Travel snaps have been around since the dawn of photography. Their film heyday was likely the 1950s-1970s when photographs taken using slide film were extremely popular. Of course in the days of film it was hard to know what your holiday snaps would look like until they were processed. The benefit of analog was of course that most cameras offered similar functionality, with the aesthetic provided by the type of film used. While there were many differing lenses available, most cameras came with a stock 50mm lens, and most people travelled with a 50mm lens, possibly a wider lens for landscapes, and later zoom lenses.

With digital photography things got easier, but only in the sense of being able to see what you photograph immediately. Modern photography is a two-edged sword. On one side there are a lot more choices, in both cameras, and lenses, and on the other side digital cameras have a lot more dependencies, e.g. memory cards, batteries etc., and aesthetic considerations, e.g. colour rendition. Below are some of myths associated with travel photography, in no particular order, taken from my own experiences travelling as an amateur photographer. I generally travel with one main camera, either an Olympus MFT, or Fuji X-series APS-C, and a secondary camera, which is now a Ricoh GR III.

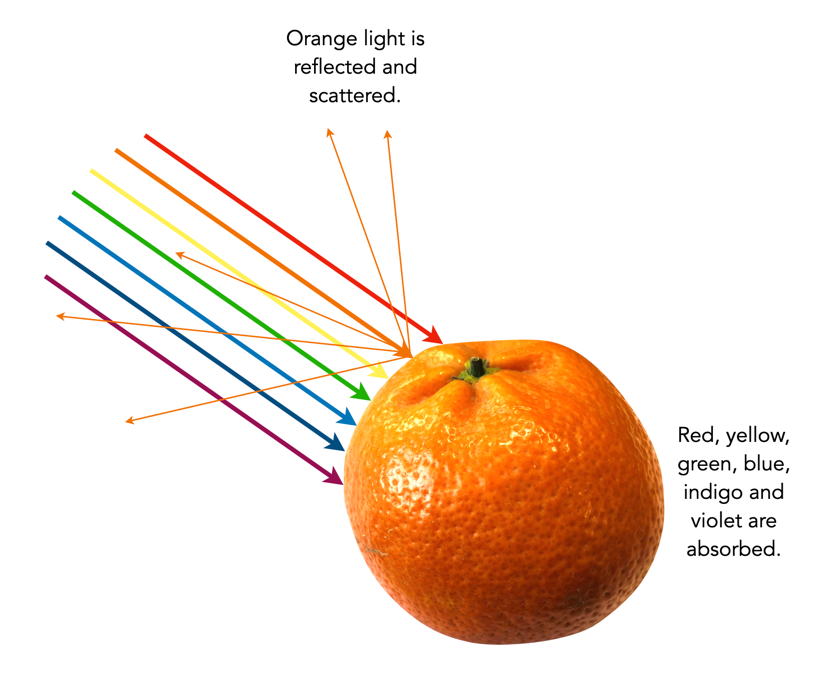

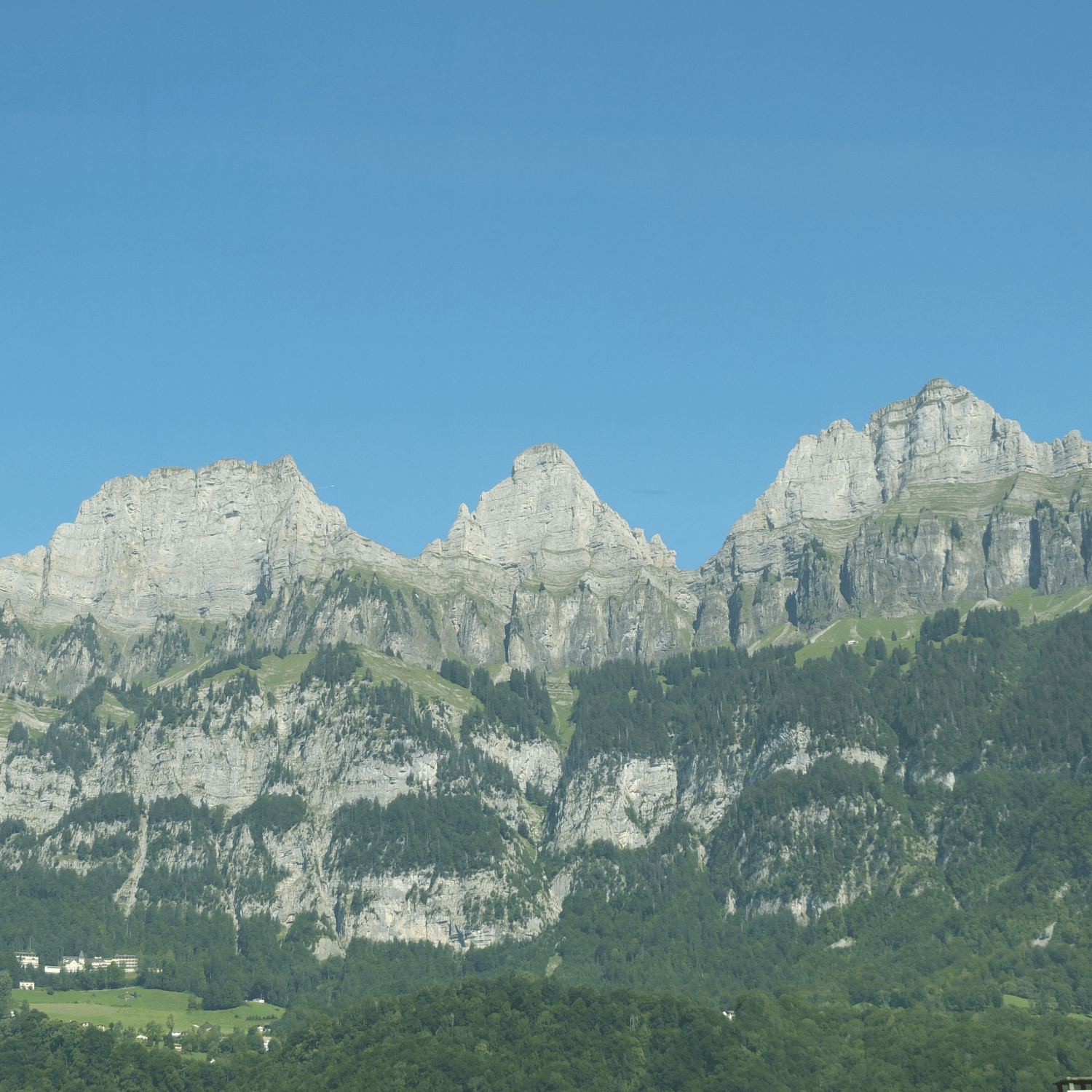

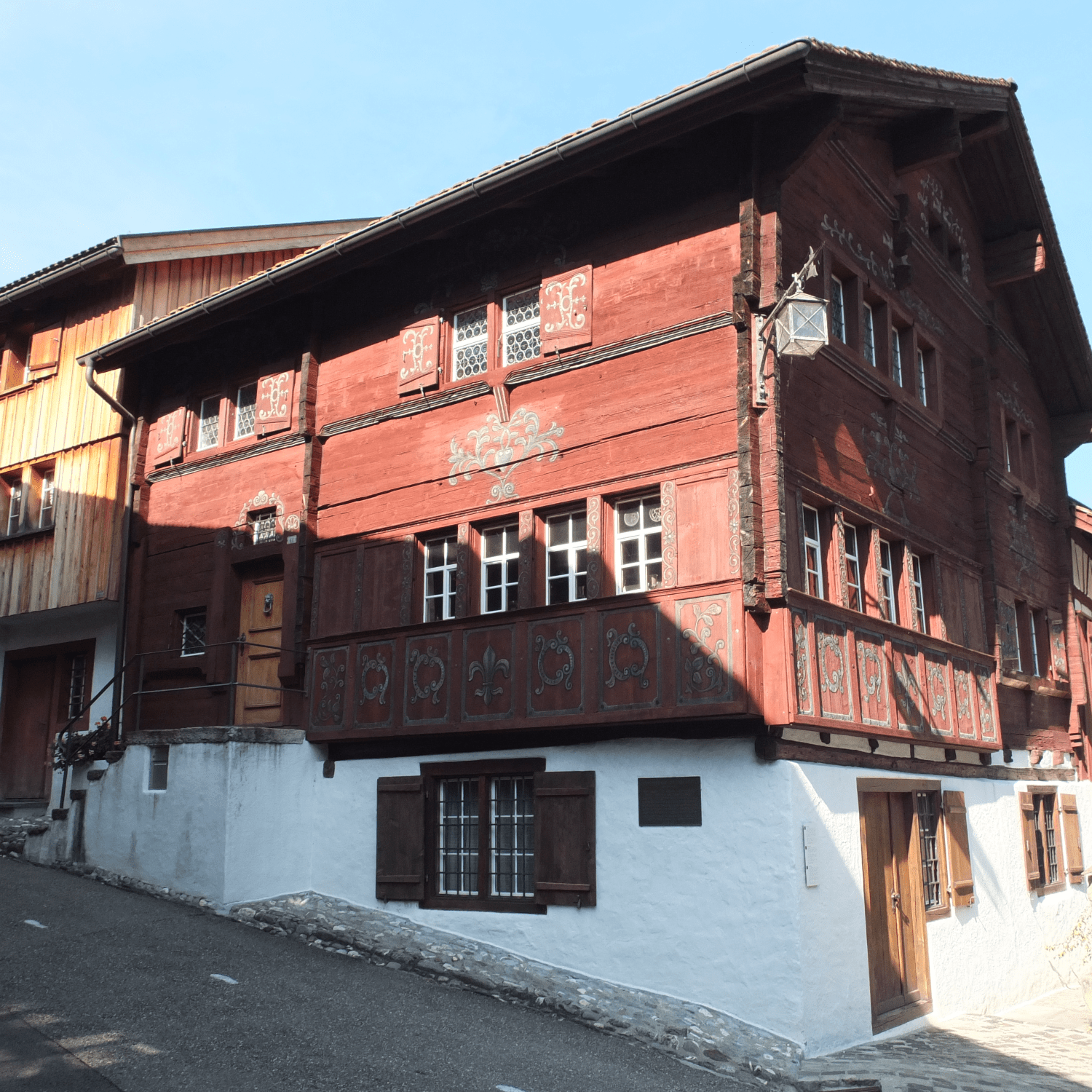

The photographs above illustrate three of the issues with travel photography – haze, hard shadows, and shooting photographs from a moving train.

MYTH 1: Sunny days are the best for taking photographs.

REALITY: A sunny or partially cloudy day is not always congenial to good outdoor photographs. It can produce a lot of glare, and scenes with hard shadows. On hot sunny days landscape shots can also suffer from haze. Direct sunlight in the middle of the day often produces the harshest of light. This can mean that shadows become extremely dark, and highlights become washed out. In reality you have to make the most of whatever lighting conditions you have available. There are a bunch of things to try when faced with midday light, such as using the “Sunny 16” rule, and using a neutral density (ND) filter.

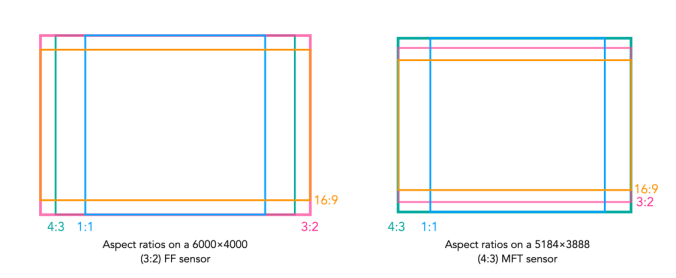

MYTH 2: Full-frame cameras are the best for taking travel photography

REALITY: Whenever I travel I always see people with full-frame (FF) cameras sporting *huge* lenses. I wonder if they are wildlife or sports photographers? In reality it’s not necessary to travel with a FF camera. They are much larger, and much heavy than APS-C or MFT systems. Although they produce exceptional photographs, I can’t imagine lugging a FF camera and accessories around for days at a time.

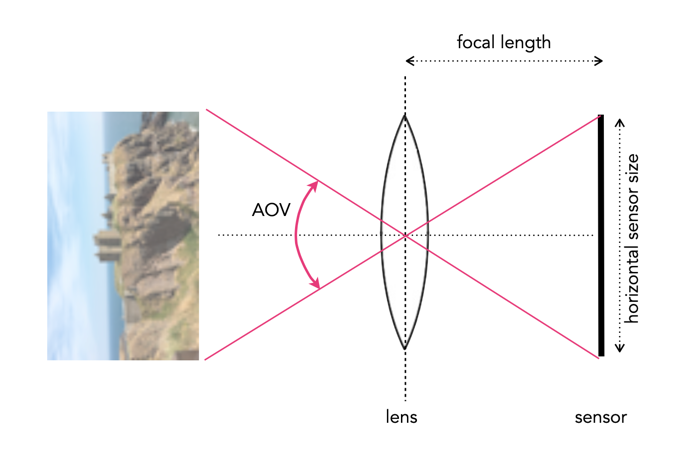

MYTH 3: It’s best to travel with a bunch of differing lenses.

REALITY: No. Pick the one or two lenses you know you are going to use. I travelled a couple of times with an extra super-wide, or telephoto lens in the pack, but the reality is that they were never used. Figure out what you plan to photograph, and pack accordingly. A quality zoom lens is always good because it provides the variability of differing focal lengths in one lens, however fixed focal length lenses often produce a better photograph. I would imagine a 50mm equivalent is a good place to start (25mm MFT, 35mm APS-C).

MYTH 4: The AUTO setting produces the best photographs.

REALITY: The AUTO setting does not guarantee a good photograph, and neither does M (manual). Ideally shooting in P (program) mode probably gives the most sense of flexibility. But there is nothing wrong with using AUTO, or even preset settings for particular circumstances.

MYTH 5: Train journeys are a great place to shoot photographs.

REALITY: Shooting photographs from a moving object, e.g. a train requires the use of S (shutter priority). You may not get good results from a mobile device, because they are not designed for that. Even using the right settings, photographs from a train may not always seem that great unless the scenery allows for a perspective shot, rather than just a linear shot out of the window, e.g. you are looking down into valleys etc. There is issues like glare, and dirty windows to contend with.

MYTH 6: A flash is a necessary piece of equipment.

REALITY: Not really for travelling. There are situations you could use it, like indoors, but usually indoor photos are in places like art galleries and museums who don’t take kindly to flash photography, and frankly it isn’t needed. If you have some basic knowledge it is easy to take indoor photographs with the light available. Even better this is where mobile devices tend to shine, as they often have exceptional low-light capabilities. Using a flash for landscapes is useless… but I have seen people do it.

MYTH 7: Mobile devices are the best for travel photography.

REALITY: While they are certainly compact and do produce some exceptional photographs, they are not always the best for travelling. Mobile devices with high-end optics excel at certain things, like taking inconspicuous photographs, or in low-light indoors etc. However to get the most optimal landscapes, a camera will always do a better job, mainly because it is easier to change settings, and the optics are clearly better.

MYTH 8: Shooting 1000 photographs a day is the best approach.

REALITY: Memory is cheap, so yes you could shoot 1000 frames a day, but is it the best approach? You may as well strap a Go-Pro to your head and video tape everything. At the end of a 10-day vacation you could have 10,000 photos, which is crazy. Try instead to limit yourself to 100-150 photos a day, which is like 3-4 36 exposure rolls of film. Some people suggest less, but then you might later regret not taking a photo. There is something about limiting the amount of photos you take and instead concentrate on taking creative shots.

MYTH 9: A tripod is essential.

REALITY: No, its not. They are cumbersome, and sometimes heavy, and the reality is that in some places, e.g. atop the Arc de Triomphe, you can’t use a tripod. Try walking around the whole day in a city like Zurich during the summer, lugging a bunch of camera gear, *and* a tripod. For a good compromise, consider packing a pocket tripod such as the Manfrotto PIXI. In reality cameras have such good stabilization these days that in most situations you don’t need a tripod.

MYTH 10: A better camera will take better pictures.

REALITY: Unlikely. I would love to have a Leica DLSR. Would it produce better photographs? Maybe, but the reality is that taking photographs is as much about the skill of the photographer than the quality of the camera. Contemporary cameras have so much technology in them, learn to understand it, and better your skills before thinking about upgrading a camera. There will always be new cameras, but it’s hard to warrant buying one.

MYTH 11: A single battery is fine.

REALITY: Never travel with less than two batteries. Cameras use a lot of juice, because features like image stabilization, and auto-focus aren’t free. I travel with at least 3 batteries for whatever camera I take. Mark them as A, B, and C, and use them in sequence. If the battery in the camera is C, then you know A and B need to be recharged, which can be done at night. There is nothing worse than running out of batteries half-way through the day.

MYTH 12: Post-processing will fix any photos.

REALITY: Not so, ever heard of the expression garbage-in, garbage-out? Some photographs are hard to fix, because not enough effort was taken when they were taken. If you take a photograph of a landscape with a hazy sky, it may be impossible to post-process it.