Photographs sometimes contain blur. Sometimes the blur is so bad that it can’t be removed, no matter the algorithm. Algorithms can’t solve everything, even those based on physics. Photography ultimately exists because of the existence of glass lenses – you can’t make any sort of camera without them. Lenses have aberrations (although lenses these days are pretty flawless) – some of these can be dealt with in-situ using corrective algorithms.

Some of this blur is attributable to vibration – no one has hands *that* steady, and tripods aren’t always convenient. Image stabilization, or vibration reduction has done a great job in retaining image sharpness. This is especially important in low-light situations where the photograph may require a longer exposure. The rule of thumb is that a camera should not be hand-held at shutter speeds slower than the equivalent focal length of the lens. So a 200mm lens should not be handheld at speeds slower than 1/200 sec.

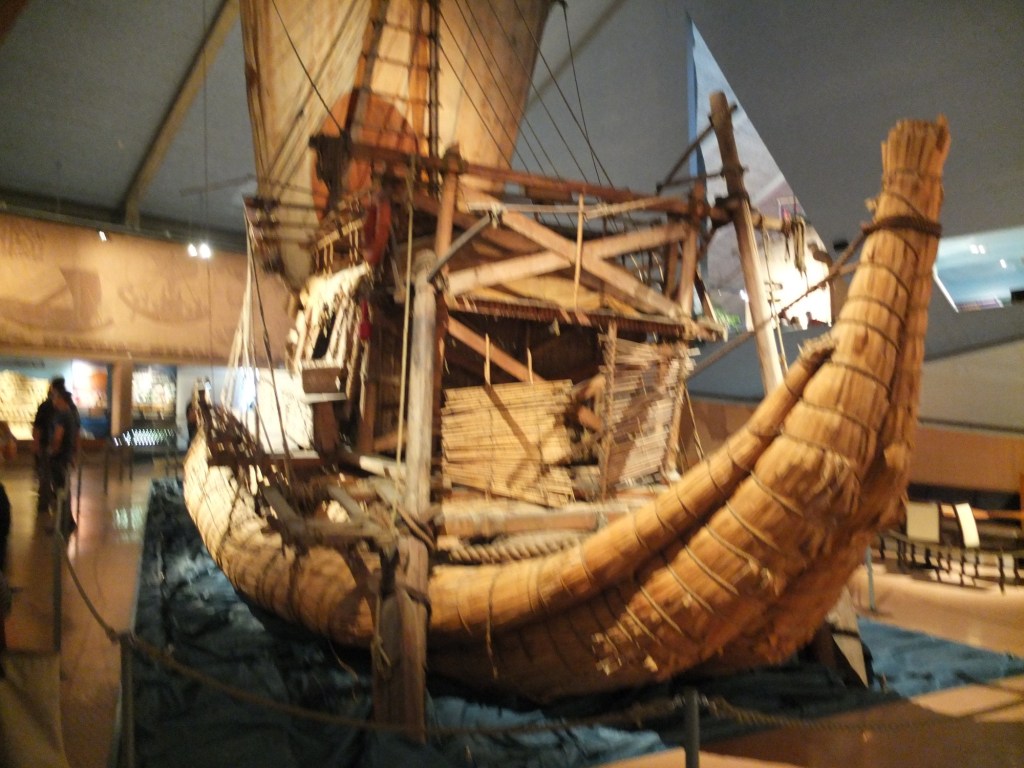

Sometimes though, the screen on a digital camera doesn’t tell the full story either. The resolution may be too small to appreciate the sharpness present in the image – and a small amount of blur can reduce the quality of an image. Here is a photograph taken in a low light situation, which, with the wrong settings, resulted in a longer exposure time, and some blur.

Another instance relates to close-up, or macro photography, where the depth-of-field can be quiet shallow. Here is an example of a close-up shot of the handle of a Norwegian mangle board. The central portion of the horse, near the saddle, is in focus, the parts to either side are not – and this form of blur is impossible to suppress. Ideally in order to have the entire handle in focus, one would have to use a technique known as focus stacking (available in some cameras).

Here is another example of a can where the writing at the top of the can is almost in focus, whereas the writing at the bottom is out-of-focus – due in part to the angle the shot was taken, and the shallow depth of field. It may be possible to sharpen the upper text, but reducing the blur at the bottom may be challenging.