“Photographers — idiots, of which there are so many — say, ‘Oh, if only I had a Nikon or a Leica, I could make great photographs.”’ That’s the dumbest thing I ever heard in my life. It’s nothing but a matter of seeing, and thinking, and interest. That’s what makes a good photograph.”

Andreas Feininger in an interview with American Society of Media Photography (1990)

film photography

The photography of Daidō Moriyama

Daidō Moriyama was born in Ikeda, Osaka, Japan in 1938, and came to photography in the late 1950s. Moriyama studied photography under Takeji Iwamiya before moving to Tokyo in 1961 to work as an assistant to Eikoh Hosoe. In his early 20’s he bought a Canon 4SB and started photographing on the streets on Osaka. Moriyama was the quintessential street photographer focused on the snapshot. Moriyama likened snapshot photography to a cast net – “Your desire compels you to throw it out. You throw the net out, and snag whatever happens to come back – it’s like an ‘accidental moment’” [1]. Moriyama’s advice on street photography was literally “Get outside. It’s all about getting out and walking.” [1]

In the late 1960s Japan was characterized by street demonstrations protesting the Vietnam War and the continuing presence of the US in Japan. Moriyama joined a group of photographers, associated with the short-lived (3-issue) magazine Provoke (1968-69), which really dealt with elements of experimental photography. His most provocative work during the Provoke-era was the are-bure-boke style that illustrates a blazing immediacy. His photographic style is characterized by snapshots which are gritty, grainy black and white, out-of-focus, extreme contrast, Chiaroscuro (dark, harsh spotlighting, mysterious backgrounds). Moriyama is “drawn to black and white because monochrome has stronger elements of abstraction or symbolism, colour is something more vulgar…”.

“My approach is very simple — there is no artistry, I just shoot freely. For example, most of my snapshots I take from a moving car, or while running, without a finder, and in those instances I am taking the pictures more with my body than my eye… My photos are often out of focus, rough, streaky, warped etc. But if you think about I, a normal human being will in one day receive an infinite number of images, and some are focused upon, other are barely seen out of the corners of one’s eye.”

Moriyama is an interesting photographer, because he does not focus on the camera (or its make), instead shoots with anything, a camera is just a tool. He photographs mostly with compact cameras, because with street photography large cameras tend to make people feel uncomfortable. There were a number of cameras which followed the Canon 4SB, including a Nikon S2 with a 25/4, Rolleiflex, Minolta Autocord, Pentax Spotmatic, Minolta SR-2, Minolta SR-T 101 and Olympus Pen W. One of Moriyama’s favourite film camera’s was the Ricoh GR series, using a Ricoh GR1 with a fixed 28mm lens (which appeared in 1996) and sometimes a Ricoh GR21 for a wider field of view (21mm). Recently he was photographing with a Ricoh GR III.

“I’ve always said it doesn’t matter what kind of camera you’re using – a toy camera, a polaroid camera, or whatever – just as long as it does what a camera has to do. So what makes digital cameras any different?”

Yet Moriyama’s photos are made in the post-processing stage. He captures the snapshot on the street and then makes the photo in the darkroom (or in Silver Efex with digital). Post-processing usually involves pushing the blacks and whites, increasing contrast and adding grain. In his modern work it seems as though Moriyama photographs in colour, and converts to B&W in post-processing (see video below). It is no wonder that Moriyama is considered by some to be the godfather of street photography, saying himself that he is “addicted to cities“.

“[My] photos are often out of focus, rough, streaky, warped, etc. But if you think about it, a normal human being will in one day perceive an infinite number of images, and some of them are focused upon, others are barely seen out of the corner of one’s eye.”

For those interested, there are a number of short videos. The one below shows Moriyama in his studio and takes a walk around the atmospheric Shinjuku neighbourhood, his home from home in Tokyo. There is also a longer documentary called Daidō Moriyama: Near Equal, and one which showcases some of his photographs, Daido Moriyama – Godfather of Japanese Street Photography.

Further Reading:

- Nakamoto, T., Moriyama, D., “Daido Moriyama How I Take Photographs”, (2019)

- Eric Kim, 5 Lessons Daido Moriyama Has Taught Me About Street Photography

Does a lack of colour make it harder to extract the true context of pictures?

For many decades, achromatic black-and-white (B&W) photographs were accepted as the standard photographic representation of reality. That is until the realization of colour photography for the masses. Kodak introduced Kodachrome in 1936 and Ektachrome in the 1940s which lead to the gradual, popular adoption of colour photography. It only became practical for everyday photographers during the mid-1950s after film manufacturers had invented processes that made colour pictures sufficiently easy to develop. That didn’t mean that B&W disappeared from society, as in certain fields like journalistic photography they remained the norm. There were a number of reasons for this – news photos were generally printed in B&W, and B&W film was faster, meaning less light was needed to take an image, allowing photojournalists to shoot in a variety of conditions. So from a journalistic viewpoint, people interpreted the news of the world in B&W for nearly a century.

The difference between B&W and colour is that humans don’t see the world in monochromatic terms. Humans have the potential to discern millions of colours, and yet are limited to approximately 32 shades of gray. We have evolved in this manner because the world around us is not monochromatic, and our very survival once depended on our ability to separate good food from the not so good. Many things can be inferred from colour. Many things are lost in B&W. Colour catches the eye, and highlights regions of interest. For instance, setting and time of day/year can be inferred from a photograph’s colours. Mood can also be communicated based on colour.

Black-and-white photographs offer a translation of our view of the world into a unique achromatic medium. Shooting B&W photographs is clearly more challenging because unlike the 16 million odd colours available to describe a scene, B&W typically offers only 256, from pure black (0), to pure white (255). Take for example a photograph taken during the First World War. These photographs were typically B&W, and grainy, painting a rather grim picture of all aspects of society during this period. We typically associated B&W with nostalgia. There was some colour photography during the early 20th century, provided by the Autochrome Lumière technology, and resulting in some 72,000 photographs of the time period from places all over the world. But seeing things in B&W means having to interpret a scene without the advantage of colour. Consider the following photograph from Paris during the early 1900s. It offers a very vibrant rendition of the street scene, with the eye drawn to the varied colour posters on the wall of the building.

Without the colour, we are left with a somewhat drab and gloomy scene, befitting the somber mood associated with the early years of the early 20th century. In the B&W we cannot see the colour of the posters festooning the buildings. What is interesting is that we are likely not use to seeing colour photographs from before the 1950s. It’s almost like we expect images from the before 1950 to be monochromatic, maybe because we perceive these years filled with hardship and suffering. But there is something unique about the monochrome domain.

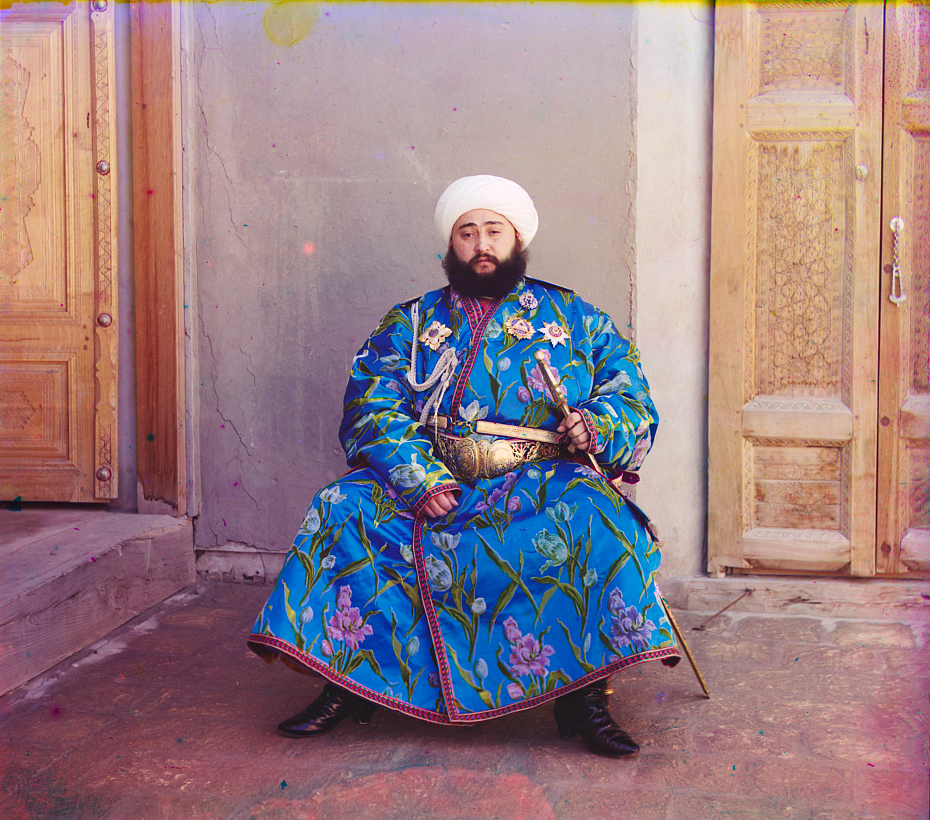

The aesthetic of black-and-white photographs is based on many factors, including lighting, any colour filters that were used during acquisition of the photograph, and the colour sensitivity of the B&W film. Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii (1863-1944) was a man well ahead of his time. He developed an early technique for taking colour photographs involving a series of monochrome photographs and colour (R-G-B) filters. The images below show an example of Alim Khan, Emir of Bukhara. It is shown in comparison with two grayscale renditions of the photograph. The first is the lightness component from the Lab colour space, and the second is a grayscale image extracted from RGB using G=0.299R+0.587G+0.114B. Both offer a different perspective of how the colour in the image could be rendered by the camera. None present the vibrance of the image in the same way as the colour image.

Why bother with film photography?

About a year ago I decided to take a relook at film photography. After so many years taking digital photographs it seemed like an odd sort of move. My trip back to film began when I bought a Voigtländer 25mm lens for my Olympus MFT camera. It is completely manual, and at the moment I started focusing, I knew that I had been missing something with digital. Harking back to film seems a move that many amateur photographers have decided to make. Maybe it is a function of becoming a camera aficionado… the form and aesthetic appeal of vintage cameras brings something that modern digital cameras don’t – a sense of character. There is a reason some modern cameras are modelled on the appearance of vintage cameras. Here are some thoughts.

Digital has changed the way we photograph, and although we know we will never bungle a holiday snap, it does verge on clinical at times. I can take 1000 photographs on a 2-week trip, and I do enjoy having instant access to the photograph. Digital is convenient, no doubt about that, but there is some aesthetic appeal missing that algorithms just can not reproduce. Taking a digital image means that each pixel is basically created using an algorithm. Light in, pixel out. Giving an image a “film-look” means applying some form of algorithmic filter after the image is taken. Film on the other hand is more of an organic process, because of how the film is created. Film grains, i.e. silver crystals are not all created equal. Different films have different sized grains, and different colour profiles.

There are many elements of photography that are missing with digital. Yes, a digital camera can be used in manual mode, but it’s just not the same. For the average person, one thing missing with digital is an appreciation for the theory behind taking photographs – film speed (meaningless in digital), shutter speed, apertures. Some digital lenses allow a switch over to manual focusing, which opens the door to control over how much of a photograph is in focus – much more fun that auto-focus. Moving to pure analog means that you have to have an understanding of camera fundamentals, and film types.

What type of camera to experiment with? While digital cameras tend to have the same underpinning technology, film cameras can be quite different. A myriad of differing manufacturers, and film sizes. Do you want to use a box camera (aka Brownie), or a foldable one with bellows? A vintage German camera (East or West?), Japanese, or Russian? Full frame or half-frame? SLR or rangefinder? Zone focusing? Fully manual, or with light meter (assuming they work). So many choices.

Another part of the organic nature of film photography is the lenses. Unlike modern lenses which can be extremely complex, and exact, vintage lenses often contain a level of imperfections which means they provide a good amount of character. If you want good Bokeh, or differing colour renditions, then a vintage lens will provide that. They are manual, but that’s the point isn’t it? Lastly there is the film. Each film has it’s own character. Monochrome film to render cinematic ambiance, or colour film that desaturates colours. There are also films which have no (inexpensive) digital equivalent – like infrared film (from Rollei, and not really the same as using a filter).

Apart from pure analog, there is also the cross-over of analog to digital, the hybrid form of photography. This is achieved by using vintage analog lenses on digital cameras, providing the best of both worlds. It does mean that functions such as aperture control, and focusing have to be done manually (which isn’t a bad thing), but also allows for much more creative control. There are also effects such as Bokeh, which can not be reproduced algorithmically in any sort of organic manner.

There is some irony in film though. Many people of course end up digitizing the film. But the essence of the photograph is captured in the film and digitizing it does not take all of that away (it does loose something as the transferral from film to paper adds another layer of appeal). To display your work, digital is still the best way (hard to write a blog post with a paper photograph). My foray into film is partly a longing to relive the experiential side of photography, to play with apertures, to focus a lens – it doesn’t have to be exact, and that’s the point.

The downside is of course you will never get to see the photograph until after it is developed. However it’s best to look at this more from a more expressive point-of-view. The art may lie partially in the unveiling. Maybe film photography lends itself more to an art form.