A “slide” in the more common use of the word refers to a translucent positive image which is held inside a cardboard sleeve, or plastic frame (or mount). A positive image is created using reversal film, whereas negative film produces an inverted or reversed image (which in turn is used to make a paper photo). When a slide is held up to the light, it is possible to see the scene as it was shot rather than the “negative” of the scene. Slides are typically viewed using a slide projector which projects the image against a white screen. Without the mount, the film would not be able to “slide” from one image to another when inside the magazine of a projector.

The slide is not a modern phenomena. The earliest was likely the Lantern slide, also known as the “magic lantern”. It was an early type of image projector which appeared in the 17th century which projected glass slides onto various surfaces. With the advent of photographic processes in the mid-19th century, magic lantern slides were black-and-white positive images, created with the wet collodion or a dry gelatine process on glass. Slide shows became a popular pastime in the Victorian period, but they were not the same as modern film slides.

It 1826 Nicéphore Niépce invented the first form of negative photography, but it would take nearly a century before its use in flexible celluloid film became a reality. The earliest commercially successful reversal process came into being in 1907 with the Lumière Autochrome. It was an additive screen-plate method using a panchromatic emulsion on a thin glass plate coated with a layer of dyed potato starch grains. It was Leopold Godowsky Jr., and Leopold Mannes working with Kodak Research Laboratories who in April 1935 produced the first commercially successful reversal film – Kodachrome (first as a 16mm movie film, and in May 1936 as 8mm, 135 and 828 film formats). Based on the subtractive method, the Kodachrome films contained no colour dye couplers, these were added during processing. In 1936 Agfa introduced Agfa Neu, which had the dye couplers integrated into the emulsion, making processing somewhat easier than Kodachrome.

For sparkling pictures big as life. . . . Kodak 35 mm color slides.

Kodak’s commercial slogan during the 1950s

There are different types of reversal film, based on the type of processing. The first, which includes films like Kodachrome, uses the K-14 process. Kodachrome is essentially a B&W stock film, with the colour added during the 14-step development process. That means it has no integrated colour couplers. Kodachrome was an incredible film from the perspective of the richness and vibrancy of the colours it produced – from muted greens and blues to bold reds and yellows. However developing Kodachrome was both complex and expensive, which would eventually see the rise of films like Ektachrome, which used the E-6 development process (a 6-step process). Films like Ektachome have different emulsion layers, each of which is sensitive to a different colour of light. There are also chemicals called dye couplers present in the film. After slide film is developed, the image that results from the interaction of the emulsion with the developer is positive.

Many companies made reversal films, typically acknowledged through the use of the “chrome” synonym – e.g. Agfachrome (Agfa), Fujichrome (Fuji), Ektachrome (Kodak), Scotchchrome (3M, after buying Italian filmmaker Ferrania), Ilfochrome (Ilford), Peruchrome (Perutz), and Anscochrome (the US arm of Agfa). The initial Kodachrome had a very slow speed (10 ASA), this was replaced in 1961 by Kodachrome II (1961) which produced sharper images, and had a faster speed (25 ASA). In 1962 Kodak introduced Kodachrome X (ASA 64). Kodak’s other transparency film was Ektachrome, which was much faster than Kodachrome. In 1959 High Speed Ektachrome was introduced, providing a ASA 160 colour film (by 1968 this had been pushed to ASA 400).

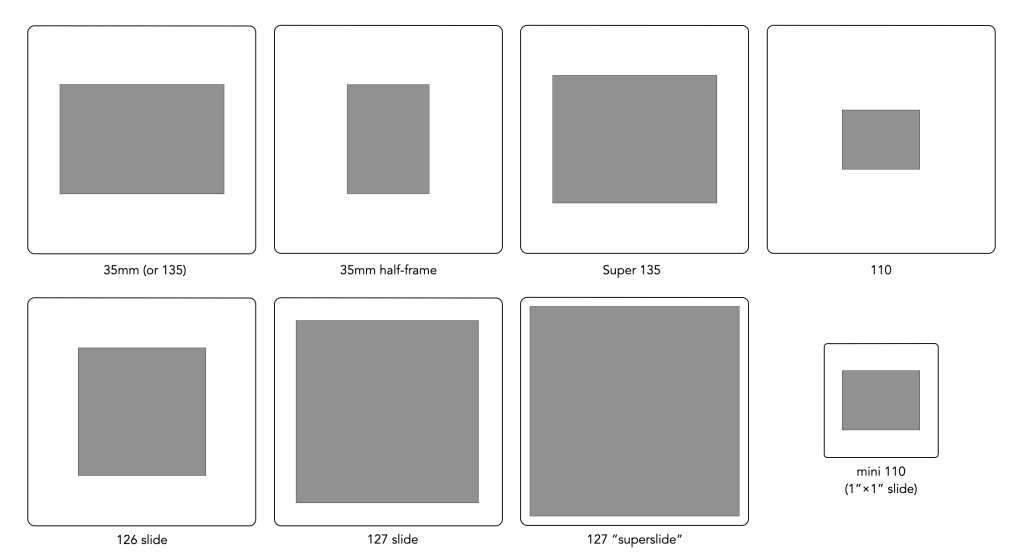

| Format | Year it appeared | Transparency size (w×h) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 35mm /135 | 1935 | 36mm × 24mm | very common |

| Super 135 | 36mm × 28mm | ||

| 110 | 1972 | 17mm × 13mm | also on 1”×1” slides (mini 110) |

| Half-frame | 1950s | 24mm × 18mm | |

| 126 | 1963 | 28mm × 28mm | |

| 127 | 1912-1995 | 40mm × 40mm | |

| Super 127 | 1912-1995 | rare |

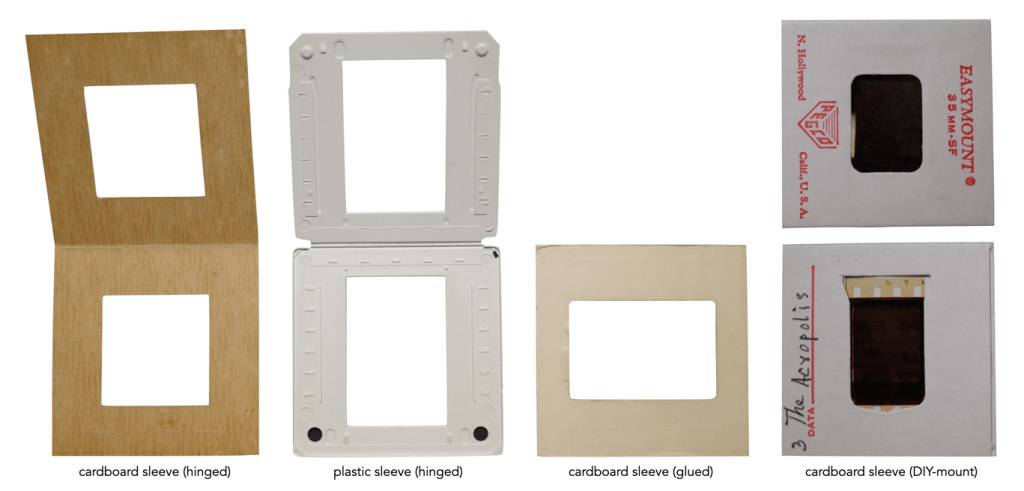

What about the “slide” side of things? A patent for a “Transparency Mount” was submitted by Henry C. Staehle of Eastman Kodak in October 1938, and received it in December 1939. Its was described as “a pair of overlapping flaps formed from a single strip of sheet material such, for example, as paper.”. Early slide mounts were mostly made of cardboard, but as plastic became more common, various designs appeared. Most cardboard mounts were either hinged on one side or two separate pieces, glued together after the emulsion was sandwiched between the two sides of the frame. There were also systems for the DIYer, where the emulsion could simply be inserted to the slide frame. Plastic frames were either welded together or designed in an adjustable format, i.e. the film frame could be inserted and removed. The exterior dimension of most common slide formats is 2 inches by 2 inches. There were many different sizes of slides, all on a standard 2″×2″ mount, to encompass the myriad of differing films formats during the period. Slides are usually colour – interestingly, black-and-white reversal film does exist but is relatively uncommon.

Slides were popular from the 1960’s probably up until the early 1990’s. It was an easy way to get a high-quality projected image in a pre-digital era. Slides were a popular medium for tourists to take pictures with, and then beguile visitors with a carousel of slides depicting tales of their travels. Slide film is still available today, all of which uses the E-6 process. E-6 slide film is a lot less forgiving as it has a lower ISO value but produces vivid colour with evidence of finer grain. Modern slide films include Kodak Ektachrome 100, Fujifilm Velvia 50, and Fujifilm Fujichrome Provia 100.

Further reading:

- Photographic Memorabilia (about films and processing)

- Timeline of Historical Film Colors