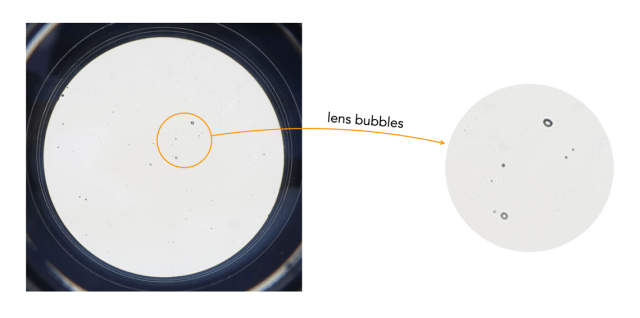

Vintage lenses of a certain era often contain air bubbles, but this by no means suggests that they are of inferior quality. A 1940 article in Minicam Photography describes this as a fallacy [1]. It seems that in early cameras, some photographers may have been weary of such imperfections. In all likelihood there are like-minded individuals today.

“They may look like undesirable blemishes, but they are much more apparent visually than photographically.” [1]

In early glass manufacturing, air bubbles were practically impossible to eliminate. At the time the rationale provided was that bubbles formed when ingredients were melted together at temperatures of 2750°F to form glass. Even first-glass lenses contained some number of bubbles.

“In the manufacture of the famous Jena glass the various elements used must be heated for a given length of time and to a certain degree, the process being stopped at just the right moment whether all the air has been driven out or not. There is no alternative.” [2]

The article goes on to provide an example of a 6-inch, f/4.5 lens with a diameter of 32mm across the front lens [1]. They count 12 bubbles, on average 0.1mm in diameter. The lens has an area of 804mm², and the bubbles an area of 0.0942mm², making up 0.012% of the surface area. So only 0.012% of the light passing through the lens is impeded by the air bubbles. The outcome? Light interference caused by bubbles is negligible.

“The actual loss of light is inappreciable, and the presence of these bubbles, even if near the surface, has no effect whatever on the optical quality of the image.” [2]

“Air bubbles will be found in most high-class lenses and are a sign of quality rather than a defect, since at present it is impossible to make certain optical glasses absolutely bubble-free; their presence doesn’t affect the quality of the image in any way. [3]

In the literature for many modern optical glass manufacturers, e.g. Schott, there are caveats on bubbles (and inclusions). Basically bubbles in glass cannot be avoided due to complicated glass compositions and manufacturing processes. The melting of raw materials produces reactions which invariably form gas bubbles in the melt (typically carbonates or hydrogen-carbonates) [4]. These bubbles are removed in the refining process, when the temperature of the glass is increased, reducing the viscosity of the glass and allowing bubbles to move up through the melt and disappear. Some residual bubbles are still left from imperfect refining. However, it is actually quite rare to see bubbles in modern lenses.

So do they make a difference in vintage glass? According to much of the literature, not at all. Besides, vintage lenses are all about character – nobody is looking for a perfect image.

Further reading:

- “Fallacy: That “air” bubbles in a lens are a sign of inferior quality”, Minicam Photography, 3(8), pp.30-31 (1940)

- “The Crucible – Air-Bubbles in Lenses”, Photo-Era, 31(6) p.319 (1913)

- “Andreas Feininger on Lenses at Work”, Popular Photography, 18(3) p.124 (1946)

- TIE-28: Bubbles and Inclusions in Optical Glass, Schott Technical Information (2016)

- “The Impact of Air Bubbles in the Optics of Old Lenses”, Jordi Fradera (2020)