If you don’t want to learn a programming language, but you do want to go beyond the likes of Photoshop and GIMP, then you should consider ImageMagick, and the use of scripts. ImageMagick is used to create, compose, edit and convert images. It can deal with over 200 image formats, and allows processing on the command-line.

1. Using the command line

Most systems like MacOS and Linux, provide what is known as a “shell”. For example in OSX it can be accessed through the “Terminal” app, although it is nicer to use an app like iTerm2. When a window is opened up in the Terminal (or iTerm2), the system applies a shell, which is essentially an environment that you can work in. In a Mac’s OSX, this is usually the “Z” shell, or zsh for short. It let’s you list files, change folders (directories), and manipulate files, among many other things. At this lower level of the system, aptly known as the command-line, programs can be executed using the keyboard. The command-line is different from using an app. It is not WYSIWYG, What-You-See-Is-What-You-Get, but it is perfect for tasks where you know what you want done, or you want to process a whole series of images in the same way.

2. Processing on the command line

Processing on the command-line is very much a text-based endeavour. No one is going to apply a curve-tool to an image in this manner because there is no way of seeing the process happen live. But for other tasks, things are just done way easier on the command line. A case in point is batch-processing. For example say we have a folder of 16 megapixel images, which we want to reduce in size for use on the web. It is uber tedious to have to open them up in an application, and then save each individually at a reduced size. Consider the following example which reduces the size of an image by 50%, i.e. its dimensions are reduced by 50%, using one of the ImageMagick commands:

magick yorkshire.png -resize 50% yorkshire50p.png

There is also a plethora of ready-made scripts out there, for example Fred’s ImageMagick Scripts.

3. Scripting

Command-line processing can be made more powerful using a scripting language. Now it is possible to do batch processing in ImageMagick using mogrify. For example to reduce all PNG images by 40% is simple:

magick mogrify -resize 40% *.png

The one problem here is that mogrify will overwrite the existing images, so it should be run on copies of the original images. An easier way is to learn about shell scripts, which are small programs designed to run in the shell – basically they are just a list of commands to be performed. These scripts use some of the same constructs as normal programming languages to perform tasks, but also allow the use of a myriad of programs from the system. For example, below is a shell script written in bash (a type of shell), and using the convert command from ImageMagick to convert all the JPG files to PNG.

#!/bin/bash

for img in *.jpg

do

filename=$(basename "$img")

extension="${filename##*.}"

filename="${filename%.*}"

echo $filename

convert "$img" "$filename.png"

done

It uses a loop to process each of the JPG files, without affecting the original files. There is some fancy stuff going on before we call convert, but all that does is split the filename and its extension (jpg), keeping the filename, and ditching the extension, so that a new extension (png) can be added to the processed image file.

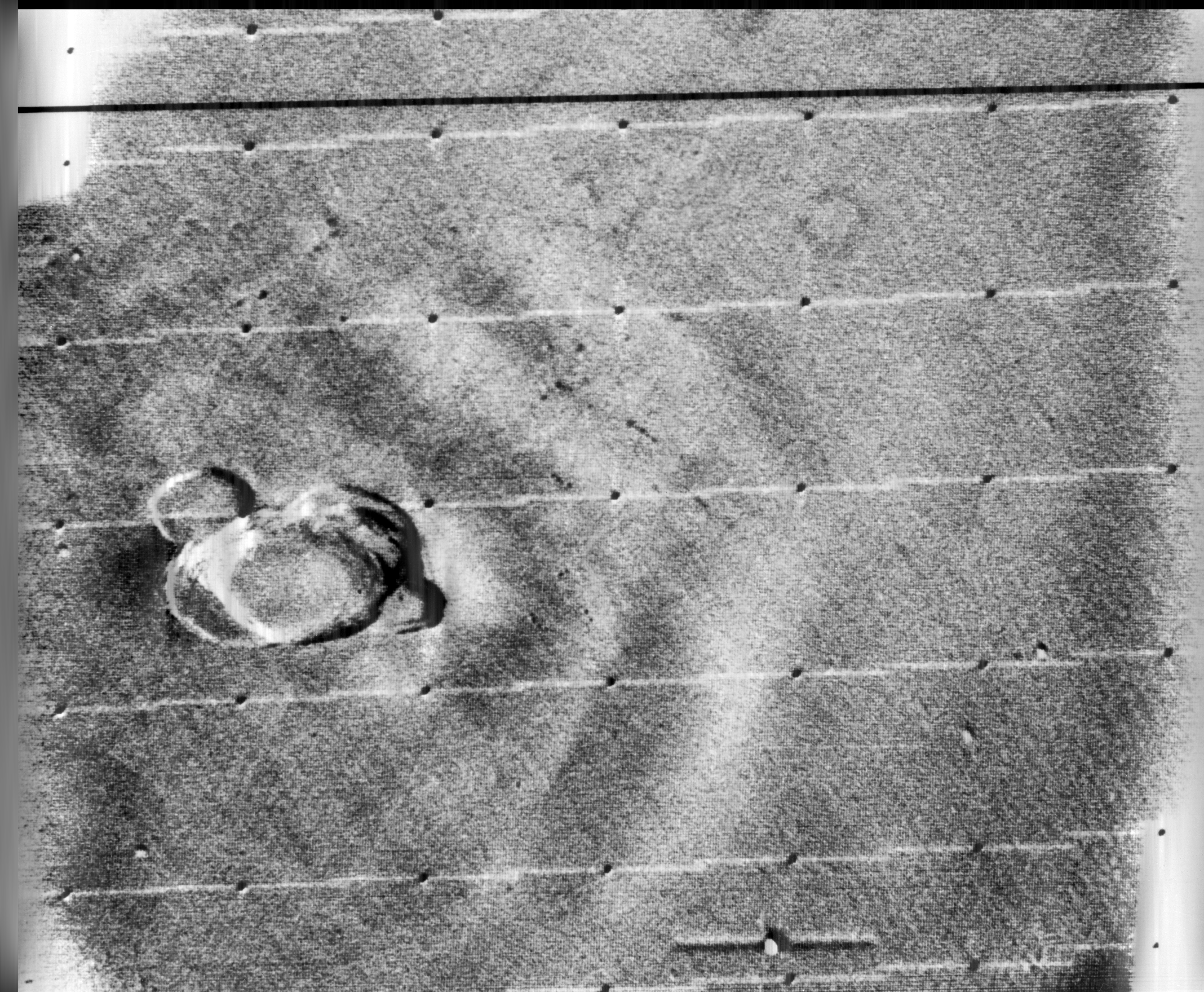

Sometimes I like to view the intensity histograms of a folder of images but don’t want to have to view them all in an app. Is there an easier way? Again we can write a script.

#!/bin/bash

var1="grayH"

for img in *.png

do

# Extract basename, ditching extension

filename=$(basename "$img")

extension="${filename##*.}"

filename="${filename%.*}"

echo $filename

# Create new filenames

grayhist="$filename$var1"

# Generate intensity / grayscale histograms

convert $filename.png -colorspace Gray -define histogram:unique-colors=false histogram:$grayhist.png

done

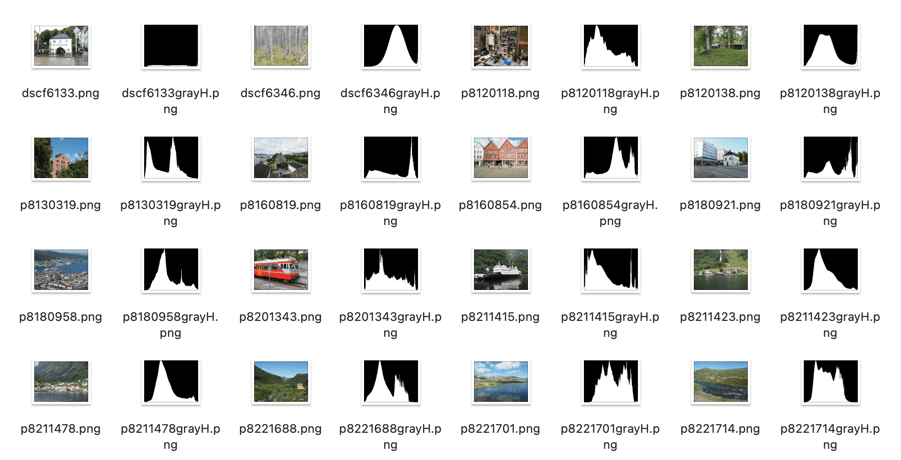

Below is a sample of the output applied to a folder. Now I can easily see what the intensity histogram associated with each image looks like.

Yes, some of these seem a bit complicated, but once you have a script it can be easily modified to perform other batch processing tasks.