Photographing large objects in the landscape can be tricky. Some are near impossible, for example bridges. An exceptional example is the Landwasser Viaduct, part of the Rhaetian Railway in Graubünden, Switzerland. The best possible shot is taken from the valley beneath, preferably with a train crossing the viaduct, but that’s not a shot possible for everybody, because most people are on the train, and therefore won’t get anywhere near the perspective of a ground shot. It’s the same with many of these famous bridges, and viaducts. Some, like the Glenfinnan Viaduct, often known as “The Harry Potter Bridge“, are easier to photograph (there are some good instructions to help find the most optimal spots). Not to say that the Landwasser Viaduct can’t be photographed, there are also good commentaries on doing that as well.

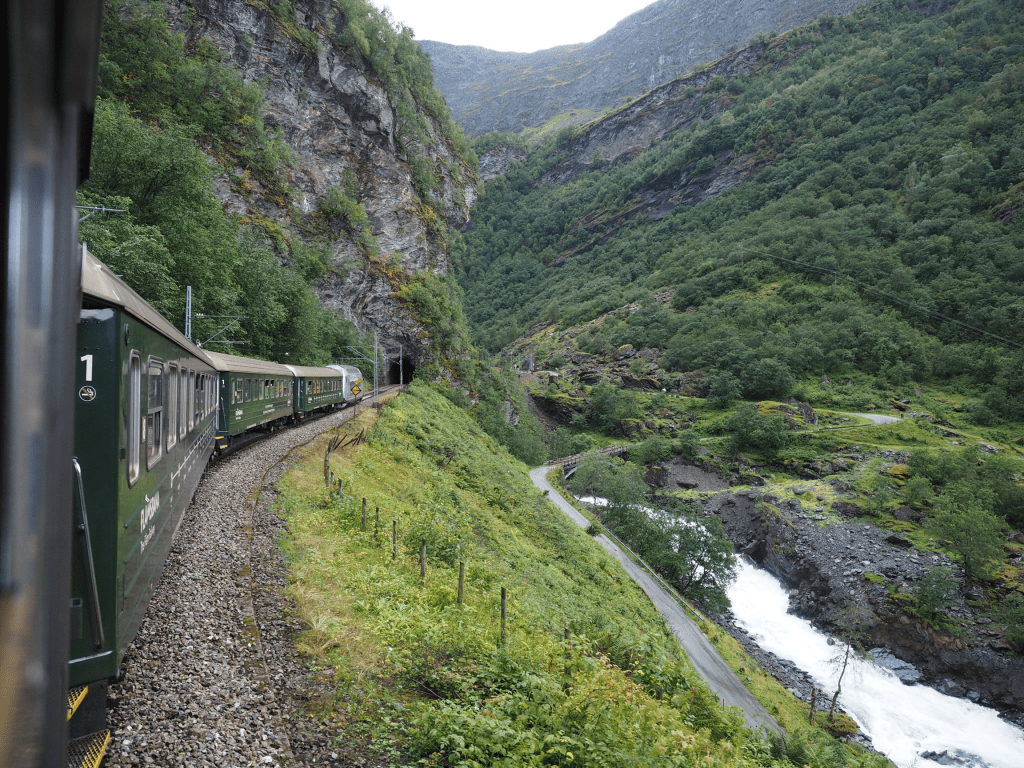

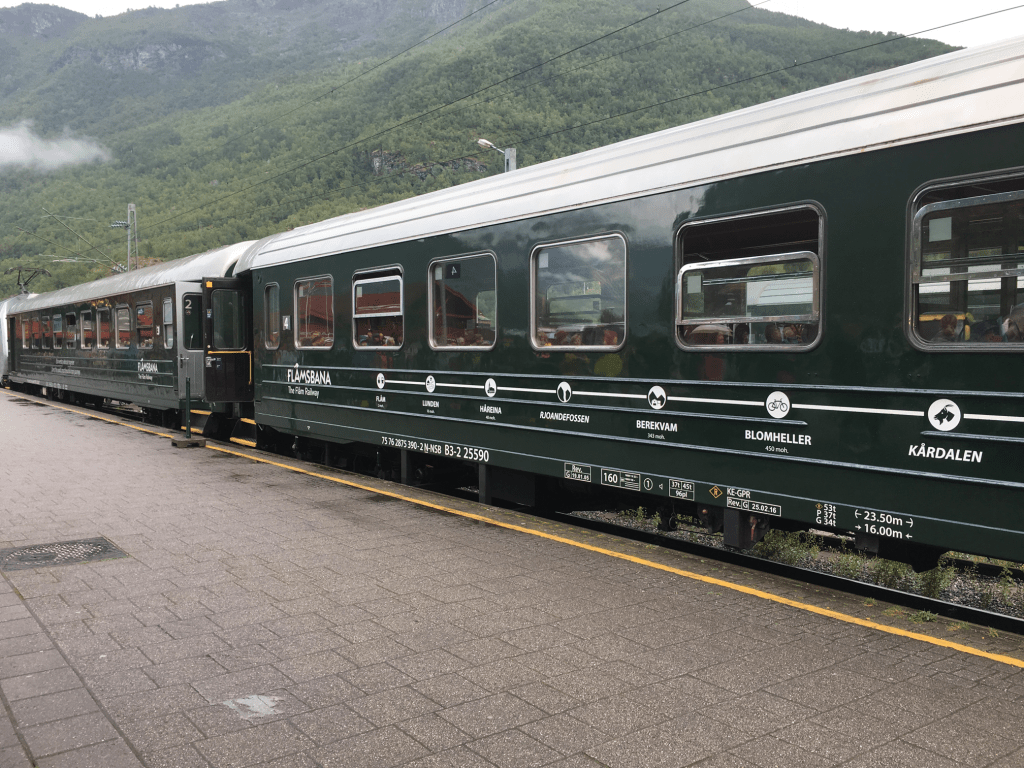

While train journeys are fun, actually photographing things from the train doesn’t always produce the images people expect. It’s the same with large objects of any sort. Sometimes the best images these days are taken using drones, because they are able to take in the whole landscape. But not everyone has a drone available, and in some places they have actually cracked down on them over the past few years. landscape scenes in Iceland are monumental when taken from a drone… these are perspectives of features like waterfalls that just can’t be achieved any other way. But at nearly every major tourist site in Iceland, you will see ‘No Drone’ signs, e.g. Gullfoss waterfall.

So if you are interested in photographing a large natural, or man-made object, what’s the best approach? There are two good methods. Firstly, shooting from a distance, to provide an overall outlook. This involves finding the best position that allows for an uninterrupted view, and makes an interesting shot. Secondly, shooting up-close, providing a near perspective of the object, photographing just a portion of the structure and bringing things like texture and intricate detailing into play. Describing an object visually should never be just a one-perspective deal. It should incorporate different granularity of details, which help describe the object as a whole. You also want to be cognizant that you don’t just create the same picture that the masses do.

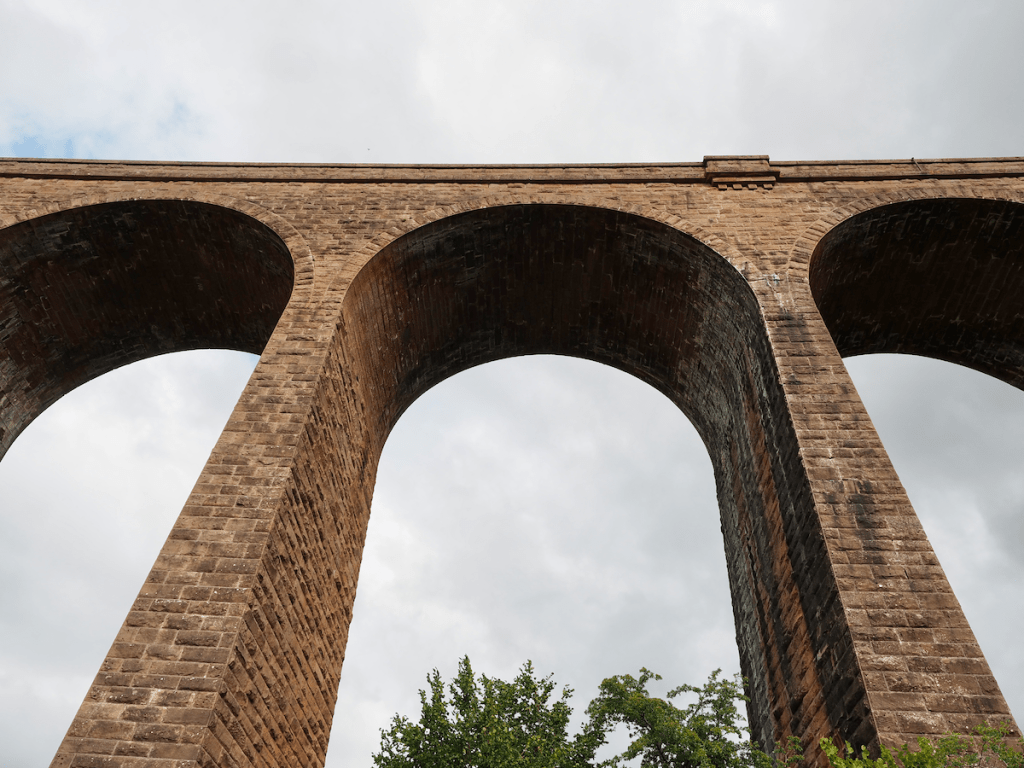

As a case in point, consider these photographs of Culloden Viaduct, just east of Inverness, Scotland. This is an easy viaduct to get both a distant shot, and close shots, as a road goes directly underneath the southern portion of the viaduct. There are many options here, shooting it from the distance to provide an overall viewpoint of the viaduct, or from one end to provide a perspective. The viaduct is a long linear feature, which means distance shots make it appear small in relation to the rest of the photograph. The photograph also feels “flat”, something that can be partially fixed by shooting from an elevated position (which is above the feature being photographed, and hence the value of drone-based photography). A perspective view will often allow the scale of the structure to be included, in addition to a more 3D feel.

Close-up shots will fail to show the viaduct in its entirety, but will instead portray more architectural details, in this case, the design of the arches. It also provides more of a three-dimensional perspective of the viaduct than long-distance shots. it is the arches that make this viaduct interesting, and a distance shot will not do them justice. A close-up view exposes the tapered structure of the piers, and the precise nature of the arches. You can even goes as far as taking shots of individual components of an object to illustrate things like texture, and interplay of materials.

P.S. Naturally, aerial shots acquire with a drone do provide much more of a perspective of an object in the context of its surroundings, but that isn’t always realistic for the average photographer.