shot taken with each camera is shown below in Figure 1 (picture of the Gooderham “flatiron” Building in Toronto).

But I do want to talk briefly about the Angle of View (AOV) of these cameras. Firstly, you really have to hunt for some of this information. Apple doesn’t really talk about sensor size, or even AOV to any great extent. The most they give you is that the AOV of the ultrawide camera is 120°. But they don’t tell you the full story (maybe because most people don’t care?). It may be 120°, but only in landscape mode, and that angle describes the diagonal angle, which as I have mentioned before isn’t really that useful for most people because it is much harder to conceptualize than horizontal degrees (it’s no different to TV’s, and nobody measures a TV based on its diagonal).

| Pixel count | Focal length | Sensor size | f-number | AOV landscape | Crop factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12MP | 26mm (equiv.) | Type 1/1.7 (9.5×7.6mm) | f/1.5 | 69° (H) | 4.6 |

| 12MP | 13mm (equiv.) | Type 1/3.4 (4×3mm) | f/2.4 | 108°(H) 120°(D) | 8.6 |

So the wide-angle camera has a horizontal AOV of 69°, and the ultrawide has an AOV of 108°. But this is when a photograph is taken in landscape mode. When a photograph is taken in portrait mode, the horizontal AOV defaults to the vertical AOV from landscape mode – this means 85° for the wide, and a mere 50° for the ultrawide. This concept is the same for all sensors in all cameras, because in portrait mode the width of the photo is obviously less than that of the landscape photo. In mobile devices such as the iPhone this does become a little trickier, because most photos are likely taken in portrait mode.

Examples of the AOV’s in portrait mode for each of the focal lengths as they relate to the photographs in Figure 1 are shown below in Figure 2 (along with the potential AOV’s for landscape mode).

This is really more of a specification problem, information which I wish Apple would just post instead of ignoring. Some people are actually interested in these sort of things.