In the 1940s, a lens speed of f/3.5 was quite normal, an f/2 very fast. The world first f/1.4 lens for a 35mm camera appeared in 1950, when Nikon released the NIKKOR-S 5cm f/1.4. That sparked a series of f/1.4 lenses from most manufacturers. But this wasn’t fast enough. In the world of vintage lenses, f/1.2 lenses are almost the holy grail. Fujinon was the first to introduce an f/1.2 5cm lens in 1954 for rangefinder cameras. Canon introduced a 50mm f/1.2 lens, for the Canon S series in 1956. Many manufacturers followed suit, producing one or more lenses in the decades to come. Japanese camera companies lead the way in super-fast normal lenses. Some milestones:

- First f/1.2 lens (1954) – Fuji Fujinon 5cm f/1.2 (35mm rangefinder)

- First f/1.2 for SLR (1962) – Canon Super-Canonmatic R 58mm f/1.2

- First f/1.2 55mm lens (1965) – Nikon Nikkor-S Auto 55mm f/1.2

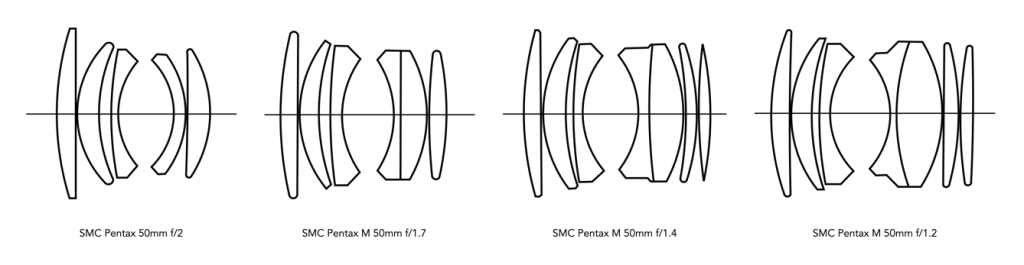

- First f/1.2 50mm lens for SLR (1975) – Pentax SMC 50mm f/1.2

Aside from the fact that these f/1.2 lenses represent the pinnacle of wide-open lenses of the period, what makes them so expensive (both then and now)?

- Rarity – Although a large number of manufacturers developed f/1.2 lenses, in may cases fewer were manufactured than slower lenses. For example, the Fujinon 5cm f/1.2 lens was made in limited amounts, less than 1000 by all accounts, but because of this ranges from $4000-20000.

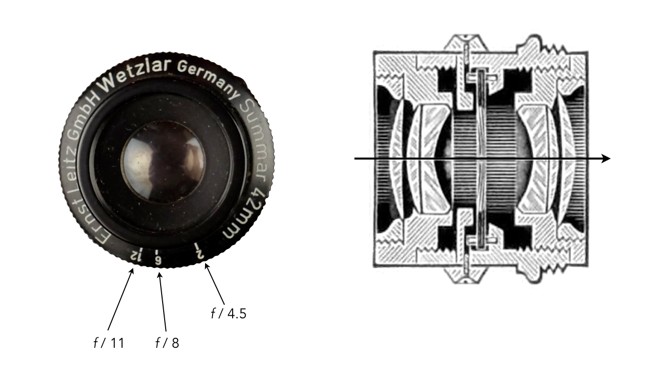

- Larger glass – As the speed of a lens increased, so too did the size of its optical elements. An f/1.2 lens had much more glass than say an f/2.8, e.g. a 50mm f/2.8 lens would have an effective aperture of 25mm, while an f/1.2 50mm would have one of 41.7mm. This means the optical elements had to be much larger for an f/1.2 lens.

- Better glass – Larger optical elements also mean they had to be of a higher quality, with less tolerance for defects such as bubbles. Some optical elements may have been made of rare-earth metals to improve optical qualities, and reduce aberrations.

- More optical elements – As lenses got faster, more elements needed to be added to counter optical aberrations.

- Inner mechanisms – Larger optical elements meant one of two things for the lens housing (i.e. barrel): (i) make it a lot larger, and therefore increase the size of all the components, or (ii) make it marginally larger, and reduce the size of the mechanisms within the lens, e.g. aperture control, so they become more compact.

- Complex manufacturing – Specialized glass needed new processes to ensure high manufacturing tolerances, e.g. finer levels of polishing.

All these elements contributed to an increase in the cost of these “revolutionary” lenses. However, although we consider them expensive now, f/1.2 lenses were always expensive. In 1957, the Canon 50mm f/1.2 rangefinder lens sold for US$250, with the Fujinon 50mm f/1.2 at $299.50 [1]. The Canon 50mm f/1.8 on the other hand sold for $125, and a Canon V with a 50mm f/1.8 lens sold for $325. A 1970 Canon price [2] list provides a better perspective, with information for the lenses for the Canon 7/7s rangefinder. The slower 50mm lens sold for $55 (f/2.8), and $120 (f/1.8), while the f/1.4 sold for $160 and the f/1.2 for $220 (the f/0.95 was the most expensive at $320). SLR lenses were cheaper, although Canon did not make a 50mm f/1.2 (until 1980), it did make a 55mm f/1.2, which sold for $165.

Note that $220 in 2022 dollars is $1608. Today, some of these lenses fetch a good price, depending on condition. The Canon 50mm f/1.2 sells for around $400-600 based on condition. The series of f/1.2 lenses made by Tomioka Kogaku circa 1970 regularly sell for between C$800-1700.

The price of nostalgia.

Further reading:

- “Photographic Lenses”, Popular Photography 40(4), April, p.168 (1957)

- Canon Systems Equipment, Bell & Howell Co. March 1970